“As millions of children, women and men spill out of their countries towards safety, they find themselves at the mercy of merciless people” – Secretary-General Antonio Guterres

The global nature of human trafficking causes serious violations of international human rights. Today at least an estimated 21 million people, including 5 million children, are trafficked. While the abolition of slavery and forced labour was one of the first human rights struggles in modern history, it is clear that the international community can and must do more to protect the most vulnerable globally from being abused by traffickers.

As one of the issues directly mentioned in the Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 5 on gender equality, Goal 6 on clean water and sanitation and Goal 16 on promoting peaceful and inclusive societies), the issue of human trafficking causes significant issues to most member states. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) defines human trafficking as “the acquisition of people by improper means such as force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them.” With the addition of human trafficking to the agenda of the Security Council in December 2016, the Council noted that human trafficking not only violates basic human rights, but also propagates instability in conflict regions. Terrorist organisations like ISIL (Da’esh) and Boko Haram target minorities and use these acts to promote religious justifications to support institutionalised sexual slavery.

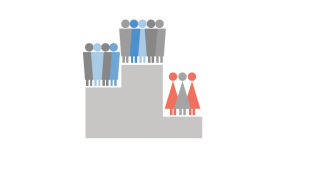

While the causes and impacts of human trafficking vary from country to country, generally the most vulnerable in society are targeted, which often include women and children. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that 22 per cent of victims are sexually exploited. The ILO also reported that the Asia-Pacific region accounts for most people in forced labour with almost 12 million, or 56 per cent of the global total. While international efforts to tackle human trafficking have resulted in more member states criminalising this activity, conviction rates and potential solutions remain low. Member states adopted in 1949 the United Nations Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others, the first international agreement on human trafficking. Unfortunately only 82 member states are parties to the treaty with a further 25 having signed but not ratified.

The international nature of human trafficking requires member states to collaborate. With over 500 different trafficking flows detected in Western and Southern Europe alone and with victims of 137 different nationalities - as reported by UNODC in their 2016 Global Report on human trafficking - it is clear that traffickers are able to profit from the most vulnerable in society. Estimated profits from human trafficking were over $150 billion in 2014, according to the ILO.

The question of how member states should deal with human trafficking is multi-faced. While most member states have legislation which criminalises human trafficking, in reality, very few human traffickers face prosecution due to issues of corruption and the difficulty in prosecuting the perpetrators.

Differing approaches have led to differences between member states in their solutions towards human trafficking, resulting in a split international community. For example, Scandinavian countries like Sweden have seen a decrease in sex trafficking due to the legalisation of selling sex and the criminalisation of the purchasing of sex. Since 1995, this change in law has meant that from Sweden’s point of view, any woman who is selling sex has been forced to do so, either by circumstance or coercion. As a consequence, anybody who is caught buying sex faces numerous sanctions: from fines to time in prison. According to the Swedish Ministry of Justice, over 70 per cent of Swedes support this law. While Sweden’s neighbours first looked at the idea sceptically, statistics from a 2012 paper from the World Development journal stated that street prostitution decreased by between 30-50 per cent after the implementation of this law. Further stating that countries “with legalised prostitution have a statistically significantly larger reported incidence of human trafficking inflows.”

However, the implementation of laws as seen in Sweden is seldom replicated globally. In Ethiopia for example, the consequences of human trafficking are looked at instead of the root causes. The US State Department have established a set of minimum standards against human trafficking. While in 2016 the Ethiopian government promoted a media campaign which reached hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians on the risks posed by human trafficking, Ethiopia still did not appear to meet those standards. Particularly, it has not dealt with issues like internal trafficking and it has remained without procedures for front-line responders. While Ethiopia has focused on the transnational nature of human trafficking, it has failed to prosecute sex traffickers and internal forced labour cases.

These differing approaches between member states have led to a failure of implementation. While UNODC notes that there is a solid legislative process, there are still very few convictions. While resolution 2331 of the Security Council condemned human trafficking, the reality is, according to the Director-General of UNODC Yury Fedotov, that “what we need is more meaningful international cooperation and adequate funding to take effective action. Otherwise, our efforts to stop this terrible crime, which hinders development and so unscrupulously profits from the despair and vulnerability of people everywhere, can only fall short”.

In conclusion, unless governments collaborate in finding and convicting the perpetrators of human trafficking, any potential solutions will fall short in protecting the most vulnerable in society from forced labour and sexual abuse.

Photo: A young visitor to the Palais des Nations in Geneva adds her name to a symbolic signature panel in support of the “50 for Freedom” campaign to end modern slavery. UN Photo/Jean-Marc Ferré