As a policy to combat sexual exploitation and abuse, zero tolerance seems obvious.

Tolerance in any form – active, passive or unintentional – can normalise inappropriate behaviour and create a toxic environment in which violent transgressions are more likely, and more likely to be suppressed or ignored. Even minor actions can have damaging effects when they are part of wider patterns and structures of abuse and inequality.

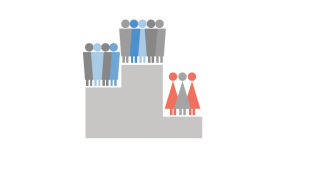

This will not come as a surprise to most women. Global estimates published by the World Health Organization indicate that over a third of all women – 35 per cent – have experienced either physical or sexual violence, most at the hands of their husband, boyfriend or male family member. Even allowing for serial or repeat abusers, that’s still a lot of men. Clearly, this will not be news to them either.

In most sectors, just one case can ruin an organisation’s reputation, although it seems to have taken the avalanche of allegations against prominent figures in Hollywood and US and UK politics for these industries to wake up.

The UN, on the other hand, has been grappling publicly with sexual exploitation and abuse for some time, most prominently in its peace operations. It first set out a zero-tolerance approach in 2003. This was reinforced in a 2005 report by Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, then Jordanian Ambassador to the UN, now UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

So what’s the problem with zero tolerance? Surely it’s the best way to stop abuse?

Well, there are three strands of criticism. The first relates to definitions. The UN defines sexual exploitation as “… abuse of position of vulnerability, differential power or trust, for sexual purposes…” and sexual abuse as “… physical intrusion of a sexual nature, whether by force or under unequal or coercive conditions”.

Notions of propriety are inherently cultural. In our patriarchal society, all inter-gender relations are arguably unequal; indeed, all relationships have power dynamics. Critics therefore contend that the UN, with its unique ability to create international norms, could do more to set baseline standards and establish what is never appropriate.

Second, many practitioners find the policy impractical. They argue that it has been interpreted to mean that any sexual relationship between UN staff and nationals of the host country is abusive, with the rather Victorian exception of relationships within marriage.

As a consequence, significant amounts of effort are expended determining the propriety of relationships. This can be particularly time consuming when the UN has large numbers of peacekeepers from country X stationed a few miles across the border in country Y, leading to the policing of an ill-defined border. It can also feel uncomfortably akin to judging relationships on the basis of nationality. Many feel that these resources could be better deployed tackling clear-cut cases of abuse.

Finally, there are concerns that zero tolerance fails to place enough emphasis on the importance of consent and the particular atrociousness of rape. A false equivalence might be drawn between crimes of non-consent and still serious but non-criminal professional misconduct. Some UN personnel and troops may even form the impression that all sexual acts, consensual or not, are not permissible while deployed with the UN but are acceptable at other times. Some troops have responded to investigators: “Why did you give us condoms if this is not allowed?” And consent itself is a thorny issue, not always easy to determine, not always freely given.

At the same time, the UN rightly feels that it must make clear that sexual impropriety in any form will not be tolerated. It does not want to trivialise victims’ experiences or contribute to a dangerous, enabling atmosphere. While concerns about zero tolerance are frequently raised in private, few practitioners are willing to do so publicly.

What is the solution? In part it will come from listening more closely to victims, and bringing a victim perspective into this discussion. The Secretary- General’s appointment of Jane Connors as the first UN Victims’ Rights Advocate is an important step forward in this regard.

UNA-UK believes that accountability must also be part of the equation. However one feels about zero tolerance, it is ultimately a human resources policy and no substitute for the criminal prosecution of criminal acts.

Prosecutions must be sought for all cases involving allegations of recognised sexual crimes. When no such crimes are involved, the policy must kick in with real consequences.

Seeking prosecution for acts of sexual violence is important because it punctures the climate of impunity that enables perpetrators. It is also important because it places a gradient of severity on top of the otherwise flat policy that the zero-tolerance approach risks creating. Most important of all, it can provide survivors with a sense of justice.

To find out more about UNA-UK’s work on this issue, visit www.mission-justice.org

Photo: Martine Perret. Copyright UN Photo