Floods, crop failure and desertifica- tion. The spread of diseases such as dengue and malaria. At least 14% of the world’s population exposed to heat- waves, 130 million people to drought and 270 million to water stress. More than five million excess deaths per year from extreme temperatures alone.

Some 570 cities – including Miami, Rio, The Hague, Alexandria, Hong Kong and Osaka – in danger from rising sea levels, risking 800 million lives and $1 trillion in economic damage. Over 140 million people displaced within their borders each year. Climate pressures fuelling conflict, crime and extremism.

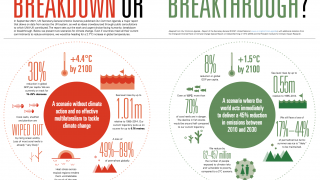

This is the best-case scenario we can hope for now. It is predicated on radical and immediate action to slash emissions, reach net zero by 2050 and limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C by 2100. Six years ago at the UN climate conference in France, small island states pushed for this target to be included in the Paris Agreement. Their pleas went unheeded. It is listed only as an aspiration.

Since then, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that if we overshoot by just half a degree – the actual target agreed by governments in 2015 – an extra 62 to 457 million people will be at risk. And even that scenario remains off track. Our current trajectory puts us on course for 2.7°C heating if – and only if – everysingle country meets every commitment it has made. If they do not, we may have to contend with large swathes of our world becoming uninhabitable (see The Facts for more statistics and sources).

The latest IPCC report, released in August 2021, warns that we have already changed the climate in ways that cannot be remedied for centuries, maybe millennia. As we note in our Briefing, whatever we do now, the ocean will continue to warm; glaciers will continue to melt.

I am not sure how to prepare my daughters for their future. Their privilege means they are not yet suffering directly, but it is only a matter of time.

Wildfires and heatwaves are no longer confined to “countries over there”. Political instability and disruption to food supply no longer seem like distant threats. Only the first half of the COVID-19 mantra applies: nobody is safe.

Indigenous and coastal communities face being wiped out. Entire countries could succumb to their “watery graves” as Abdulla Shahid eloquently warns. Those of us in the West already tolerate an obscene amount of suffering in poorer countries, as well as in our own communities.

If genocide is defined as deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about a group’s destruction, is our inaction tantamount to complicity? There is already momentum around expanding the definition of atrocities in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court to include ecocide (see Jojo Mehta).

The UN Human Rights Council recently recognised the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment and appointed a new Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Climate Change. The move will boost efforts across the world to strengthen environmental legislation, address gaps in protection and improve access to justice.

It will also provide an additional tool to challenge governments and companies that fail to take action on climate change, pollution and nature loss. At present, we struggle to deal with single incidents, such as the devastating oil spill off the coast of Sri Lanka earlier this year. We have yet to tackle the legal implications of sea level rise on maritime boundaries, let alone climate refugees.

And we are already grappling with violations of long-established rights – from the rights to life, housing, food and health to horrific attacks on environmental activists. According to Global Witness, last year was the most dangerous on record, with 227 activists killed. In South Africa, grandmother Fikile Ntshangase was murdered for campaigning against a coal mine. In India, journalist Shubham Mani Tripathi was shot after exposing sand-mining deals.

Over half of these attacks took place in just three countries – Colombia, Mexico and the Philippines, with indigenous peoples disproportionately represented. Only one killing took place in a rich country: Regan Russell was run over whilst protest-ing outside a slaughterhouse in Canada. But reports of intimidation and harassment abound in all regions. The right to protest is under threat in all parts of the world, including in the UK.

The climate crisis is fundamentally about human rights. While it demands that we break new ground in terms of legislation, it is rooted in our larger struggle against inequality and injustice.

This is evident from the uneven distribution of climate vulnerabilities within and between countries; from the historical responsibility for emissions that colonial powers bear; from the environmental crimes committed against the poor in authoritarian states (and in some democracies); and from the sheer inability of ordinary people to challenge the actions of multinational companies.

Given its existential nature, the climate emergency is arguably the great- est human rights challenge we face. We certainly need to treat it as such. A just transition to net zero isn’t an optional add-on to reducing emissions. It is essential if we are to make the case for drastic climate action to those who fear they will lose out – and to the politicians who hide behind them. It is essential if we are to avoid further suffering.

We need to stop tolerating unacceptable levels of harm in other parts of the world. We need to get serious about adaptation and burden sharing. We cannot pretend that aid absolves us from taking responsibility – whether that’s exporting our emissions to developing countries or expecting them to host the vast majority of displaced persons.

COP26 in Glasgow needs to deliver on emissions. But however tricky, broader legal and human rights issues also need to be tackled soon, whether that’s at the Stockholm+50 conference next year or through follow-up to the UN Secretary-General’s Our Common Agenda report (see the 10 feature).

We already have blood on our hands. How much more can we live with?

Photo: A woman carries supplies through a flooded street in Cap Haïtien. Credit: UN Photo/Logan Abassi