A recent story, while largely travelling under the radar, might just have prompted a few raised eyebrows. A British trans woman, it was reported, has just been granted asylum in New Zealand on the grounds that it is safer for her to live there than in the UK.

This comes little more than a year after a change in advice dished out to travellers by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, to the effect that LGBT travellers should now treat the United States – particularly the more isolated rural and southern states – with added caution.

For those with a proudly Anglocentric view of the world this may be something of a shock. We do things so much better, don't we? Both the UK and the US once led the world in promoting LGBT rights. How has it come to this, that trans people are now contemplating a life elsewhere from what were once considered safe havens?

The answer lies, in part, in an understanding of transfeminism, which has been around since at least the 1960s, and the ways in which that relates to and interacts with traditional feminisms. At one level, transfeminism is no more than trans-flavoured feminism. Trans women face many of the same oppressions as women and for much the same reasons – although transfeminism is not limited to trans women.

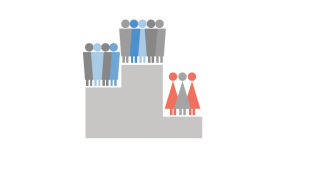

Transfeminism provides insights into feminism that are broadly informed by trans politics. For, while the experience of trans women differs from that of cisgender (non-trans) women in many ways, trans women (and men) also provide a unique perspective on gender difference. For, having lived on both sides of the gender fence, they alone have direct personal insight into how society differentiates – and discriminates between - men and women.

Transfeminism is not without its critics - enemies even - within the body of feminism. The wide and diverse experience of trans people means that transfeminists are naturally drawn to “Third Wave Feminism”, and its espousal of intersectionality. This maintains that the oppression of individuals is not universally identical, but is mediated by social attitudes towards factors such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and possession of disability.

As such, transfeminism is frequently opposed by elements of “Second Wave Feminism”, with its equally strong belief in “sisterhood” and the universality of women's experiences. Many of this generation argue that trans women can never be accepted as women and, in some cases, support the eradication of trans people altogether.

How does this relate to the anti-trans backlash in two states formerly considered to be safe? And what are the implications of that for the wider world – and UN policy within it?

It starts with a given, that certain religious groupings harbour strong anti-trans prejudice. Prejudice is not specific to any one religion, rather, it is a feature of the more fundamentalist branches of all. Those who subscribe to the essentialist view that “God made the world just so” will be more inclined to believe that any deviation from the natural order is sacrilege and – also a feature of fundamentalism – that “deviants” deserve to be punished severely.

As such, there is a sort of unofficial fellowship in faith that joins the adherents of anti-LGBT laws and second-class citizenship for women in parts of the Middle East with those supporting similar initiatives in North America. Elsewhere, research suggests that for the first time, European fundamentalist Christians are becoming a force equivalent to their American cousins.

In the US, insofar as it is possible for someone writing from the UK to tell, the impact of this backlash is softened by the emergence of a broad coalition of women and LGBT folk determined to “persist”. Not all is plain sailing, but it does feel as though a broad fightback coalition is emerging, and that possibly reflects a reaction to the rightward lurch of US politics more generally.

In the UK, the situation is different. Here, an outwardly right-wing government remains committed to standing firm for LGBT rights: even extending trans rights in several significant ways. Anti-trans attacks – and they are ferocious – come from an unlikely alliance of Second Wave Feminists and the right-leaning media. It's complicated.

The UN must therefore tread cautiously. A broad commitment to LGBT rights is good. But seeing how anti-trans attacks play out differently in different places, too detailed a prescription could as easily lend weight to the transphobes as undermine them. In both UK and US, transphobes are as likely to be galvanised by what they see as UN interference as shamed by it.

In Russia, rejecting soft western liberalism – and LGBT rights – serves as rallying point for government, which frequently positions itself as fighting back against western cultural interference.

The UN needs to set out basic values, including a commitment to the Human Rights of all in respect of sexual orientation and gender identity. It helps, too, when the UN backs official investigation of violence against people targeted for these characteristics, as it did in 2016.

But, softly, softly: it will achieve more working with local LGBT organisations; much more if it is prepared to be led, rather than lead. In the final analysis, it must respect local politics, and not impose values.

Go slow: go with the flow. It may be the less exciting road, but in the end, it is the only practical road to success.

Photo Credit: UN/Wikimedia via creative comms