For nearly 70 years, UN peacekeeping has intervened in some of the world’s most violent conflicts, with varying degrees of success. As the latest review of the UN’s peace operations gets underway, New World asks, is it still up to the job?

Despite being one of the most iconic parts of the UN system, peacekeeping was not expressly included in the Organization’s founding document. Reading between the lines of chapters six and seven of the UN Charter, however, the Security Council has been authorising peacekeeping operations as part of its responsibility to maintain international peace and security since 1948.

In those early days, peacekeeping typically involved the monitoring of a ceasefire agreement between two states. In its first 40 years there were just 15 operations established. Over time, three principles emerged which have underpinned operations ever since:

- consent of the parties to a conflict;

- impartiality;

- non-use of force except in self-defence or defence of the mandate.

The end of the Cold War, however, ushered in an increasingly demanding era for UN peacekeeping. Between 1989 and 1994, the Security Council approved a total of 20 new missions, increasing troop numbers from 11,000 to 75,000.

In addition, the UN also began operating in far more complex conflicts. Peacekeepers were deployed to hostile situations where there was no peace to keep, with civilians bearing the brunt of the violence and requiring major humanitarian assistance. Operations were fast evolving from providing a military presence to large, multidimensional missions involving various UN and external actors.

Tragedies in Rwanda, Somalia and the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s have since become synonymous with the UN’s struggle to adapt to this new environment, and marked a low point for the entire Organization.

Time for change

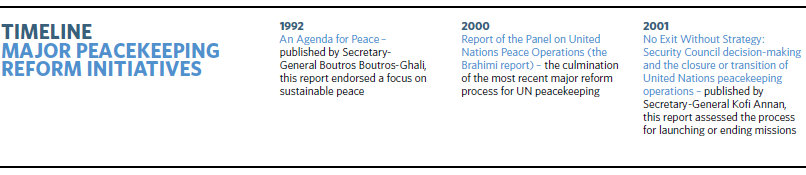

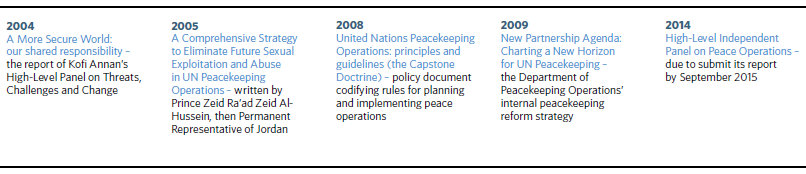

Reflections on internal reform had already begun with then Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s 1992 report, An Agenda for Peace, which called for a greater emphasis on long-term peacebuilding. But it was in 2000, at the behest of his successor, Kofi Annan, that the UN undertook its most influential peacekeeping reform initiative.

A panel of 10 experts, chaired by the former Foreign Minister of Algeria, Lakhdar Brahimi, assessed past failures and addressed the major challenges facing peace operations. Their subsequent report, known throughout the UN simply as 'the Brahimi report', provided a number of key recommendations:

- Peacekeeping required bigger missions that were integrated with other parts of the UN system, such as police teams and civilian rule-of-law units.

- The Security Council needed to issue clearer and more achievable mandates, with resources and strategy closely matched to need.

- Appropriate mandates required an increased Secretariat team, capable of accurate analysis of the facts on the ground.

- Missions needed to be more robust, capable of operating effectively in hostile environments, particularly where civilians were at risk.

- Operations required improved planning and logistics, as well as a greater capacity for the rapid deployment of troops in the first 30–90 days of a conflict.

Where are we now?

While the UN has gone some way to implementing the recommendations of the Brahimi report, a number of its proposals remain just that, and many of the challenges it raised are still relevant today.

Two thirds of current peacekeeping operations are in live conflict zones where the UN itself is often seen as a legitimate target (122 peacekeepers lost their lives in 2014, one of the deadliest years in peacekeeping history).

Long-running differences between the Security Council’s expectations of a mission and troop-contributing countries’ capacity and willingness to fulfil its mandate remain a significant obstacle to progress.

And even the three underlining principles of UN peacekeeping are invariably questioned. As US Ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power, put it in a speech last November: “We cannot ask extremist groups for their ‘consent’; remain ‘impartial’ between legitimate governments and brutal militias; or restrict peacekeepers to using force in self-defence while mass atrocities are taking place.”

Future challenges

Established in October last year, the High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations is tasked with providing an up-to-date assessment of the state of peacekeeping, 15 years on from the Brahimi report. Reflecting the growing trend of integrating UN peace operations, the Panel will, for the first time, also examine special political missions.

As part of its peacekeeping programme (see Natalie Samarasinghe's article), UNA-UK recently input into a briefing book, compiled by New York University’s Center for International Cooperation and the International Peace Institute, which asks 'What needs to change in UN peace operations?' UNA-UK called for greater commitment to the preventive approaches that have emerged at the UN in the last decade, such as the Responsibility to Protect and the Secretary-General’s Human Rights up Front initiative.

Other critical areas identified in the briefing include the need for a coherent policy on what the protection of civilians means in practice, how to establish a clearer framework for the growing number of joint missions with regional organisations, and ensuring that the Secretariat is structured so as to remove unnecessary overlaps between peacekeeping and political missions.

It is clear that there is an appetite for a strategic shift in the UN’s approach to its peace operations. But as with any UN reform, neither revolutionary new concepts nor institutional fixes will have any impact without the political will and backing of member states. As we continue to rely on UN peacekeeping to undertake the toughest of assignments, it is imperative that it is properly equipped for the task.

Photo: soldiers from the Indian Battalion of the UN Mission in South Sudan patrol the perimeter of the compound in Malakal © UN Photo/JC McIlwaine