“A feminist is simply someone who believes that women should have equal rights to men.” If we accept this popular and generally uncontroversial notion of feminism then the premise of a feminist foreign policy, implemented by a feminist government, should be just as straightforward.

Evidently not. Most countries, including the UK, that profess to champion women’s rights do not have a feminist foreign policy. This is because feminism is fuller and more nuanced than the simple definition touted in mainstream culture.

The writer and civil rights activist Audre Lorde said: “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” Her feminism requires not only understanding the causes of inequality and the systems that prevent and restrict freedom, but also how these are different for different women. It asserts that the rights of one group of women cannot come at the expense of another, and that equality is not truly achieved until it is achieved for everyone.

This notion of feminism stands in contrast to the fundamental principle of foreign policy as we know it: self-interest. Adopting a feminist agenda would mean overhauling the dominant components of foreign policy: national interest, prosperity, security and so on, which have been defined by those traditionally in power. A feminist foreign policy should offer a new understanding of these concepts from the perspective of the most marginalised. There is precedent for doing so.

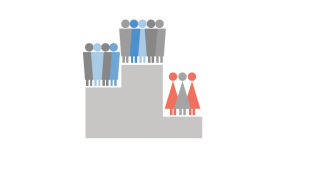

Women’s rights activists successfully lobbied for UN member states to re-examine definitions of conflict, peace, security and justice. Today, it is widely acknowledged that conflict is gendered, and differently experienced by women and girls. UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security recognises that peace, security and justice cannot be achieved without the full and equal rights and participation of women. Moreover, the UN’s sustainable development agenda, which includes a pledge to “leave no one behind”, makes clear that extreme poverty will only be successfully eradicated when the most powerless in society are benefiting from development.

For feminist activists, context is key. No action that harms women and girls occurs in isolation. It is part of an environment of discrimination, where the denial of rights for women and girls is widespread and systematic. In the UK, this means situating foreign policy within the broader context of the UK’s historical relations with the world. It means realising that others may see us differently to how we see ourselves. It means being accountable for our actions, including our colonial past and the impact it continues to have.

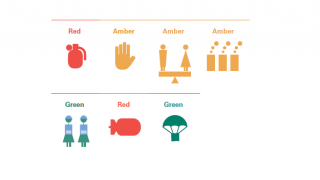

It also means practising what we preach at home. A feminist government should be willing to examine its own systems, cultures, institutions, language and behaviours to understand the ways in which they keep certain groups in power to the detriment of others. All of this is premised on a willingness to accept that inequality exists in all spheres and in all contexts.

The process of developing a feminist foreign policy must also be inclusive, consultative, diverse and representative. A government should start by opening the foreign policy space to a range of stakeholders: a grassroots women’s rights organisation needs to be taken as seriously as the most established think tank. It should appoint feminists to positions of leadership, from policymaking roles in capital cities to heads of missions overseas. This process should include the promotion of women, but a feminist foreign policy must be everyone’s responsibility. And it should commit long-term finances. Under-resourced foreign policy, with projects that rely on unpaid labour, cannot be feminist or effective.

Underpinning all of this is the need to question the very purpose of foreign policy. There is a difference between a foreign policy that has strands of work focused on women and girls, and one that seeks to undo structures of power that deny women and girls their rights. By adopting feminist language in their international policies, the Swedish and Canadian governments are setting important precedents. But they risk diluting a fuller understanding of feminism if they promote a largely unchanged global system.

If this vision for a feminist foreign policy seems nebulous, one only has to look at the work of feminist peace activists to see it in practice. Earlier this year, Afro-Colombian human rights defender Charo Mina-Rojas addressed the Security Council. She has fought tirelessly for the cultural, territorial and political rights of Afro-descendant women and peoples, including their participation in the country’s peace process. A genuine feminist foreign policy would make her work the norm, rather than the exception.

Photo: Over 70% of all trafficking victims are women and girls. Credit: Martine Perret. Copyright UN Photo.