In April this year, I was appointed by Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson to be the first UK Special Envoy for Gender Equality. It’s a role that demonstrates how much of a priority this is for the UK Government. The Foreign Secretary has made it clear that he wants to see a foreign policy that “consciously and consistently delivers for women and girls” around the world. The Department for International Development has mainstreamed gender equality throughout its work. The Ministry of Defence provides gender awareness training to our own forces and those of other countries, including peacekeepers in conflict zones. The Government Equalities Office oversees our domestic legislation and practice relating to equality, LGBT issues and the gender pay gap. This really is a cross-Government undertaking.

In many respects and in many circles, the debate has begun to shift from ‘why’ should we aspire to gender equality in all that we do, to ‘how’ can we better ensure gender equality is hardwired throughout our work. But there is still work to be done to help change hearts and minds. We must set out the rationale for the achievement of gender equality.

The legal, moral and social case is clear. Gender equality is enshrined in international law. Women and girls face disproportionate threats during conflict. They are less likely to be able to go to school. Very often, they are less able to exercise control over their lives and their health. Women’s voices are heard less often and their opinions are less often taken into account. And – shockingly – one in three women will experience violence at some point in her lifetime.

But there is a very strong economic and political case too. More equal societies tend to be more prosperous. When more women work, economies grow. According to a 2015 report by the McKinsey Global Institute, a private sector think tank, a huge $12–28 trillion could be added to the global economy if women played a part equal or equivalent to men. And yet, the World Economic Forum predicts that it could take over 217 years to reach economic parity.

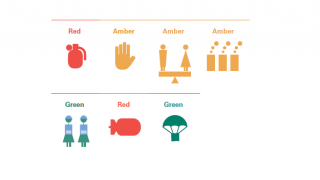

Gender inequality takes a very different form in different countries. What’s right in one region might not work in another region. So we have crafted a three-pillar policy – Equal, Empowered and Safe – that enables each mission in our global diplomatic network to respond in a way that works for their context.

But we cannot do this alone. Our new National Action Plan on women, peace and security, to be launched in January 2018, will set out seven strategic outcomes contributing to the four pillars of the women, peace and security agenda – participation, protection, prevention, and relief and recovery – to be achieved by working in partnership with the UN and others.

The role and function of the UN is vital if we are to get the high-level political leadership and commitments to make a difference. So, for example, when former Foreign Secretary Lord Hague made preventing sexual violence in conflict (PSVI) a priority, he worked closely with UN Special Envoy for Refugees Angelina Jolie to co-host the first and largest conference of its kind to firmly place PSVI on the world’s agenda.

We know that sexual violence against women and men, girls and boys, still takes place too often. Lives and livelihoods are destroyed; communities are fractured and stigma is rife. We are working hard to address the causes and impacts of sexual violence wherever it happens. Our Special Representative for the Prevention of Sexual Violence in Conflict – Lord Ahmad – launched the Global Principles for Action against Stigma at this year’s opening of the UN General Assembly, alongside the UN’s Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Pramila Patten.

We also want to see more women playing a substantive role in peace settlements, as this means the chances of reaching agreement are 50 per cent greater, and agreements are 35 per cent more likely to last for at least 15 years. That’s why we are making it a priority to identify and support more women mediators, and are hosting a conference in Wilton Park this month to build knowledge and capacity.

We’ve made it a priority to eradicate sexual exploitation and abuse, and to ensure that peacekeeping operations provide the highest levels of protection for women and girls in conflict areas. If they cannot trust the peacekeepers, who can they trust?

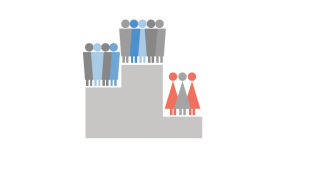

And we keenly support the UN Secretary-General’s mission to see gender parity in the United Nations and more women across the different sectors. Collectively, we need to ensure that the roles and experiences of women are included in our global policy and operational responses.

It may be a neat headline but there’s truth when we write that this isn’t just the right thing to do; it’s the smart thing to do.

Photo: Joanna Roper meeting school girls in Pakistan – 2017 © UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office