A few days before Donald Trump’s inauguration, my daughter was born at St Mary’s Hospital in London, surrounded by caring professionals and all the medical equipment we could possibly need.

As she slept next to me, I thought about the Tamil woman who saw a roadside, preterm caesarean as the safest course of action as she fled indiscriminate shelling and atrocity crimes – as yet unpunished – during the final stages of Sri Lanka’s civil war. I thought about the Yemeni child bride who reportedly died from vaginal injuries on her wedding night, and the woman in Florida, now a minimum-marriage-age campaigner, who was forced to marry her rapist when she was just 11.

I thought about the fact that one in three women will experience physical or sexual violence (and yes, #metoo); that around half of women in the EU have suffered harassment; that 71 per cent of trafficking victims are female; and that at least 200 million girls have been subjected to female genital mutilation, most before the age of five.

My little girl is lucky not to be born in a conflict zone, or into poverty. But her relative privilege cannot insulate her against the drawbacks of being female in 2017. Economically, politically and socially there are few areas where women have it as good as men: from the gender pay gap to the legal barriers that restrict their rights in many countries, the physical threats they face in their own homes, and the online abuse they experience for voicing opinions.

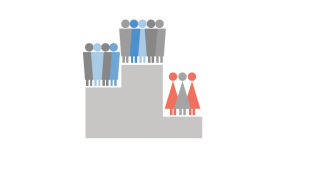

Even when women do well, it is often not enough to overcome the broader context of discrimination. Research by the universities of Glasgow and Missouri indicates that girls outperform boys in mathematics and reading in 70 per cent of countries. But this advantage evaporates when they leave school. Just half of working-age women are in the labour force, compared to 77 per cent of men. They are also more likely to be in low- or unwaged jobs. And over 130 million girls aren’t in school at all.

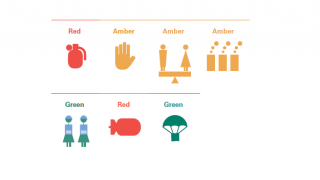

There is no shortage of shocking statistics. Some are included on page 5, because we need to keep reminding ourselves that we are not even close to gender equality. Throw colour, poverty, disability, non-binary identity or another such factor into the mix and the figures are even worse.

We also need to concentrate on the flip side: if the number of women raped is high, the number of men doing the raping must be pretty high too, repeat offenders notwithstanding. Whenever women face discrimination, there are men – and women – who bear individual and collective responsibility. If you aren’t challenging the status quo, that includes you.

It’s both depressing and uplifting to think that despite all this, it’s the best time in history to be a woman. When the UN was founded in 1945, women had equal voting rights in just 30 countries. Today, only one UN member state – Saudi Arabia – does not have universal suffrage. Many more girls are in school, maternal mortality has declined and there are fewer child marriages. Worldwide, the average proportion of women in parliament has nearly doubled over the past 20 years, and almost all countries have ratified the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (the US is a notable exception). We have come a long way, but not nearly far enough; for every step forward, there has been a backlash.

So what’s the answer? Spogmay Ahmed (page 13) and Anne Marie Goetz (page 15) look at feminism at the UN, and the impact that changes to its staffing and policies could have on the wider world. In our interview (pages 16–17), Diane Corner provides an example of progress at the sharpest end of the scale: sexual abuse by UN peacekeepers. But as Goetz says, internal changes alone “cannot improve delivery of the UN’s many commitments to advancing gender equality”.

Are feminist foreign policies the solution? In part, yes. On pages 6–8, Margot Wallström, Janice Charette and Joanna Roper make a compelling case for policies that protect, include, equip and empower women. They note that this approach is as much common sense as it is feminist. After all, enabling women to contribute trillions to the global economy and to craft durable peace agreements supports the traditional foreign policy goals of prosperity and security.

But as Zarina Khan argues on page 9, gender inequality is embedded in our political and economic systems. Governments are unlikely to overhaul themselves. And while every country has feminists fighting for equality (see pages 10–11), seeking to ‘export’ feminism is fraught with difficulty.

Empowering women is only half the job. Several studies (see, for example, Elin Bjarnegård and Erik Melander’s ‘Pacific Men: how the feminist gap explains hostility’) have shown what is self-evident: women are not automatically more tolerant, peaceful or feminist than men. Attitudes matter. Women – and men – who feel positive about gender equality are less likely to be intolerant towards religions or to view other countries as enemies.

This is where civil society comes in. Justine Masika Bihamba writes powerfully on page 22 about the need to fund frontline groups who know what is needed to bring about peace. Her words apply to feminism and human rights too. It is by supporting local efforts and actors that governments will achieve progress, in their own countries and abroad.

Photo: A woman leads the ‘Not in my name’ march in Pretoria, South Africa, following a spike in reports of women being murdered and raped, May 2017 © WIKUS DE WET/AFP/Getty Images