On 9 July 2011, after over two decades of civil war, the Republic of South Sudan became the 193rd UN member state. Celebrations took place across the new republic, from farming communities in Equatoria to livestock herders in Upper Nile, as well as diaspora communities around the world. People spoke emotionally about their pride in living to see independence and at long last having their own identity.

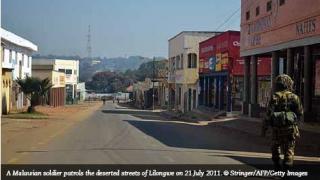

But from what position will this new republic start? Its independence has come at a high human price, and recent instability in Abyei and Southern Kordofan has again strained relations with the North. The day before independence was declared, the UN Security Council established a peacekeeping mission for South Sudan. Earlier this year, it also created an interim security force in Abyei to monitor flashpoints between the North and South.

South Sudan begins life as one of the world's poorest and least-developed countries. The UN Population Fund (UNFPA) reports that South Sudan has the highest rate of pregnancy-related deaths: over 2,000 women die for every 100,000 births. The equivalent figure in the UK is 11 per 100,000, while in north Sudan it is 638.

South Sudan also has one of the weakest education systems. The UN Children's Fund (UNICEF) estimates that more than 80% of women and 60% of men are illiterate, and despite major efforts to increase enrolment, over 50% of primary school-age children are still not in school. The figure rises to 63% for girls, who, according to UNFPA, are more likely to die in childbirth than they are to finish primary school.

What South Sudan does have is the goodwill of almost every other country in the world, and commitments from major international donors, including UN agencies, the European Union and the World Bank; and from bilateral donors such as the US, UK, Norway and Japan. But, as donor representatives in the South Sudanese capital Juba admit, commitments are not always acted on.

For example, of the $91.9m committed to the education system in 2005, just $7.7m had been allocated two years later. A recent evaluation by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development of the Multi-Donor Trust Fund - which has managed a significant proportion of aid funding to South Sudan - noted its slowness in disbursement and a lack of results. This is due in part to the fiduciary rules and regulations applied by the Fund. These were meant to guard against corruption but have proved too strict to work in a fragile state. So one question that donors must address now is how to be more flexible in distributing funds while avoiding their misuse.

In the longer term, South Sudan has the potential to be less dependent on aid than most developing countries, especially those in Africa: it has the benefits (some would say curse) of oil. Sudan's proven reserves have been estimated at 5bn barrels, most of which are located in what is now South Sudan, although the borders are still subject to dispute.

In 2007, 95% of the then-Government of South Sudan's (GOSS) revenues came from oil and petroleum. Between 2005 and independence, there were arrangements under which 75% of the oil wealth originating in the South was to be shared equally with the North. However, these arrangements did not take account of oil from the North, and there were repeated complaints that the South's oil was not being shared equally.

In the 1970s, Western companies such as Chevron, Total and Royal Dutch Shell pioneered the development of oil exploration in Sudan. Most pulled out in the 1980s. Over the past 10 to 15 years, they have been largely replaced by oil corporations from Asia, such as the China National Petroleum Corporation, India's Oil and Natural Gas Corporation and Malaysia's Petronas. These companies are generally viewed by Southerners as having supported north Sudan during the civil war and although their governments have made approaches to the GOSS since 2004, there is likely to be a review of agreements. Will the South Sudanese government turn to Western or remain with Eastern corporations? And will these decisions be based on the balance between Western aid and Eastern trade? Whichever direction it turns, one major problem South Sudan will face is that almost all of the oil and petroleum infrastructure, refineries, pipelines and export terminals are located in the North. To develop its own is likely to come at the expense of investing in health and education. South Sudan's success, therefore, remains heavily dependent on good relations with the North, and the choices it makes on whether to turn East, West or perhaps both ways.

Michael Brophy is Director of the Africa Educational Trust. For more information, visit www.africaeducationaltrust.org.