The recent proliferation of feminist foreign policies is linked to the emergence and consolidation of the women, peace and security agenda in the United Nations over the last 17 years. The same revolutionary impulse that seeks to make feminism the defining guide of a country’s foreign policy had already put gender equality on the agenda of the Security Council, and given prominence and visibility to a growing field in international policymaking. The principles animating today’s feminist foreign policies overlap with the core tenets of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda since the adoption of Security Council resolution 1325 in 2000, recognising the importance of women’s role in conflict prevention and resolution.

Advancing this agenda is one of the main pillars of the work of UN Women, established in 2010 out of the merger of four smaller UN entities working on gender equality and the empowerment of women, and with a mandate to lead the UN’s efforts on Women, Peace and Security. In that span of time, UN Women has been at the centre of many of the efforts that have made a difference in the world of international cooperation and diplomacy.

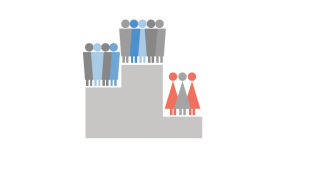

As recently as a decade ago, many atrocities committed against women and girls in conflict situations were barely reported. The absence of women from peace negotiations was commonplace and accepted as normal. International jurisprudence on conflict-related sexual violence had only just begun to take shape with the first landmark convictions in international courts, and few survivors of such atrocities had received any reparations or assistance. By the end of 2007, only seven countries, all of them European and including the United Kingdom, had adopted national plans of action on Women, Peace and Security. Since then, the number of such countries has grown to 71, foreign aid’s investment in gender equality has quadrupled, and the United Nations is now devoting more time, attention and resources to conflict-related violence against women than ever before.

Most peace negotiations are still male-dominated affairs, but there are many more journalists that notice and report it when it happens, many more academics proving the difference that it makes to the likelihood of reaching a peace agreement and its durability, and many more mediators trained on the norms emanating from 1325 and how to put them into practice: meeting regularly with women’s organisations, insisting on the presence of women and gender experts in their teams and among the parties to the talks, and ensuring that a wide range of gender equality issues are put on the agenda and reflected in the peace agreement.

Over the last year, several groupings of countries, from the Commonwealth and the Mediterranean to the Nordic countries and Africa, have put together rosters of women mediators, hopefully putting to rest the fallacy that the reason only men are asked to mediate peace talks is a shortage of qualified women. For example, Colombian women played a much-celebrated role in one of the most brilliant exercises in peacemaking in recent times, and UN Women had the privilege of supporting their efforts every step of the way. As a result, up to one-third of the negotiators at the table at the Colombian peace talks in Havana, half of the thousands of citizens consulted in regional and national forums in Colombia and a majority of the victims and experts that travelled to Havana to speak to both parties, were women. The peace agreement has more than one-hundred provisions on gender equality and, for the first time ever, UN Women was written into the agreement itself as an international guarantor.

Similarly, atrocities against women and girls in armed conflict have not abated, but after a long history of silence they are now far more likely to be reported on and investigated. UN Women, together with Justice Rapid Response, an organization that deploys international professionals in this field, have the largest and most diverse roster of experts in international investigations of gender-based crimes in the world, with 217 experts from 73 different countries and speaking 42 different languages. Since 2009, this roster has been used for 70 deployments to help document or prosecute crimes against women and girls in all corners of the world, from South Sudan to Syria to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

An important component of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda has been ensuring that a greater share of recovery and peacebuilding funds is invested on advancing gender equality, and the 15-percent earmark we have used for that purpose since 2010 has become a standard that is widely emulated. But we would have more impact if we were able to channel more resources to women’s civil society organisations in countries affected by conflict and humanitarian crises, and that is why we have set up the Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund.

Finally, at a time when preventing and countering violent extremism concentrates so much attention, UN Women has expanded its work in this area with more than 25 projects across the globe. We put women’s rights at the centre of these efforts: from prevention and countering radicalization, to counter-terrorism, to rehabilitation, reintegration and support for victims.

These are just some examples of UN Women’s work. They are part of a much bigger movement that aspires to be a dominant force in global affairs in the 21st century; new generations of feminist foreign policies will play a big part in that story.

Photo: Rick Bajornas. Signing Ceremony of Colombian Peace Agreement, Cartagen. Copyright UN Photo.