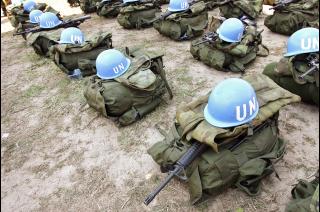

Despite not being expressly mentioned in the UN Charter, UN peacekeeping has become integral to the UN’s stated mission to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war”. UN peacekeepers operate in some of the most fraught and violent regions across the globe.

A consequence of the ad-hoc manner in which peacekeeping was established is that, to this day, it sits - sometimes awkwardly - between three sources of power and control: the member states of the UN Security Council (UNSC) who establish the mission and provide it, via a mandate, with its tasks and rules of engagement; the individual nations (known as Troop Contributing Countries or TCCs) that provide troops themselves and continue to exert command and discipline over them; and the Department for Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), civil servants answerable to the UN Secretary General, tasked with managing and coordinating the work of the UN missions.

Peacekeeping has a strong track record. Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire, Timor-Leste, and Liberia, among others, could have had a far bloodier past, and no future, had it not been for the timely and effective intervention of blue-helmeted troops. There have been colossal failures: failures to deploy (as in Rwanda), failures to act once deployed (as at Srebrenica), failures to operate safely (a cause of the cholera outbreak in Haiti) and failures to prevent abuse (most notoriously when it comes to sexual exploitation and abuse). But undoubtedly the world is a safer and a better place as a result of UN peacekeeping.

Since the first deployment of military observers to the Middle East in 1948, over 128 countries have contributed personnel to 69 UN-mandated peacekeeping operations – of which 16 are active as of 2 December 2014. These missions are staffed by over 122,969 personnel, and have a combined budget of just over $7 billion. Peacekeeping missions can range from the monitoring of borders (as UNIFIL does between Israel and Lebanon), to providing security and policing (MINUSTAH in Haiti), to undertaking counter-insurgency operations (MINUSMA in Mali), to providing civilian and political support (as UNSMIL does in Libya) – and protecting civilians (UNAMID in Darfur, MINUSCA in the Central African Republic, and MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

Current challenges and reform

The nature of UN peacekeeping is changing considerably. The traditional role of a peacekeeper was to observe the ceasefire line in a frozen conflict, and in a minority of missions (Cyprus and South Lebanon) that is still the case. An emergent norm from subsequent generations of peacekeeping missions was that the role of a peacekeeper was to extend the legitimate authority of the state. But in some of the increasingly fragmented and fragile conflicts where peacekeepers currently operate, the state cannot be thought of as a singular entity, and its legitimacy is not beyond question. Nowadays the role of the peacekeeper is often to protect civilians, including by the use of force, in situations where there is no peace to keep. And despite the fact that in principle, peacekeeping always happens via the consent of the host government, in extremis the state itself can be seen as a hostile actor.

The three principles that guide peacekeeping – consent of the host state, impartiality and non-use of force (except in self-defence or defence of the mandate) are evolving in parallel with these new challenges. Peace operations today are ‘multidimensional’, made up of military, police and civilian contingents. Consent for UN peacekeeper deployment no longer requires an active peace treaty or agreement; and peacekeepers now frequently operate in sites of active conflict with robust mandates to protect civilians.

Many modern conflicts are low-intensity and irregular, with a lack of formal armies and with various competing groups. It is unfeasible for peacekeepers to maintain the traditional no-man’s land between opposing forces; UN peacekeepers now have to take a more proactive role. With this comes increased risk for UN forces – while they remain impartial they do not remain neutral, and taking action to protect civilians has made them targets for attacks. Casualty rates have steadily increased, and with this heightened risk to their soldiers many troop contributing countries have demanded more say in the mandates and tasks of peacekeepers.

Major reform of contemporary UN peacekeeping began in 2000 with the Brahimi Report, which sought to incorporate lessons learned in Srebrenica and Rwanda. This reform process has continued throughout the 2000s, with the Capstone Doctrine and New Horizon papers building on Brahimi’s work, and improving the UN’s ability to respond to modern conflicts. More recently, in October 2014 the UN announced a new, comprehensive inquiry into peacekeeping operations and special political missions, led by a panel of experts from both within the UN and outside it.

The UK and UN Peacekeeping

There are three aspects to UK involvement in UN peacekeeping: in the Security Council, establishing peacekeeping mandates; providing funding for operations; contributing troops.

The UK plays a central role on the Security Council, and is the country responsible for drafting resolutions on peacekeeping, the protection of civilians, the Women, Peace and Security Agenda and country-cases such as Somalia, Darfur and Cyprus.

In addition to this involvement in high-level decision-making, the UK is a major financial donor to peacekeeping operations. The fifth largest contributor, the UK provides 6.68% of the UN’s overall budget for peacekeeping.

With respect to troop contributions however, the UK arguably falls short. The UK provided only 286 troops (most of whom serve in Cyprus, a long-term and relatively quiet mission, and of which only 18 are women), 5 police officers and no military advisors, as well little military equipment. This places the UK 50th amongst peacekeeping contributors; a small country like Fiji provides more than double the personnel that the UK does, while a fellow permanent member of the Security Council, China, gives 2,183 personnel.

The UK has recently announced plans to nearly double this contribution with a deployment of 370 troops to Somalia and South Sudan. This is welcome news, however the total number of troops deployed remains relatively small.

UNA-UK’s Peacekeeping Programme

UNA-UK aims to increase awareness of UN peacekeeping in the UK and stimulate serious public discussion on the topic. With the drawdown in Afghanistan, the UK has large numbers of military personnel, equipment and expertise that could be redirected to vital peacekeeping work, in line with the UK’s long history of humanitarian action. With UN peacekeeping missions widely respected and largely regarded as the most legitimate and impartial type of intervention, this would also boost the UK’s international profile and influence.

There are a number of ways for the UK to become further involved in UN peacekeeping, including:

Providing personnel

- Specialist support, particularly gender specialists, engineers, medics and military advisors

- Leading the way in contributing female forces

- Police or policing advisors

Logistical support

- Helicopters and transport aircraft to improve airlift capacity

- Pilots trained to operate in difficult conditions

State- and UN-capacity building

- Improving support for strategic planning

- Providing training for troops, police and civilians within the UN and states

- Sharing best practice, and the lessons learnt from UK peacekeeping

For more information on UNA-UK's peacekeeping programme, please contact Fred Carver, Head of Policy, carver@una.org.uk, 020 7766 3445.