Rome, 25 July 2011: an emergency meeting is held at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to discuss the rapidly deteriorating conditions in the Horn of Africa. For the past two years, a severe lack of rain has afflicted Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania, and Uganda, and for 80% of the population who rely on agriculture as their main source of food and income, survival has become a daily battle.

While drought is a primary driver of the crisis, other forces are exacerbating the situation, such as high local cereal prices, excessive livestock mortality, and restricted humanitarian access. Most importantly though, conflict has been both a cause and an effect of food insecurity in the region, and cannot be ignored when developing strategies to prevent widespread starvation.

At the emergency meeting in Rome, Jacques Diouf, Director General of FAO, drew attention to the urgent need to restore stability: “it is essential to achieve peace so that people and livestock can move within countries and across borders to save lives and to preserve the foundations of food and nutrition security.”

It is no coincidence then that Somalia, a country which has experienced war on and off for 20 years, is bearing the brunt of the crisis, with famine declared in five areas. ‘Famine’ is a specific term applied to situations where there is a severe lack of food access for large populations, where acute malnutrition rates exceed 30% of the population, and where the crude death rate exceeds two people per 10,000 per day.

In the Somali territories of Bakool and Lower Shabelle, acute malnutrition tops 50% and death rates exceed six per 10,000 per day. The Islamist extremist group, al-Shabaab, which controls these areas, has banned organisations like the UN World Food Programme from entering, putting some 3.5 million people at risk of starving to death. The peace and security situation in Somalia is greatly affecting how and where aid is being delivered, and political instability is preventing relief from reaching those who are suffering the most.

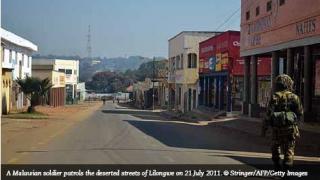

Some members of the international community have criticised the UN Security Council for not taking concerted action to stabilise the situation in Somalia before the crisis erupted. In 2009, plans for a UN peacekeeping mission in the country, reportedly put forward by the US, were rejected by other members of the Council on the grounds that there wasn’t enough ‘peace to keep’. Instead, the UN has backed the African Union Mission in Somalia. While AMISOM’s presence has helped vital aid to be delivered, its effectiveness has been hampered by resources. Only 9,200 peacekeepers of the 20,000 promised have been sent to the country. All are based in Mogadishu, the capital city.

In early August, al-Shabaab withdrew from Mogadishu, easing the situation somewhat. But the group still controls swathes of territory. Experts believe that al-Shabaab has been experiencing internal divisions as a result of the ‘Arab Awakening’ and the drought, and that the Security Council should have seized this opportunity to bring peace to the insurgent-controlled areas. Now, it is hard to do anything but relief work, and there are speculations that al-Shabaab will use the unstable conditions caused by the famine to regain power.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, a quarter of the Somali popuation is displaced. Some are fleeing the conflict-ridden al-Shabaab areas to Mogadishu, where the Badbaado Camp opened on 12 July. It already houses more than 20,000 and lies just 400m from the ‘frontline’ between pro-government forces and the insurgents. The weak Transitional Federal Government controls only parts of the capital city.

Others are seeking refuge in the neighbouring states of Kenya and Ethiopia, both of which are suffering from the same situation. Refugee camps have exceeded their maximum capacity and each day the security situation become harder to manage. An estimated 1,500 Somali refugees a day have been arriving in Kenya’s Dadaab camp.

In the Horn of Africa, peace and security and food security are unequivocally interdependent: in order for sustainable food production to take root and thrive there must be political stability, and when people have secure sources of sustenance conflict invariably decreases. The people living in Somalia are suffering disproportionately because they lack both personal and nutritional security. The international community must acknowledge this mutual relationship and work to devise a cohesive strategy that addresses both these problems.

Madelyn recently finished her MSc in Regional and Urban Planning at the London School of Economics and is currently a Programme Development Intern at UNA-UK.