This article is based on a paper prepared for a conference on 'Dag Hammarskjöld, the United Nations, and the End of Empire' organised by UNA Westminster branch on 2 September 2011

'Sit on the ground and talk to people. That's the most important thing.'

It was not a social anthropologist who provided this advice. Rather, this was the answer given by Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary-General of the United Nations, when asked over dinner by his friend John Steinbeck what would matter most during a world tour. He had followed a similar approach (though not necessarily sitting on the ground) during a five-week trip through Africa. The journey, from 22 December 1959 to the end of January 1960, took him to more than 20 countries on the continent, over which the 'winds of change' had begun to blow.

Upon his return on 31 January, he declared: "I would say that this experience [...] makes me less inclined than ever to generalise, to say this or that about Africa or this or that about Africans, because just as there is very much in common, especially the aspirations, there is also an enormous diversity of problems, of attitudes, and of traditions. In such a way, the journey makes me both a little bit wiser and a lot more humble."

In a subsequent press conference, Hammarskjöld elaborated on the approach he had outlined to his friend Steinbeck:

"You can say that to stay in a country one night or two nights cannot give much of an experience. Well, first of all, it can. It can because, if you break through the walls and if you have the necessary background knowledge, even a talk of one hour can tell you more than volumes [...] It is not in particular what you can learn in this or that city or from this or that man that gives you valuable understanding of the situation. It is what he says and what you see in one city seen in the light of what you have heard others say and what you have seen in other cities."

The trip attested to his general mindset and practice of seeking dialogue with others to explore the common ground of humanity. For Hammarskjöld, the United Nations was "an expression of our will to find a synthesis between the nation and the world". When a journalist at the press conference asked whether the ideological trends in Africa stem from the inner realities facing African life today or whether they reflect the often repeated clichés of foreign ideology, Hammarskjöld's clarification left no doubt:

"I do not think that the rights of man is a foreign ideology to any people and that, I think, is the key to the whole ideological structure in Africa at present. It may be that the most eloquent and the most revolutionary expressions of the rights of man are to be found in Western philosophers and Western thinking, but that certainly does not make the idea a Western idea imposed on anybody."

The fundamental ethics that were his moral compass as a global leader guided his engagement not only with African realities. His role as the highest international civil servant was based on values that were permeated by a notion of solidarity. On 26 January 1960, towards the end of his African journey, he declared at the second session of the Economic Commission of Africa in Tangier:

"Partnership and solidarity are the foundations of the United Nations and it is in order to translate these principles into practical measures of economic cooperation that we are gathered today in this hall [...] The emergence of Africa on the world scene, more than any other single phenomenon, has forced us to reappraise and rethink the nature of relationships among peoples at different stages of development, and the conditions of a new synthesis making room for an accelerated growth and development of Africa."

Hammarskjöld then reminded his audience that nobody should forget that colonisation "reflected a basic approach which may have been well-founded in certain limited respects, but which often mirrored false claims, particularly when it touched on spiritual development". Applied generally he concluded, it was untenable.

Commenting on the Western perspectives of the early 20th century, Hammarskjöld found it striking"how much they did not see and did not hear, and how even their most positive attempts at entering into a world of different thoughts and emotions were colored by an unthinking, self-assured superiority".

For Hammarskjöld, the richest satisfaction lay in meeting different spiritual traditions and their representatives, provided one approached them "on an equal footing and with a common future goal in mind". He was confident that this approach would ensure progress "in the direction of a human community which, while retaining the special character of individuals and groups, has made use of what the various branches of the family of man have attained along different paths over thousands of years".

He clearly dismissed any claims to superiority over others based on any kind of naturalist concept of dominance rooted in supposed biological advancement and also questioned the legitimacy sought by dominant classes to justify their privileges:

"[We] live in a world where, no more internationally than nationally, any distinct group can claim superiority in mental gifts and potentialities of development [...] Those democratic ideals which demand equal opportunities for all should be applied also to peoples and races [...] no nation or group of nations can base its future on a claim of supremacy."

Hammarskjöld also had a strong sense of the need for economic justice. In his last address to ECOSOC, he linked the principles of national sovereignty to the belief that international solidarity and social consciousness must go hand in hand by: "accepting as a basic postulate the existence of a world community for which all nations share a common responsibility [...] to reduce the disparities in levels of living between nations, a responsibility parallel to that accepted earlier for greater economic and social equality within nations."

This corresponds with his earlier and continued emphasis on the need to address the economic imbalances inherent in the existing world order. As he stressed in an address as early as February 1956:

"The main trouble with the Economic and Social Council at present is that, in public opinion and in practice, the Council has not been given the place it should have in the hierarchy of the main organs of the United Nations. I guess that we are all agreed that economic and social problems should rank equal with political problems. In fact, sometimes I feel that they should, if anything, have priority."

He testified further to his awareness of the needs for global economic justice only a few months later in his opening statement during a debate on the world economic situation in ECOSOC. In his remarks, he bemoaned:

"The absence of a framework of international policy that compels the underdeveloped countries each to seek its own salvation in its own way without reference to wider horizons. How often have we not heard the voices of those who bewail the fact that this underdeveloped country is moving along the slippery path to autarky, that that country is neglecting its exports, whether agricultural or mineral, or that yet a third country is manipulating its exchange rates in a manner contrary to the letter and spirit of the Bretton Woods agreements? And yet how many of those who belabor the underdeveloped countries in this fashion have given adequate thought to the structure of world economic relationships which has forced these countries into unorthodox patterns of behavior?"

The introduction to the 16th annual report of the United Nations became Hammarskjöld's last programmatic statement. Submitted a month before his untimely death, it underlined his firm belief in the equality of peoples and societies, as different from each other as these might be perceived to be:

"In the Preamble to the Charter, Member nations have reaffirmed their faith 'in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small,' a principle which also has found many other expressions in the Charter. Thus, it restates the basic democratic principle of equal political rights, independently of the position of the individual or of the Member country in respect of its strength, as determined by territory, population or wealth. The words just quoted must, however, be considered as going further and imply an endorsement as well of a right to equal economic opportunities."

Importantly, Hammarskjöld once again does not content himself with proclaiming noble postulates by making lofty reference to an abstract equality. As a trained economist, he never lost sight of the socioeconomic dimensions of inequality. It is therefore no coincidence that he returns to stress the right to equal economic opportunities:

"So as to avoid any misunderstanding, the Charter directly states that the basic democratic principles are applicable to nations 'large and small' and to individuals without distinction 'as to race, sex, language and religion,' qualifications that obviously could be extended to cover other criteria such as, for example, those of an ideological character which have been used or may be used as a basis for political or economic discrimination [...] The demand for equal economic opportunities has, likewise, been – and remains – of specific significance in relation to those very countries which have more recently entered the international arena as new states. This is natural in view of the fact that, mostly, they have been in an unfavourable economic position, which is reflected in a much lower per capita income, rate of capital supply, and degree of technical development, while their political independence and sovereignty require a fair measure of economic stability and economic possibilities in order to gain substance and full viability."

In his last words to his staff, Hammarskjöld reiterated again one of his fundamental principles: "if the Secretariat is regarded as truly international, and its individual members as owing no allegiance to any national government, then the Secretariat may develop as an instrument for the preservation of peace and security of increasing significance and responsibilities."

Hammarskjöld's steadfastness when navigating through the manifold international interests vested in the Congo and seeking to influence his policies remain exemplary. Despite all efforts he resisted the pressure from the hegemonic states both in the East and the West to give in. When the Soviet government and its allies campaigned for Hammarskjöld's resignation on the grounds that he was a lackey of Western imperialism, he continued to stay on course not only delivered his famous speech in the General Assembly in early October 1960. He continued to stay on course also in the subsequent debates in the Security Council.

Refuting the allegations, he stated on 13 February 1961 in another response in the Security Council to the continued demands for his resignation over the policy in the Congo:

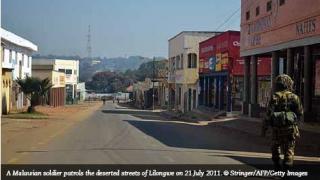

"For seven or eight months, through efforts far beyond the imagination of those who founded this Organization, it has tried to counter tendencies to introduce the Big-Power conflict into Africa and put the young African countries under the shadow of the cold war. It has done so with great risks and against heavy odds. It has done so at the cost of very great personal sacrifices for a great number of people. In the beginning the effort was successful, and I do not now hesitate to say that on more than one occasion the drift into a war with foreign-power intervention of the Korean or Spanish type was avoided only thanks to the work done by the Organization, basing itself on African solidarity.

We effectively countered efforts from all sides to make the Congo a happy hunting ground for national interests. To be a roadblock to such efforts is to make yourself the target of attacks from all those who find their plans thwarted. (...) From both sides the main accusation was a lack of objectivity. The historian will undoubtedly find in this balance of accusations the very evidence of that objectivity we were accused of lacking, but also of the fact that very many Member nations have not yet accepted the limits put on their national ambitions by the very existence of the United Nations and by the membership of that Organisation."

His even-handedness towards the big powers is documented by another incidence, shared by Sture Linnér (1917-2010) with an audience attending his presentation at the annual Dag Hammarskjöld Lecture in October 2007 in Uppsala. Linnér was at the time of Hammarskjöld's death Under-Secretary-General in charge of the UN mission in the Congo. In July 1961 President JF Kennedy tried to intervene directly.

Afraid of Antoine Gizenga coming to power (he was then campaigning for election as Prime Minister and suspected of representing Soviet interests), Kennedy demanded that the UN should prevent Gizenga from seizing office. If not, he threatened, the United States and other Western powers might withdraw their support to the UN. Reportedly, Hammarskjöld in a phone conversation with Linnér dismissed this unveiled threat with the following words: "I do not intend to give way to any pressure, be it from the East or the West; we shall sink or swim. Continue to follow the line you find to be in accordance with the UN Charter."

Sture Linnér ended his Dag Hammarskjöld Lecture with the conclusion: The Congo crisis could easily have provoked armed conflicts in other parts of Africa, even led to a world war. It was Dag Hammarskjöld and no one else who prevented that. And it is certain that for a suffering people he came to be seen as a model; he brought light into the heart of darkness.

Dag Hammarskjöld's ethics, his concept of solidarity, his sense of fundamental universal values and human rights, his respect for the multitude of identities within the human family and his responsibility as the world's highest international civil servant to assume global leadership, set standards that have to this day lost none of their value and relevance.

The way he defined and executed his duties, exemplified by his actions on the continent of Africa, can be qualified as an act of international solidarity of a nature that is all too often missing today.

Henning Melber is Executive Director of The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation in Uppsala, Sweden and research fellow with the Department of Political Sciences at the University of Pretoria. For more information, visit http://www.dhf.uu.se/