Natalie Samarasinghe, Executive Director of UNA-UK, explores the gaps, discrepancies and challenges in refugee protection.

Issuing false documents, bribing officials and smuggling babies in packages – today, such actions might rightly be criticised as people trafficking but during the Second World War this is how Oskar Schindler, Irena Sendler, Raoul Wallenberg and others saved thousands of Jewish lives.

Drafted in the years following the war, the 1951 UN Refugee Convention recognised that it may sometimes be necessary for those fleeing persecution to enter a country without authorisation, stating that countries “shall not impose penalties, on account of their illegal entry or presence”. This obligation has been progressively eroded, at least in the West, through the concepts of “illegal immigrants” and “bogus asylum seekers”. These labels shift the focus from what someone has had to endure to how they entered a country, and imply criminalisation of the person themselves, often with serious consequences for their ability to access protection.

Destination matters

Although 145 states are party to the Refugee Convention, there are huge differences in how refugees are treated and whether they are even classified as such. In developing countries, which host the vast majority of refugees, admission tends to be granted on a group basis, leading, for example, to the mass influx of refugees from Syria into Lebanon or Afghanistan into Pakistan (neither of which, incidentally, has ratified the Convention). In low-income and fragile countries, scarce resources often mean refugees are held in camps rather than integrated into communities, and their rights to housing, education, health care and other necessities can be limited.

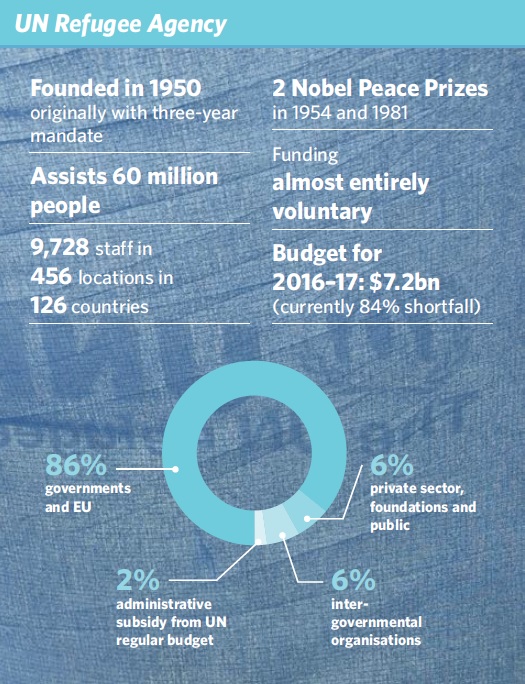

There are, of course, exceptions. In 2014, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) praised Tanzania’s decision to grant citizenship to 162,156 former Burundian refugees – the largest group in the Agency’s history to receive naturalisation after decades in exile.

Fortress Europe

By contrast in wealthier states, those accorded refugee status often enjoy citizens’ rights, at least after some time, but few are granted entry and even fewer make it through the gruelling process. Those seeking to claim asylum generally face lengthy and complex application procedures. In the UK this can include months (in some cases years) in detention centres while claims are being processed – a practice opposed by UNHCR. Those fleeing conflict zones but unable to prove individual persecution can find themselves turned away, as European states tend towards individualised, rather than prima facie, admission policies.

Again, there are notable exceptions: Germany’s acceptance of a million refugees last year, for instance. But the broad trend has been towards a curtailment of refugee rights through a process designed to make it increasingly difficult to gain refugee status.

The EU–Turkey agreement is the latest manifestation of this trend. While UNA-UK welcomes attempts to manage the situation – long overdue given the dire warnings that UNHCR issued in the lead-up to the crisis – we share widespread concerns about its potential to lead to blanket expulsions and unsafe deportations, especially in light of the lack of capacity to implement the policy in a manner that protects those affected.

More “illegals”?

The current displacement crisis – the biggest since records began – is not likely to abate any time soon. If Syria, the largest source of refugees, is excluded,the underlying trend remains and will only be exacerbated by challenges such as climate change. Unless new tools and approaches are adopted, this future landscape is likely to make more people “illegal”.

With numbers on the rise, it is time for states – particularly wealthier countries – to ensure that refugees are able to exercise their right to claim asylum without having to put their lives in the hands of smugglers. There must also be greater support for the developing countries that host the vast majority of refugees.

Closing the gaps

The 1951 Convention does not explicitly address the issue of civilians caught up in generalised situations of violence, unless they belong to a particular group being persecuted. While UNHCR’s position is that people fleeing indiscriminate effects of conflict should be considered refugees if their government is unable or unwilling to protect them, states vary considerably in their interpretation.

Africa and Latin America have adopted instruments recognising such people as refugees. In Europe, there is much less consistency, with some states insisting on proof of individual persecution, others setting up limited schemes for particular nationalities and others taking a broader view, particularly for Syrians. Greater harmonisation is sorely needed.

We must also address disaster displacement which, as Walter Kälin points out on page 12, must be integrated into humanitarian, climate and disaster risk reduction frameworks. In the interim, “asylum” may offer another route to protection. It is already applied as a response to situations that do not fit the traditional refugee paradigm, particularly by countries in Europe where “leave to remain” is sometimes granted rather than refugee status.

Finally, we must address mixed movements of people. Politicians have repeatedly questioned whether those arriving in Europe are ‘refugees’ or ‘migrants’, fuelling notions of those ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ of support. Refugees still dominate the numbers – UNHCR has stated that over 90 per cent of those arriving in Greece in 2015 and the year to date are from the top 10 refugee-producing countries. But it is undeniable that this is a mixed movement of people that must be managed accordingly, with fair processes for refugees and migrants alike.

This means accepting that migration is a reality, an integral part of global development and an opportunity as well as a challenge. It means looking at the facts not the headlines. Far from being out of control, it is surprising that migration is not higher than it is: in 2015, just 3.3 per cent of the world’s population lived outside their country of origin.

Above all, it means treating refugees and migrants as people, not statistics, not “illegals”, not problems, but humans who have, through choice or necessity, crossed a border – surely a right that none of us would be willing to give up.

Photo: Somali mother and baby inside UNHCR tent in Ethiopia – the world's fifth largest refugee-hosting country and the largest in sub-Saharan Africa in absolute and relative terms. Copyright UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe