Among the proposed 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set to be agreed by the UN this September is the widely advocated goal on gender equality. Under its targets UN member states will be required to provide women with “equal opportunities for leadership”; to recognise and value unpaid domestic work; and to prevent violence against women. But as the latest report by UN Women points out, a goal on gender equality cannot achieve substantive gains for women merely through setting international norms, or even domestic legislation. It must be directly incorporated into economic policy.

The report, ‘Progress of the World’s Women 2015-2016’, dismantles the general presumption that economic and social policy must operate at two ends of the spectrum. Neoliberal values dictate that economic development is measured by high Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and low inflation; the pursuit of capital should be unburdened from any thought of citizen welfare. Social policy, therefore, is developed in response to certain consequences of economic decisions – it rescues the vulnerable from being trampled on by those equipped to thrive in a free market. Perpetuating structural bias and discriminatory social norms, this approach is a major obstacle to women achieving a quality of life that equals that of men.

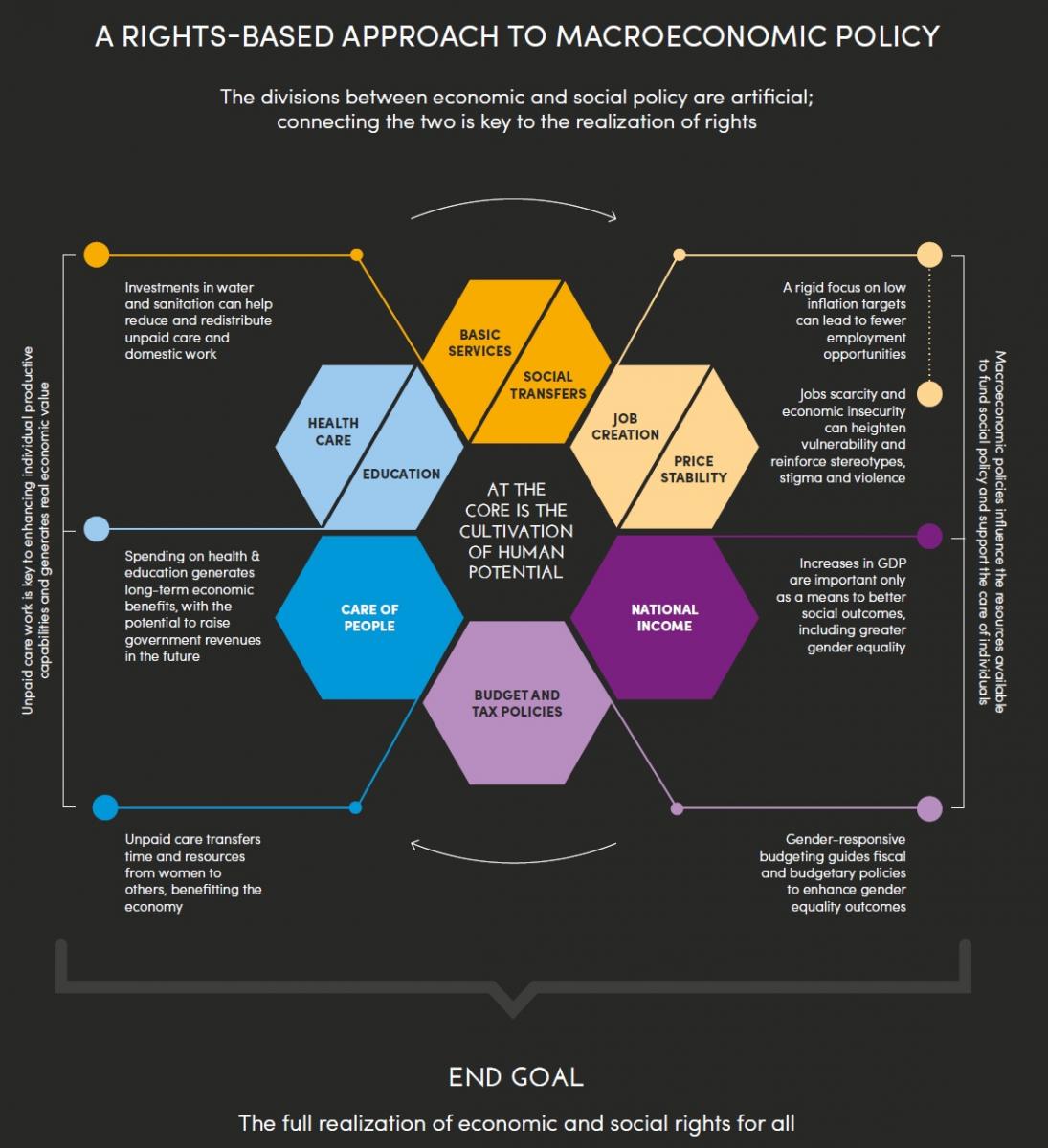

Rights-based economics

Instead, the report goes, we need a rights-based approach to economic policy. By expanding fiscal policy to include the creation of decent jobs for women, greater recognition of domestic workers (83 per cent of which women), consultation with women’s movements and greater investment in social services, we could provide realisable opportunities for women.

This is an important time for this shift to take place. With many countries emerging from economic crisis, women are increasingly being forced to accept low-paid, insecure jobs, deepening gender disparities even further. The current ‘gender-neutral’ approach to policymaking is inadequate as it fails to redress women’s socio-economic disadvantage, and does not remedy existing stereotypes and stigma that are so deeply ingrained in many societies.

Click on the infographic below for larger version:

It is a new, revolutionary proposal that jars against our traditional understanding of how society functions. Why, one might ask, does economic growth have anything to do with the separate field of human rights protection?

There is already a plethora of international and domestic law that lays the groundwork for women’s empowerment. By 2014, 59 countries had passed laws stipulating equal pay for men and women, while the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is one of the most widely ratified treaties, with 186 signatories. Surely the conflation of social policy with economics could result in the failure to achieve significant progress in either?

But as Laura Turquet, UN Women researcher and report manager, noted, this concern can be dispelled by asking the simple question: “what is the economy for?” Just as Oxfam’s Executive Director Winnie Byanyima observed that “you can’t eat GDP”, UN Women recognises that an economic boom does not necessarily mean better lives for all. Over 70 countries still restrict the types of work available to women, while data from France, Sweden, Germany and Turkey show that women earn between 31 and 75 per cent less than men. As soon as policymakers recognise that the ultimate purpose of GDP growth is to improve the lives of individuals, rights-based economics starts to make sense. It is an approach that treats citizens as the ends, not just the means, of a thriving economy.

Re-working human rights

But by making the case for incorporating human rights into economic policy, UN Women wades into a deep-rooted disagreement about what counts as a human right, and what states have to do to achieve them. Incorporating social welfare into monetary policy implies that we, as humans, have an inalienable right to these things; that our governments have a duty to supply them. As the history of the UN human rights system shows, this is a disputed premise.

The early division of the UN’s core human rights instruments into the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) signalled a global disagreement on what constitutes a basic right. As noted by Amnesty International US, the Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations believed that economic, social, and cultural rights were not rights per se, but desirable social goals.

To this day, Western countries generally maintain that human rights require the state to leave citizens to their own devices. This is why the ICCPR contains mostly ‘negative’ rights, such as freedom from torture and freedom of expression, while the ICESCR contains ‘positive’ rights that require state provision of fair wages, healthcare and maternity leave. The abstract principle of “progressive realisation” of rights was therefore incorporated into the ICESCR, obligating a state to merely comply with the articles “to the maximum of its available resources”.

The UN Women report, therefore, defies the developed world’s hands-off approach to human rights. It recognises that it is no good providing women with opportunities for decent jobs if there are social obstacles that prevent them from taking them up. As Swedish Foreign Minister Margot Wallström recognised in her defence of a “feminist foreign policy”, we will never achieve gender equality “without adjusting existing policies, down to their nuts and bolts, to correct the particular (and often invisible) discrimination, exclusion and violence still inflicted on the female half of us.” This means that it is not enough to progressively realise economic rights; provisions must be made in a state’s national budget and macroeconomic policy to achieve these rights.

Achieving substantive equality

Improving the prospects of all therefore requires states to “free up women’s time”, as Executive Director of UN Women Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka claims. This translates to greater state investment in childcare and ensuring women can return to well-paid, stable work after having children. It requires meaningful participation of women’s movements in policymaking and encouraging girls to study traditionally male-dominated subjects. Maintaining a rigid focus on low inflation might see a rise in GDP, but it can also lead to fewer jobs and the devaluation of lower-paid domestic workers.

The latest UN Women report is therefore not only innovative in its proposal to meld human rights with economic policy; it is ground-breaking in the sense that it sets a high benchmark of what counts as human right. The report claims that it is not enough to agree to a standalone goal on gender equality, or even to include it in domestic policy. Women have the right to the same socio-economic opportunities as men, and governments are obligated take positive, resourced measures to achieve this.

Isabelle Younane is Communications and Campaigns Assistant at UNA-UK. She holds an MA in Human Rights from University College London.

Follow @IsabelleYounane on Twitter

Infographic: UN Women

Photo: Girls from Kuma Garadayat celebrate the inauguration of Quick Impact Projects, implemented by the African Union-UN Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID). These projects focus on the areas of education, sanitation, health, community development, and the empowerment of women. Copyright UN Photo/Albert González Farran