A grandfather says to his grandchild:

“There is a battle between two wolves inside me. One is evil; he is arrogance, ego, lies and despair. The other is good; he is peace, compassion, truth and hope. This battle is inside us all.”

Sweden’s new foreign policy is both unique and forward-thinking, but not surprising for a country that has a long tradition of aspiring towards a more equitable society at home. In fact, their egalitarian nature is reflected in this new feminist foreign policy (FFP), which demands “the fostering of women’s and girl’s rights” implemented within “its national commitments to human rights everywhere”, and which prioritizes “diplomacy over military responses.”

As across northern Europe, women’s rights emerged early in Sweden. Reforming gender relations was first debated in the 1930s. Encouraging women into the labour force through an individualised taxation system and 8-month paid parental leave (later expanded to 15 months) was introduced in the 1960s and ‘70s. Additional gender equality laws were introduced in the 1980s and ‘90s to allow women to combine work and child care, resulting in female employment rates that have been one of the highest in the Western world since the 1970s.

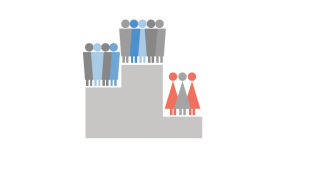

This is seen as the first phase of Sweden’s gender revolution. The second phase, starting in the 1990s further improved gender relations by putting a focus also on the role of fathers, by granting longer non-transferable paternal leaves and shared responsibilities between men and women as dual-carers and dual-earners. As a result, Sweden was considered the most gender-equal country in the EU between 2005-2015 (according to EIGE’s Gender Equality Index) and to this day ranks 4th as the most-gender equal country in the world (according to the Gender Gap Report 2016). Consequently “75% of young Swedish men hold egalitarian attitudes towards gender equality” and the current government of Sweden (even with a male Prime Minister) defines itself as a feminist coalition. Sweden’s long history of improving gender equality at home is seemingly the foundation stone of its new FFP.

The introduction of Sweden’s FFP has earned much praise, and yet the execution of feminist foreign policy, in particular in relation to Saudi Arabia has been challenging. The decision to discontinue the arms trade with a country which subjugates woman unleashed massive criticism both from Saudi Arabia and from other member states of the Arab-League, who called Swedish Foreign Minister Margot Wallström “irresponsible and unacceptable”.

A great deal of resentment was even voiced from within Sweden; primarily by companies who had stakes in Sweden’s large arms export business. With sales worth £275 million at stake, this was to be expected, but even companies such as H&M and Volvo who don’t sell arms complained, demonstrating how instrumental arms exports are to the Swedish economy. Still, the Swedish government regarded the sale of weapons to a country violating human rights as a moral issue and so £900 million worth of bilateral arms agreements with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were cancelled.

Aside from their actions in Yemen – where over 10,000 have lost their lives - Saudi-Arabia’s human rights abuses are exasperating: women being deprived of their basic rights, discrimination against Shia Muslims, detaining and imprisoning critics on “vaguely worded charges” and executions: since 1985 more than 2000 people have been executed. Torture is a common part of the judicial system, where courts accept forced “confessions” to condemn defendants in bogus trials. According to Amnesty International, Saudi’s death penalty “is so far removed from any kind of legal parameters that it’s almost hard to believe.”

Wallström’s public criticism of Saudi-Arabia’s treatment of women and the punishment of journalist Raef Badawi, which she described as “medieval”, are well known. Lesser known however, is the rapprochement between Saudi-Arabia and Sweden and the long-term impact (or lack thereof) on their relations; there is little evidence that “the incidence [outlined above] had any long-term consequences other than a decline in military trade”.

Nonetheless, many countries have failed to follow in Sweden’s footsteps. Britain’s attitude of appeasement towards Riyadh is one such example. Human rights (and women’s rights) abuses are only quietly discussed. Dating back to 1915, Britain’s relationship with Saudi Arabia is now worth billions, with “joint ventures between UK and Saudi companies worth £17.5bn”. Only recently, a Number 10 spokeswoman said the prime minister would mention Saudi Arabia’s human rights record when speaking to her counterparts, but securing arms deals were “vitally important (to sustain jobs in Britain),”. Former Defence Minister Michael Fallon went even further, urging MPs to stop criticising Saudi Arabia, in order to secure a fighter jet deal.

Given Britain’s current stance towards Saudi Arabia it seems like there is a long way to go before Britain views gender equality in Swedish terms. But reform can and should start closer to home. Nordic countries view family policy as, “one of the strategic priorities to achieving gender equality”. Some attempts have been made to strengthen women’s rights in Britain, such as allowing shared parental leave (for up to 11months altogether), but according to recent statistics from European Convention of Human Rights 54,000 women a year still lose their jobs due to maternity discrimination. Further, the costs of child care in the UK are so high, it is difficult to combine both caring and working (compared to Sweden, where child care is guaranteed to be never more than 3% of a family’s gross income, and capped at £113 a month). If Britain is to engender a sense of women’s rights throughout society like Sweden, it needs to start making changes within its family laws.

In a world where weapon sales are prioritised over human rights and gender equality, a “progressive, unambiguously pro-equality vision on foreign policy” is needed. Sweden can offer a blueprint, sowing the seeds of gender equality, but it is on us, and other nations, to nourish the willingness to enforce equality and solidarity for it to grow beyond borders.

The grandchild asks: “Which wolf wins?” The grandfather replies: “The one you feed.“

Photo: Secretary-General António Guterres (foreground right) meets with Margot Wallström (left), Minister for Foreign Affairs of Sweden. UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe