The words I heard the most during my week in Amman, the capital city of Jordan, were ones of welcome. My friendly hosts – epitomised by the innumerable taxi drivers who ferried me through the steep, congested streets – were keen to make sure I was enjoying my visit, seeing the historical sites and eating the local dishes.

Unlike the tourists however, who generally opt to leave Amman for the Dead Sea or Petra, I spent most of my time inside the offices and centres of international organisations, embassies and charities. I was there to get a better sense of how a country like Jordan copes with the spill-over effects of conflict in the region. How do you deal with the needs of those fleeing conflict, while ensuring that the host state does not fall apart as well?

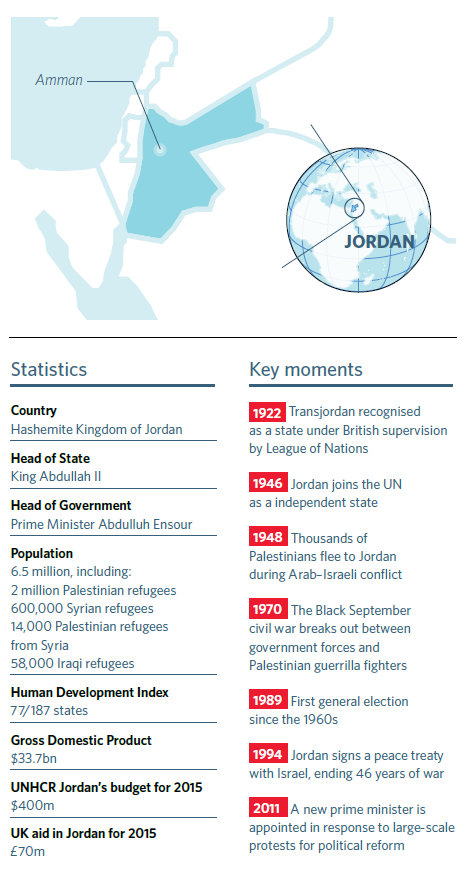

Bordered by Syria to the north and Iraq to the east, Jordan is under a lot of pressure. It shoulders a heavy burden for the international community, receiving thousands of refugees daily and acting as a buffer against the spread of conflict across its borders. Unlike other states in the region, Jordan is not yet visibly buckling under the strain. However, the situation is a test of the country’s resilience.

Humanitarian agencies, donors and charities have their work cut out, not just to help look after the populations fleeing violence, but also to bolster the Government’s capacity to manage the additional challenges and pressures this brings. It is a complex tapestry of prevention and protection; hosts and refugees, humanitarian aid and development assistance, all interlinked, all requiring short- and long-term responses, all needing more financial support.

It is almost four years into the conflict in Syria and a year since Islamic State (IS) started to gain ground both in Syria and Iraq. There is no doubt that Jordan has been incredibly generous thus far. However, there are limits to what even the most hospitable hosts can reasonably deal with, and in truth, Jordan is struggling. As the conflict in Syria has deepened, and Iraq has all but imploded, Jordanians have found it difficult to come to terms with the fact that the refugees will keep on coming, and will not be going home any time soon.

The situation is all too familiar for this weary nation, which has a lengthy history of hosting refugees from numerous past conflicts in the region. As a small population, Jordanians have long feared becoming strangers in their own home. Their limited resources and infrastructure and public services are groaning under the increased demand. Now the second water-poorest country in the world, Jordan relies on its neighbours, particularly Israel, for water and energy supplies. The rapid growth in population has added pressure that has simply not been planned for, exacerbating these challenges and making economic reform ever more urgent.

The UN’s bread and butter

I began my time in Amman – like the refugees – at the UN Refugee Agency’s (UNHCR) registration centre. Housed in a converted school, the complex was opened in September 2013 to enable the Agency to deal with the huge number of applications. I entered the compound through the only entrance the taxi driver knew – the gate for those wishing to register as refugees.

Expecting it to be crowded with people, I was a little disappointed to find that by the time I arrived, everyone had already been processed. The rows of empty benches were testament to the efficiency of the UNHCR staff, who were enjoying a well-earned cup of tea in the sunshine after having dealt with around 3,000 applications that day.

“Last year, we had a backlog of over nine months of applications as we didn’t have the space or capacity to deal with the demand,” Aoife McDonnell, UNHCR’s External Relations Officer, told me while we walked through the maze of temporary prefab buildings surrounding the complex. “Once we moved here, we worked 24/7 and managed to get through it in two months. Now we can register people on the day they arrive and make sure they have all the information they need in one visit. We aim for it to be a one-stop-shop for refugees.”

For Aoife, the centre’s work is the “bread and butter” of what UNHCR does. The staff is trained to assess refugees’ safety and detect any potential protection issues, from domestic violence to child marriage to smuggling. They give out free Jordanian SIM cards so that the Agency can keep in touch and run a call centre to deal with follow-up issues. I was there just days after the World Food Programme (WFP) announced that it lacked the funding to provide food vouchers to Syrian refugees. The computer screen at the back of the call centre displayed a mountainous spike next to WFP’s logo.

Spare a thought for the locals

While the refugee camps are well publicised – such as Zaatari camp, said to be the country’s fourth largest city – 85 per cent of registered refugees actually live in urban areas, like Mafraq or Amman. “The camps can be seen as a safety net for Syrians,” explains Aoife, “but urban settlement is our most desired response. It’s cheaper as there is better infrastructure and existing services; we can provide cash assistance that gives them freedom to choose how to live; and it doesn’t build a dependency, people find it easier to reintegrate into normal life once they return to their country of origin.”

However, settling large numbers of people in Jordan’s towns and cities has caused difficulties. Jordan has already faced deep economic challenges, and in the past three years local authorities have seen the kind of growth they had expected over the next 20. Increased need for housing has seen rents in some areas almost triple. Refugees represent a large supply of informal, cheap labour, and increasingly child labour, which potentially puts Jordanians out of work. Local schools are struggling to cope with the inundation of Syrian children, who make up half of the refugee population. People, particularly the poorest, are seeing their living standards fall as a result of the strain.

Surprisingly for a state that accepts so many, Jordan is not a signatory of the UN Convention on Refugees. The work of organisations to protect and assist them is based on a 1998 Memorandum of Understanding between the Government and UNHCR. All humanitarian programmes need to be approved by the Government and between 30 and 50 per cent of aid and investments must be targeted towards strengthening the host communities.

Jordan’s national resilience plan encourages donors to deliver assistance through its own channels, rather than through the parallel services of the aid agencies, so as to increase its own capacities and infrastructure. Financially, Jordan estimates that it will need to spend $1.6bn, around three per cent of GDP, to maintain the current level of basic services over the next year (see stat box, right).

Under pressure

Nevertheless, despite the best efforts of all those involved, the pressure is becoming too much. The perception of the refugees among Jordanians has become increasingly resentful, potentially toxic. While attending a UN workshop on atrocity prevention, relations between refugees and host communities was flagged as being the most concerning trend for Jordan’s future stability.

Those working in the country are becoming increasingly uncomfortable about the direction in which the Jordanian Government is going and insisted that we talk about the situation off the record. They fear that government policies are failing to address community tensions, even tacitly supporting negative viewpoints through some of its own policies.

It is difficult for a registered refugee to gain access to a permit to work legally, and their access to education and health services is gradually constricting. The Ministry of Labour guards a number of professions for Jordanians only, keeping Syrians out of industries such as medicine, engineering, administration and construction, despite the fact that they could make a beneficial contribution to the economy in terms of boosting skills and paying taxes. Aid agencies and donors are not allowed to undertake vocational training programmes for Syrians, leaving many without the opportunity to develop skills that could help both Jordan and Syria in the future. In 2013, a Jordanian official was quoted as saying that the Government “does not want to enhance [Syrians’] engagement with the rest of society”.

Additionally, the current trend in the region, not just Jordan, is towards the restriction of the free flow of refugees. Late in 2014, Jordan unofficially closed its borders. Reports based on the testimonies of refugees who made it through claimed that some 5,000 people were stuck on the Syrian side of the border, with little access to assistance or protection. Even before this happened, Syrians had started to look for refuge elsewhere: between January and September 2014, the number of Syrians crossing into Jordan shrank from 60,000 per month to 10,000.

Special treatment?

The situation is arguably worse if you are a Palestinian refugee fleeing Syria. The Jordanians’ concerns about accommodating refugees has been deeply affected by Black September, the 1970–71 civil war between the Government and Palestinians aligned with the Palestinian Liberation Organisation. More than half of Jordan's population already come from a Palestinian background, and the country is not keen to accept many more.

US-based NGO Human Rights Watch has documented the deep discrimination against Palestinian refugees from Syria since the Jordanian Government closed its borders to them in 2013. There are 14,000 registered in Jordan, although experts suspect there are many more who are afraid to identify themselves. Over 100 have been forcibly (and illegally) returned to Syria and authorities have reportedly been confiscating documents, sometimes as punishment for crimes like working without a permit. It is reported that at least 115 Palestinians have returned to Syria voluntarily, for lack of a better option.

A meeting with the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), a specialised organisation working to protect and assist Palestinians across the Middle East, painted a depressing picture of the challenges facing this population. With only 40 per cent of the necessary funding, UNWRA manages to provide cash assistance to every refugee registered with them, as well as education, health and social services. In many ways, UNRWA takes the place of the state, but without the powers to tax and with donors trying to deal with the pressures of crises worldwide and austerity at home, it needs over $400 million in donations to maintain current levels of activity.

There has been a sad realisation among many Syrian Palestinian refugees that there is no future for them in Syria – and perhaps not even in the region. Burdened by a double refugee status, they quite literally have nowhere else to go. Those who can, send their working-age sons to Europe on overcrowded people-trafficking boats, others smuggle themselves into Turkey, knowing that they cannot legally come back. For them, this crisis is bigger than Syria. A solution to their problems is a crucial part of the future stability of the Middle East. UNRWA’s Regional Chief of Staff, Lisa Gilliam, had a clear message for me when I met her: “we must not forget them”.

Generosity begins at home

As a result of the burden of hospitality, there is less and less room for refugees in the region. Jordan is one of the more stable examples in the Middle East but with the crisis in Syria continuing, and Iraq getting worse, the country can expect only increased pressures on its already straining infrastructure and tense social relations. I asked everyone I met with what their main message was to those in the UK and there was a resoundingly clear answer: we need more money. Higher rates of resettlement of refugees in Europe, including in the UK, could alleviate pressure on Jordan and other host countries. More substantial economic reform would help in the medium and long term. An improved public narrative on refugees might defuse tensions. But short of actual peace in the region, money for effective programmes, aimed at easing the pressure on Jordan, is the only answer available.

If there is any hope for Jordan amid this unparalleled humanitarian crisis, it can be found in the energy and optimism of the UN staff I met during my time in Amman. Under no illusions about the difficult context in which they work, they keep pushing to protect vulnerable populations – both refugees and hosts – in a deteriorating political environment. In order to prevent further damage, they need our support and our hospitality.

Alexandra Buskie is UNA-UK’s Peace & Security Programmes Officer. She would like to express her gratitude to the UN Office for the Prevention of Genocide, the International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect, the Permanent Peace Movement and all of the agencies and organisations she met with and reached out to for their help in facilitating this trip

Photo: a Syrian refugee family gather on the floor of their dilapidated apartment in downtown Amman, Jordan. © UNHCR/B.Szandelszky