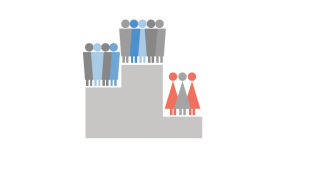

A little over a year ago I found myself fresh out of graduate school with an MA in Gender Studies under my belt. My time at SOAS, University of London had planted the seed for the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy; I had just spent the year intensely researching the intersection between feminism and international relations (IR), and had grown increasingly frustrated by the sexist and elite structure of foreign policy. Where feminist theory was indeed applied, it was used to produce recycled narratives that only focused on including more women, or constrained women into victim and/or peacemaker roles. There seemed to be a gaping chasm between what feminism was actually calling for, and the political theories, like realism, that were taken seriously and put into practice. Not only could the collision of feminism and realism yield new and different knowledge, but it could also create a path for feminist analysis to be taken seriously in politics.

And so, my attention became more and more drawn to Sweden's recently announced feminist foreign policy. I saw it as the perfect opportunity to make feminism the new status quo, and quickly became consumed by this revolutionary idea. Because feminism - true feminism - is much more than simply including women, and then placing the burden of peacebuilding on their shoulders. It’s not even wholly about gender equality, although that remains its foundation. Feminism is about power: deconstructing it, understanding it, challenging it. Identity, and especially gender identity, plays an extraordinary role in developing relational dynamics and maintaining inequality, and feeds into how we view and understand one another at both an individual and state level. Feminism brings abstract and institutional power relations full circle by grounding it in the human experience, and draws attention to the consequences people suffer at the hands of unequal power dynamics.

In recent decades there had been considerable interest in connecting global processes to local consequences and the gendered repercussions that this analysis reveals. But traditional political theories still retain an overall commitment to a system of state sovereignty. Ultimately, gender is not taken seriously beyond those who already understand its importance. States remain the dominant way that politics is organised, and that political identity is established. So, theorising and thinking about IR will always reflect the state as central. Ultimately, human experience and livelihood tends therefore to be left out of political processes. The reality, of course, is that a state is a body of people who are organised in a series of intersectional interactions, which include race, gender, and class, among many others. Though a gendered hierarchy of thinking in politics and in society is one of the most obvious, there are many other forms of identity which are long due consideration.

And so, fuelled by a deeply rooted desire to bridge such a chasm - and ever the one to bite off more than I can chew - the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy was born. We first began in September 2016 as a simple Twitter account. In December of last year (2016), we launched a barebones website, and since then, have ballooned into a team of almost 20, operating in multiple countries. We host networking and educational events, produce an online and in-print journal that highlights emerging and established voices, and develop campaigns to rectify human rights violations around the world. Our goal is to provide a space where people can share their ideas, all with the aim of encouraging a feminist approach to foreign policy worldwide.

As an organisation, we believe a feminist foreign policy focuses on the human impact of foreign policy and actively pushes back on special interests, which play far too large a role in the development of policy initiatives. It questions the realist assumptions and theoretical underpinnings of discussions around state power, where a privileged masculine consciousness dictates politics. Policy with its roots in realism encourages an abstraction of consequences, and skews reality through the detachment of context, language, and subjectivity, leaving the impact policy has on people forgotten. A specifically feminist re-visioning of foreign policy would include the previously ignored human experience. The stories that inform policy and political processes would be grounded in historical and cultural contexts which consider power dynamics and asymmetrical social relations. Such a feminist rethinking of politics would also recognise the ways in which emotion, identity, and desire intertwine to produce greater state narratives. And while IR can be a heavily militarised discipline, adding feminist theory into the mix provides a balance to such a hyper masculine focus, making room for a more complete and nuanced story.

In short: feminist foreign policy is foreign policy for the future. Without it, we can never fully comprehend the consequences state decisions have on individuals, nor move forward toward a more equitable, peaceful future. I am daily in awe of the astonishing community of inspiring and ambitious feminists we’ve built over the year. Everyone involved with this project volunteers their time and talent - we are truly a grassroots movement. If you’d like to learn more about what we do and support our work, wander over to our website: www.centreforfeministforeignpolicy.org. We have a rolling call for journal contributions, run an Ambassador Program that signal boosts our campaign work, and have a Membership Program to help sustain the work that we do and connect our community.

Photo: the launch of the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy's printed journal. Credit: CFFP