Last month saw the worst riots and violence in Malawi since the early 1990s, when protestors took to the streets to call for multi-party democracy and an end to the 30-year reign of then-President Hastings Kamuzu Banda.

In recent months, tensions have resurfaced in the country, which is generally considered to be one of Africa's most stable states. Chronic shortages of fuel, electricity and foreign exchange, poor governance, worsening human rights abuses and a crackdown on academic and political freedoms culminated in demonstrations that were held on 20 July 2011.

President Bingu wa Mutharika's Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government initially tried to ban the protests but having failed, it resorted to other tactics. The day before the protests, DPP vehicles laden with thugs brandishing knives were dispatched to the streets of Blantyre, Malawi's financial and commercial centre, in an attempt to frighten people into staying away. Such intimidation is reminiscent of Banda, who unleashed his ruthless paramilitary youth organisation, the Young Pioneers, on the population.

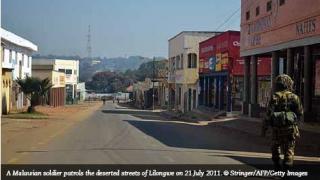

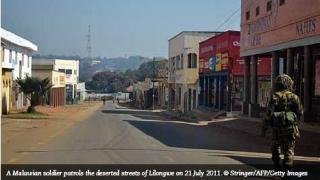

On the day itself, security forces attempted to disperse protestors almost immediately despite receiving prior notice of the demonstrations and the routes to be taken in major cities. This quickly led to violence. The crackdown, first by the police and later the army, was brutal, particularly in the capital, Lilongwe, and in Blantyre, Mzuzu and Zomba. Two days of rioting left 19 people dead and scores more injured. Non-state media were shut down and city centres were left deserted.

After the second day of violence, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon issued a statement voicing concern. His words were echoed by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Condemning the government's "excessive use of force", OHCHR stated that it had received reports of mass arrests, harassment of journalists and death threats against protest organisers. It called for "prompt, impartial and transparent investigations into these allegations of grave human rights violations".

Not able to leave my compound, I watched events on the Chileka Road in Blantyre from afar while hundreds of people fled the tear gas and live bullets fired by the police. Gunshots rang out long into the night from surrounding townships as security forces tried in vain to prevent looting and further violence. Tyres and barricades were set alight at strategic junctions all over town and were still smouldering the following morning.

Expecting calm to return the next day, I went into central Blantyre and was on Victoria Avenue when tear gas and shots were fired and truckloads of soldiers deployed mid-morning. I had to run a few blocks and walk home. The second day of riots was much more severe in Lilongwe and Mzuzu.

The president spoke to the nation on both days but failed to address the protestors' grievances in his rambling speeches. He vowed to "smoke out" those who had organised the protests or otherwise opposed him, threatening to arrest the vice president and to "deal with" opposition leader John Tembo. His refusal to acknowledge concerns, let alone provide solutions, has led to the planning of further protests.

Mutharika, who was re-elected in 2009 with an overwhelming majority, has seen a dramatic change of fortune in his second term. He has compounded frustrations arising from the worsening economic situation by pushing through a number of controversial laws and initiatives, including wasting money on changing the country's flag, purchasing a new presidential jet (at a cost of $22m) and a fleet of Mercedes (costing $4.8m), and travelling with an excessively large entourage on foreign and domestic trips. In one of the poorest countries in the world, where over half of the population lives below the poverty line, such expenditure is hard to justify.

A further indication that Malawi is facing a return to autocratic rule was the expulsion in April 2011 of the British ambassador. The UK subsequently withdrew financial support to the Mutharika regime and a number of other donors, notably the US, have suspended grants following July's crackdown.

President Mutharika's term is not due to end until 2014. Before the protests, most people seemed content to sit it out, but July's events suggest that this is no longer the case. If the economic situation fails to improve and further crackdowns occur, there is a real possibility that Malawi, the once-stable 'warm heart of Africa', could see protests on the scale of those in Egypt and Tunisia.

Andy Stephens is currently working for an NGO in Blantyre, Malawi, and writes here in a personal capacity