Zoya Phan is a 30-year-old ethnic Karen refugee from Burma. As a teenager she was forced to flee her village after an attack by the military junta and now works as Campaign Manager for Burma Campaign UK, an award-winning organisation campaigning for human rights, democracy and development in Burma.

Below is a longer version of the interview featured in the print version of the Autumn 2011 issue of New World magazine.

Burma is considered to be one of the world’s most secretive - and repressive - countries. How would you describe it to those who are unfamiliar with its history?

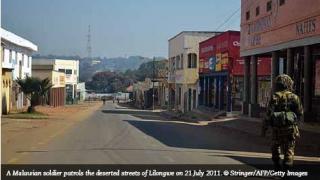

Burma is ruled by one of the world’s most brutal dictatorships, which kills, tortures and imprisons civilians who work for human rights and democracy. The dictatorship has also been engaging in war against ethnic groups for several decades.

Burma is incredibly diverse, with eight major ethnic groups and over 130 ethnic minorities, and ethnic people have been subjected to constant repression. The Burmese Army deliberately targets civilians: raping, looting, killing, torturing and burning villages. As an ethnic Karen, I have twice been forced to flee my homeland because of attacks by the Burmese Army.

What are the most pressing issues that need to be addressed on Burma?

The dictatorship commits a host of systematic human right violations - including forced labour, extra-judicial killings, forced relocations, extortion and land confiscation. The denial of aid by the regime is widespread. The humanitarian crisis and the levels of poverty and disease are as high as in the worst conflict zones in Africa, but attract little attention from the international community.

Again, it is ethnic minorities that often bear the brunt. In Eastern Burma, more than 3,600 villages have been destroyed in the past 16 years and hundreds of thousands of people from minority groups continue to be used as slave labour. The regime’s troops use rape as a weapon of war against ethnic women, and their soldiers rape girls as young as five years old.

The UN has called for ethnic leaders to be included in dialogues between the regime and democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi, but has made no serious attempts to facilitate this. The situation is unacceptable. Without participation from ethnic political groups, there can never be peace in the country.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s struggle has often been the catalyst for media coverage of Burma and for keeping the country on the human rights agenda. But it has also led people to reduce a complex situation to the story of one individual. Has her release, after some 15 years in detention, made a difference to ordinary people?

Aung San Suu Kyi’s release gives hope to the people. But it doesn’t signify democratic change as it was not part of a political process. The regime released her simply because it wanted to get positive publicity after the blatant rigging of the 7 November 2010 elections.

Some 2,100 political prisoners - including MPs, student leaders, monks, journalists, ethnic leaders, and artists - are still languishing in jail, and attacks against civilians in ethnic areas continue, forcing thousands people from their homes. Human rights abuses are increasing and the humanitarian crisis is as dire as ever.

Your personal story is worthy of as many column inches as Aung San Suu Kyi's - tell us bit more about yourself.

When I was 14, the Burmese Army attacked my village in Karen State, Eastern Burma, and I was forced to flee. I lived in a refugee camp in Thailand that was more like a prison camp. It wasn’t safe; we weren’t allowed to go out and were completely dependent on aid from NGOs. People in the camp live in hope that the situation in Burma will get better so that they can return home. But it hasn’t.

I was very lucky. I got a scholarship to study in Bangkok and then in the UK. In 2005, I started working with Burma Campaign UK to promote human rights, democracy, and development in my homeland.

My dream is that everyone in Burma will be able to live in peace, security and freedom regardless of our ethnicity, race, religion and gender.

Tell us about your work. What are you most proud of achieving?

Burma Campaign UK works together with many other organisations to raise awareness of the situation and push for stronger international action against the dictatorship. In my role, I’ve had the opportunity to speak out about the suffering: I met twice with former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown and his successor, David Cameron; and with celebrities and governments across Europe to ask them to take stronger action against the dictatorship. We are grateful that Burma continues to be prominent in the international political arena, especially on the UN Security Council’s agenda.

We are especially thankful to the UK, which remains one of the most supportive governments as well as a generous donor. In 2007, for instance, the UK doubled its humanitarian aid to Burma and helped to save the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

Your mother was a guerilla soldier, your father an activist. What would you have been had you remained in Burma?

When I was little, I wanted to become a teacher - education is vital if we are to learn to read and write, and preserve our language for the next generation. The dictatorship holds on to power by denying education to its people, especially ethnic minorities, so young people don’t have the opportunity to fulfil their potential.

Both my parents were very active in resistance work for freedom and peace. Their determination inspired me to take up their struggle. Having grown up in a military dictatorship and witnessing its horrible abuses against the people, I wanted to work to promote human rights and democracy in Burma.

Given your experiences and what you have witnessed, do you want to go back to Burma?

I want to go home, and I know many others forced to flee who want to go home too. But as long as the regime is in power, the international community fails to take effective action, and there is no peace in Burma, I won’t be able to return.

Are there lessons for Burma from the ‘Arab awakening’?

As Aung San Suu Kyi has said, the difference between Burma and, say, Tunisia and Egypt, is that in Burma the soldiers open fire on protestors. If protests are to be used as a tactic, we need to develop a strategy to persuade ordinary soldiers not to shoot. It is also frustrating to see that when people took up arms to defend themselves against abuses in Libya, NATO helps them. But when ethnic people take up arms in Burma to defend their villages from similar attacks, they get criticised and even blamed for the violence and get no help.

Burma was under British rule until 1948. As the former colonial power, do you think the UK has a special role to play in Burma today?

I think all countries have a responsibility to promote human rights and democracy everywhere in the world. But as an ethnic Karen, we and other ethnic groups, do feel let down by the British. We fought with them against the Japanese in World War Two and were promised autonomy and our own states, but the British government abandoned us at the time of independence, and more than a million ethnic people have now died because of the central government’s use of military force against ethnic minorities. I think Britain has a special responsibility because of this betrayal.

What do you think of the UN's current approach to Burma and what action should it be taking?

In my opinion, the UN has been ineffective in dealing with Burma. Although it has accused the dictatorship of breaking the Geneva Conventions by deliberately targeting civilians, there hasn’t been a UN investigation into these crimes. The UN should set up a commission of inquiry into war crimes and crimes against humanity in Burma.

It is important for the international community to understand that the regime in Burma is not interested in democratic reform, but only power and control. It is high time that the UN and others pressure the regime, politically and legally, to enter into negotiations with Aung San Suu Kyi and leaders of ethnic political groups, on the release of all political prisoners and a nationwide-ceasefire.

If you could send a tweet to the UN Secretary-General, what would it say?

Learn from 20 years of UN mistakes in Burma: ‘softly softly’ doesn’t work.

Zoya Phan is Campaigns Manager at Burma Campaign UK and a member of UNA-UK's Young Professionals Network - a network of people in their 20s and 30s with a passion - personal or professional - for the work of the UN.