On 26 May 2011, Alain Le Roy, the outgoing UN Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, visited the UK to participate in an event to mark the International Day of UN Peacekeepers, jointly organised by UNA Westminster branch, UNA-UK, and the Royal United Services Institute.

Prior to the event, New World secured an interview with Mr Le Roy in which he calls on the UK to do more to support missions and reveals the one thing that would immediately improve the effectiveness of peacekeeping.

UN peacekeepers play a vital role in protecting civilians all over the world. But with 100,000 personnel spread over five continents and a budget of less than $8bn, is peacekeeping largely symbolic?

Oh no no. If you compare this figure to the cost of the war in Afghanistan - over $100bn a year, and to global military spending - more than $1 trillion a year, it seems very limited, and even so, member states appear to find it difficult to fund. But our budget is certainly enough to allow us to make a difference.

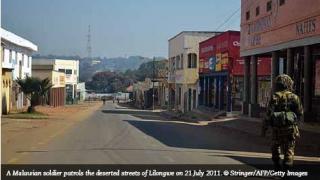

There are actually 120,000 peacekeepers worldwide - in addition to military and police, we have some 20,000 civilian officers because tasks like protecting human rights, assisting with reintegration and organising elections are increasingly part of our multidimensional operations. We are in 14 countries and in all of them we play a crucial role. Think of Sudan, Haiti, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) - our presence is extremely important for the protection of hundreds of thousands of people every day.

Shortly after you took up your post in 2008, you said in an interview that peacekeeping may have reached its limits, echoing the seminal report produced in 2000 by Lakhdar Brahimi in the wake of Rwanda, Somalia and Bosnia. Is this report still relevant?

Absolutely. The Brahimi report remains the report on peacekeeping and we have used it as a basis for our current reflections. It sets out clearly what remain the three fundamental principles of peacekeeping: consent of the main parties, impartiality, and the use of force only in self-defence. But the Brahimi report was issued in 2000, when we had just 25,000 peacekeepers. Today we have 120,000 peacekeepers deployed in much more complex situations. Our missions are multi-faceted and have higher civilian components, so there is a need to revisit our strategies.

Our New Horizon initiative, launched in 2009, aims to assess the major policy and strategy dilemmas facing UN peacekeeping. We have produced a paper with reflections from my department (peacekeeping operations) and from the department of field support, and this document is on the table everywhere, in the Security Council, General Assembly committees, and so on. All the key themes raised - protecting civilians, peacebuilding, field support - are being discussed and we have been able to reach more consensual decisions in this way. The process is not complete but we have started it and are regularly producing progress reports.

You mentioned the 'use of force only in self-defence'. Earlier this year, in Côte d'Ivoire, the UN was criticised for being too robust. Do you think it overstepped its mark?

Actually, Côte d'Ivoire is an example of the Brahimi report in action - the international community wanted to avoid the failures of the 1990s. We did not want another Srebrenica. So despite being harassed and shot at on many occasions, the mission did not for a single minute consider leaving. We stood firm and acted in complete conformity with the mandate adopted by the UN Security Council on 13 March, which permitted the targeting of heavy weapons to prevent them being used on civilians. This is what we did, and when I briefed the Council, everyone recognised that we acted within our mandate. Yes, it was robust, but I was very pleased to hear Navi Pillay, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court say that our actions had helped to prevent a situation like we had in 1994 in Rwanda.

In contrast to Côte d'Ivoire, the UN is sometimes accused of doing too little in the DRC. Is the mission making a difference or is it more of a 'mission impossible'?

Of course, the situation is still very serious in the DRC. People are being killed and women raped despite our presence. But if we were to leave, those numbers would be multiplied by 10 or even 100. There are just 18,000 UN peacekeepers in the DRC, Africa's third largest country. The Kivu regions alone have populations of some 10 million. So just like a local police force is unable to prevent all crimes, we too cannot protect everyone.

That said, every death, every rape is a failure and we try to draw lessons from that. We now have 96 bases in eastern DRC to be as close as possible to the women at risk. We provide the communities with means of communication to contact the bases for any emergency, and we regularly send joint protection teams that include human rights and child protection officers. We have developed strategies that do not exist anywhere in the world; we are the pioneers in protecting civilians in this environment. While we don't succeed 100%, everybody who has been to the DRC realises how important our presence is.

In 2005, world leaders accepted their 'responsibility to protect' (R2P) civilians whose state is unwilling or unable to do so. Do you believe there is a corresponding personal responsibility for UN peacekeepers on the ground, even if their mandate limits what they can do?

The Brahimi report puts it very clearly: when a civilian is under threat, we must not stand by and do nothing. Peacekeeping mandates have not to date mentioned 'R2P' (although it was mentioned for the first time in a Security Council resolution on Libya earlier this year), rather, they refer to the protection of civilians under imminent threat. This is the mandate we get for most missions and this is what we are trying to do every day.

Which of the current peacekeeping missions do you think will become more challenging this year?

We are speaking on 26 May and at this time I would say Sudan. The violence in Abyei is absolutely unacceptable and especially worrying as we are preparing for a new mission starting on 9 July in South Sudan. That area will require a lot of our attention in the coming months. Equally, our mission in Lebanon will need careful monitoring given that nobody knows how the situation in the wider Middle East will unfold.

You are in London to mark the International Day of UN Peacekeepers. Is there something particular you have been calling on the UK to do?

Yes, four things. First, to continue the great political support we get from the UK in the Security Council. The UK is always supportive of our operations and currently the third biggest funder of UN peacekeeping. Second, we hope that the UK might be willing to increase its participation in terms of troops. At present the UK has fewer than 300 troops serving in missions. In 1995, it was 10,000. I fully understand that the UK is overstretched in Afghanistan and elsewhere, but perhaps it could consider raising its peacekeeping deployment to, say, a thousand.

Third, if this is not possible, the UK could still help us to enhance our capabilities. This could take the form of training; other states, like the US and France train, equip and sometimes even airlift peacekeeping troops from other countries, or helping us to get the equipment we need. We have a serious lack of military helicopters and, though I know the UK is also experiencing similar shortfalls, it might be able to help persuade others, notably the European Union (EU), to contribute.

And fourth, the UK could help enormously by sharing its expertise in rapid deployment capability. It would be really useful, for instance, if the UK could work within the EU framework on the EU 'battle groups' which could provide the rapid reaction capability that we lack at present.

What is the one thing that would make UN peacekeeping more effective?

Very easy: we need more military helicopters. When we were in Darfur, we had to protect about two million internally displaced people. The DRC, as I said earlier, is a huge terrain. What we urgently need is transport capability - helicopters in particular - and this is what we lack the most.

What would you say to members of the British public who, given the current economic situation, might not think that support for UN peacekeeping is important?

I would say to them: imagine what the world would be like without peacekeeping. Think of Sudan, where we were able recently to preside over a largely peaceful independence referendum. Think of the DRC, where some four million have died: can we afford to stand by? The UK rightly took the decision to preserve its development aid spending in the interests of creating a more stable world. Peacekeeping is a key element of this - our presence in the DRC, South Sudan and elsewhere is contributing to increased stability without which UK national interest could well be threatened. US President Obama has said that UN peacekeepers are in those areas where countries like the US and UK cannot be, helping to create a more peaceful and secure world for us all.

What would you most like to have achieved by the end of your term in August 2011?

Two things: first, to ensure that UN peacekeeping remains an effective tool at the disposal of the international community. What we do is unique -we alone have a combination of military and civilian officers from around the world and we alone have the legitimacy to save civilians and protect countries from relapsing into conflict.

Second, I would like to see us continue to protect civilians at risk. We are not perfect but compared to the 1990s, I believe that UN peacekeeping has dramatically improved. We want to be even more effective for our stakeholders, which include some of the world's most vulnerable people.

And lastly, why is it important for us to have a day dedicated to UN peacekeepers?

Each time I visit a mission I am struck by the extraordinary dedication and courage of our staff and officers who risk their lives to protect others. Commemorations are one small way in which we can pay tribute to them. I encourage everyone, the media and those who are eager to criticise us, to visit our peacekeepers and see for themselves the fantastic job that they are doing.