Why the UN’s financing for development conference needs to go beyond aid to meet the challenges of the next era of development.

Last year the UK quietly achieved the long-standing international target of spending 0.7 per cent of Gross National Income (GNI) on overseas development aid (ODA). With an election looming this seemed to fly mostly below the radar in the UK, but it has been a flagship element of the Government’s foreign policy abroad.

Just a few of the UK’s aid accomplishments recently highlighted by the Department for International Development (DFID) include:

- 3 million people in six countries supported to achieve increased food security

- 4.3 million babies delivered with the help of nurses, midwives or doctors

- 13 countries supported by DFID in freer and fairer elections

The UK has also become the world’s largest funder of multilateral aid, delivering £6.3bn through these channels in 2013 – 50 per cent more than any other country. With this comes the potential for increased influence in global development forums, as seen in the Prime Minister’s recent co-chairing of the High-Level Panel on the Post-2015 Development Agenda.

A 2013 House of Lords inquiry into the UK’s soft power similarly concluded that the aid spending projects “a vision of the UK as a helpful and generous nation that can provide expertise in effective international development.”

It has even been suggested that DFID’s global reach and reputation may play a greater role in British diplomacy than the more traditional approach of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO). This is a remarkable shift. Until 1997 DFID was a sub-section of the FCO, but now it commands its own protected annual budget of around £11bn. By comparison, FCO spending is roughly a quarter of DFID’s, with some FCO work ‘badged’ as ODA in line with DFID priorities.

The bigger picture

So how does this dramatic shift in UK aid spending compare with wider trends? According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), ODA has risen steadily in absolute terms and reached near-record levels in 2014.

However, as a proportion of GNI, spending has stagnated, and was lower in 2014 than in 2005. The OECD average in 2014 was 0.29 per cent, with contributions from France and Canada in particular declining over recent years. And despite numerous public pledges to the contrary, just six countries have actually met the 0.7 per cent target: Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom.

Equally concerning is the sharp reduction in aid going to the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) – the 48 poorest countries on the planet, 34 of which can be found in sub-Saharan Africa, and which are often wracked by long-term conflict and instability. Figures show that ODA spent on LDCs in 2014 fell by 16 per cent from 2013 levels.

The OECD suggests that donors favoured middle-income countries, such as China and India, where the majority of the world’s poor can still be found. Yet LDCs are far more reliant on ODA for the provision of essential services, with 40 per cent of government budgets being comprised of foreign aid.

Another area where aid is falling far short of requirements is the financing of global public goods. These are the resources and services which mitigate global risks for the benefit of all countries, such as disease control, conservation and agricultural productivity. But according to the Center for Global Development, in 2012 less than a tenth of ODA ($12bn) was allocated to global public goods – of which nearly $9bn went to UN peacekeeping alone.

Though not new, these concerns become increasingly urgent at a time when, under the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the pressure on the system is set to grow considerably. Since 2012, the UN’s highly-anticipated SDGs have been meticulously consulted on and negotiated over, and are due to be adopted in September.

Billed as a successor to the Millennium Development Goals, the zero draft’s 17 goals and 169 targets (see box below) go far beyond the eight – much narrower – MDGs embarked upon in 2000. Universal in their scope, the SDGs are intended to transform not only the poorest nations but the world’s approach to its most intractable social, economic and environmental problems.

Considering the alternatives

If the ‘what’ of the SDGs has been all but decided, then an upcoming UN conference must answer the ‘how’. Aid is clearly one (albeit important) vehicle for development. But in July, member states will meet in Addis Ababa for the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, where they will explore the alternatives.

Public finance

States are expected to pay a lot of attention to the resources that can be raised in-country. Tax revenue in lower-income countries typically stands at just 10–14 per cent of GDP, compared to 20–30 per cent in high-income countries. Despite the impressive results of capacity-building programmes for revenue officers – one $15,000 project in Colombia saw tax collections jump from $3.3m to $5.8m in just one year – only 0.07 per cent of ODA was spent on this in 2012.

Ahead of the Addis conference, campaigners have been calling for states to commit to mobilising domestic public finance of at least 18–20 per cent of GDP, and using this income to fund a minimum spend of $300 per capita (or 10 per cent of GDP, whichever is greater) on basic essential services.

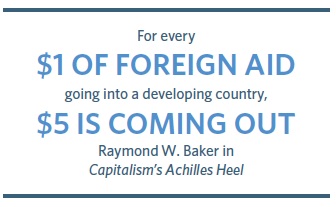

Tax is increasingly an area which also requires international cooperation. It is thought that developing countries lose $500bn in tax evasion annually. While the G7 and G20 have been proactive on this issue, much more remains to be done to end the problem of tax havens and to improve the transparency of financial reporting.

Private sector and trade

Lauded by the UK Government and others as the key that will unlock developing countries’ potential, foreign direct investment will also feature strongly in Addis, particularly in relation to high-impact infrastructure projects.

Public-private partnerships are likewise viewed as a potential solution to a number of financing dilemmas. Some have undoubtedly made important progress but a recent study of 330 multi-stakeholder partnerships, undertaken by the International Civil Society Centre, found that 38 per cent were inactive.

Developing countries will also want to focus on removing the barriers blocking their growing influence in trade. South–South trade has prospered in recent years, rising from eight per cent of all global commerce in 1990 to 25 per cent last year.

Financial inclusion

More than 2.5 billion people around the world have no access to formal financial services, stymieing their ability to save income, start small businesses and contribute to the broader economy.

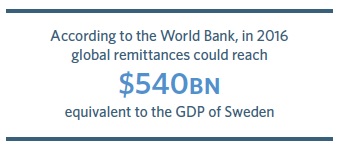

Remittances are a popular option, but governments must address the unacceptably high associated costs, which can be as much as 20 per cent for intra-African transfers.

In many cases, however, these obstacles have resulted in some innovative alternatives that could usefully beharnessed for wider benefit. Kenya’s M-Pesa has featured in the pages of New World as an excellent example of mobile money transfer that could be replicated elsewhere.

Mind the gap

What is clear is that to implement such an ambitious range of development goals, each will require its own unique range of public and private, national and international finance. However, the gap between expectations for the Addis conference, and what can realistically be delivered, is significant.

Global finance governance operates in a highly fragmented policy environment. Although the UN is the only international organisation with the universal membership to address such a global issue, its clout is limited. Almost from day one the UN deferred this responsibility to two independent, specialised agencies – the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). But its Bretton Woods offspring have long since flown the nest.

The World Bank, for example, has embarked upon its own poverty eradication agenda while its President, Jim Yong Kim, has been largely silent on the SDGs. The OECD, meanwhile, has launched the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, a programme pursuing ultimately the same ends as the Addis conference.

Add to this the G7 and G20’s leadership on tax reform, the IMF’s preoccupation with debt crises and a new BRICS-governed development bank, and you soon begin to appreciate the scale of the challenge in converging the interests of these institutions with 193 member states.

A 2009 Commission headed by economist Joseph Stiglitz made suggestions for how to improve the coordination of this cumbersome system. These recommendations remain highly relevant six years later but continue to gather dust.

Navigating these issues is the responsibility of the Addis conference’s co-facilitators, the Permanent Representatives of Guyana and Norway (as well as hosts Ethiopia), yet they may find the solutions are above their pay grade. It is vital they succeed, not only for the effective delivery of the SDGs but to ensure the agenda even gets off the ground.

As UNA-UK policy advisor, Alex Evans, recently put it, a poor outcome at Addis could “poison the atmosphere for the SDG summit in September and potentially the climate summit in December too, creating the risk of a cascading multilateral failure.”

A failure of this kind is a risk, but not a foregone conclusion. Civil society must get behind the conference as a critical moment in building political will for the SDGs. It also needs to be a firm date in the diary for the world’s finance ministers as they are the only ones with the authority to seal the deals needed. It is worth asking, is your finance minister attending?

Photo: in partnership with the World Food Programme, MasterCard is providing the technical expertise that enables Syrian refugees to use prepaid cards to buy their own food. ©Flickr/MasterCard News