In September, UN Secretary-General António Guterres announced his system-wide strategy to achieve gender balance at all levels across the UN by 2028. The strategy aims to deliver on a long-standing – and long-neglected – UN commitment to achieve equal numbers of women and men in staffing. First made by the General Assembly in 1994, the initial deadline for parity was 2000, but without targets and penalties, progress was slow. Currently, 32% of senior managers are female, and 43.7% of staff at lower levels.

Calls for progress without accountability measures are a hallmark of UN reform efforts. Not this time. Guterres’s strategy comes with targets that are tailored to each UN entity according to the extent of its gender deficit. It details changes to recruitment processes and workplace conditions to help attract and retain women. Most importantly, there are measures to correct for failures. If a particular UN body fails to meet targets from mid-2018 onwards, appointments made by their leaders may be revoked and a central human resources department can intervene to correct for gender biases in recruitment and promotion.

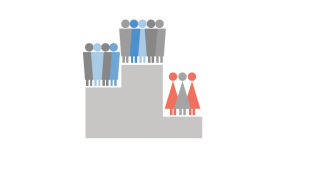

On the surface, the UN does not appear out of step with comparable organisations when it comes to women’s share of positions. But the averages disguise the paucity of women in the UN’s power centres. Women are concentrated at lower levels of the seniority hierarchy. As of December 2015, they dominated the lowest professional category (P2) at 57.5%, and were scarce at the highest, with just 27.3% of Under-Secretaries-General.

In specific sectors, such as humanitarian support and peace operations, women make up just 28% of all international staff, compared to 44% across the whole UN. The gender gap is most stark in UN peace operations, where it would take 703 years at current rates to reach parity at senior director level.

Gender parity alone cannot improve delivery of the UN’s many commitments to advancing gender equality and women’s rights. The creation of UN Women in 2010 has been the most significant step in that direction, and it should be supported as the policy leader on women’s empowerment and gender equality. But having more women across the UN’s leadership will support that agenda, especially if it is signalled from the top that a commitment to gender equality is expected from all staff, at all levels.

Photo: Mark Garten. Copyright UN Photo