As the impacts of the climate emergency are felt by ever more people, what can we expect from the UN climate conference in Glasgow? Our briefing provides an overview of the latest IPCC report, the Paris Agreement and prospects for COP26.

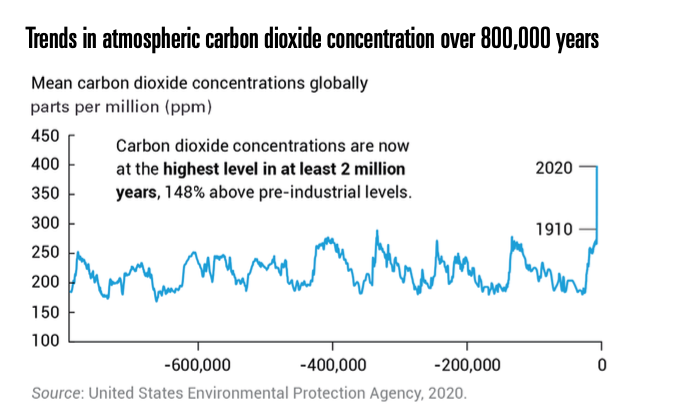

Human activity is changing the climate in unprecedented ways, some irreversible. This was the headline message of the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – the first major review of scientific evidence since 2013 and the Panel’s most emphatic statement that human activity is heating the atmosphere, ocean and land.

The report notes that global surface temperatures have increased by more than 1°C compared to pre-industrial levels. They have even breached 1.5°C – the aspirational target set out by the Paris Agreement on climate change – at certain points over the last years, such as during the 2016 El Niño.

These increases have affected many of our planetary support systems in ways that cannot be remedied for hundreds, if not thousands of years. The ocean will continue to warm and become more acidic. Glaciers and polar ice will continue to melt.

Extreme weather has already claimed millions of lives. The Lancet recently featured a study of 43 countries that attributed almost 10% of global deaths between 2000 and 2019 to excess mortality arising from abnormally hot or cold temperatures. The real figure is likely to be higher, when factors such as climate-fuelled conflict, disease and food disruption are taken into account.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres called the IPCC report “a code red for humanity”, and said we must halve emissions in the next few years to reach net zero by 2050.

This will be a priority for the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) conference to be held in Glasgow from 31 October to 12 November 2021.

From Rio to Paris

Almost 30 years since the UNFCCC was adopted in Rio de Janeiro, we are on course for 2.7°C heating by the end of the century – risking hundreds of millions of deaths and a drop of 15 to 20 per cent in global GDP per capita. Patricia Espinosa, UNFCCC Executive Secretary, has compared our situation to “walking into a minefield blindfolded”.

The UNFCCC was created in 1992 to prevent “dangerous” human interference with the climate system. It marked an important moment in terms of international recognition of climate change as a major global threat, and the need to stabilise greenhouse gas concentrations.

Given their past and current contributions to CO2 build-up, the Convention put the onus for emissions cuts on industrialised states. It also called for financial support to help developing countries mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change. A system of grants and loans has since been set up through the UNFCCC and is managed by the Global Environment Facility.

Today, there are 197 parties to the UNFCCC: the 193 UN Member States; the State of Palestine; the Cook Islands Islands and Niue; and the European Union. Every year, they conduct climate change negotiations – the largest being the Conference of Parties (COP) which is hosted by a different country each time.

In 1997, the third conference (COP3) adopted the Kyoto Protocol, which saw 37 rich countries take on binding emissions cuts. Developing countries argued that taking on limits would impede their development and be detrimental to their populations. They pushed for the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”, which holds that states’ differing contributions to environmental degradation, as well as their particular circumstances, must be taken into account when determining what action is expected of them. This remains a key consideration in negotiations today.

While Kyoto was significant as the first binding international emissions agreement, it had limited effect. While the (mostly European) states bound by its targets exceeded them, much of their success was due to the collapse of polluting industries, the outsourcing of emissions to developing countries where products are manufactured and, to a lesser extent, the 2008 financial crisis.

Meanwhile, emissions from emerging economies rose rapidly during this period, with China overtaking the US to become the world’s largest emitter in 2006–2007 (although its per capita emissions remain far lower). The US itself never ratified the Protocol and Canada withdrew at the end of the first Kyoto commitment period (2008–2012).

These tensions soured discussions on a successor to Kyoto. In 2009, the UN took a gamble by positioning that year’s COP in Copenhagen as the now-or-never moment for a new treaty. The conference ended in disarray, with a weak outcome document that was merely “noted” by the parties.

Paris in a nutshell

- Limit global temperature rise to 2°C, with 1.5°C included as an aspirational target (Article 2)

- Peak emissions and achieve carbon neutrality (Article 4)

- Binding commitments by all parties to define, implement and report on a Nationally Determined Contribution (Article 4)

- Conserve and enhance sinks and reservoirs of emissions, such as forests (Article 5)

- Voluntary cooperation among parties to allow for higher ambition and support sustainable development (Article 6)

- Enhance adaptive capacity and resilience, including through national adaptation plans (Article 7)

- Address loss and damage associated with climate change, including extreme weather events and slow onset events such as desertification (Article 8)

- Finance, technology and capacity-building support to developing countries (Articles 9, 10 and 11)

- Education, training, public awareness and access to information (Article 12)

- Transparency of implementation, including through self-reporting and and international technical expert review (Articles 13 and 15)

- A “global stocktake” to take place in 2023 and every five years thereafter (Article 14)

Subsequent meetings set their sights on 2015 for states to adopt “a protocol, another legal instrument, or an agreed outcome with legal force” that is applicable to all parties from 2020. Alongside this, there was a continued push to engage countries – in particular the largest emitters, developing as well as developed – in mitigation pledges.

Finally, at COP21 in Paris, parties to the UNFCCC reached a landmark agreement by which all countries agreed to take action on climate change. The Paris Agreement commits states to keeping global temperature rise to below 2°C. A number of states pushed for a lower target of 1.5°C, which is reflected in the document as an aspiration. The Agreement also aims to increase countries’ ability to deal with the impacts of climate change, including through financing and technology.

Unlike the Kyoto Protocol, the Agreement does not contain binding emissions cuts for states. Instead, it requires parties to put forward ‘nationally determined contributions’ (NDCs) that they must report on regularly. In addition, it provides for a global stocktake to assess collective progress. The first one will take place from 2021 to 2023.

The Agreement entered into force in 2016, after meeting the threshold of ratification by 55 countries that account for at least 55% of global emissions. As of 24 October 2021, only five of the 197 parties to the UNFCCC have not ratified it: Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Libya and Yemen. Earlier this month, Turkey became the last G20 country to ratify the Agreement. While the UNFCCC classifies Turkey as an industrialised nation, Turkish lawmakers were keen to stress they see themselves as a developing country.

Glasgow: Great expectations?

Hosted by the UK in partnership with Italy, COP26 was postponed in 2020 due to COVID-19. One year on, around 120 world leaders and 25,000 participants are expected to travel to Glasgow – although participation by civil society, especially from the Global South, is likely to be lower than usual (see Adriana Abdenur and Maiara Folly online).

Raising ambition will be a central objective – especially around keeping global temperature rise below 1.5°C and peaking emissions in the next few years. The UK Prime Minister has called for action on “coal, cars, cash and trees”, asking countries to accelerate the phase-out of coal and switch to electric vehicles, encourage investment in renewables and curtail deforestation. Common timeframes for emission-reduction commitments has also emerged as a key issue.

As the impacts of 1°C temperature rise are felt across the world, adaptation is likely to be more prominent than at previous COPs, with a focus on protecting and restoring ecosystems and building defences, warning systems and resilient infrastructure.

Finance will also be in the spotlight as countries continue to grapple with the fallout from COVID-19. Rich countries have yet to deliver the $100 billion per year they have pledged in climate finance, while developing states argue that this amount is but a fraction of the West’s true carbon debt. Island nations in particular have raised concerns about what will happen if and when they are no longer able to adapt to climate change, and face huge losses of lives, livelihoods, lands and cultures.

One of the most contentious issues is likely to be carbon markets, which allow countries to trade or offset their emissions for a price. Rules were supposed to be agreed at COP24 in Katowice in 2018. Instead, the issue was pushed to COP25 but negotiations broke down. This year, there is enormous pressure to forge agreement, which brings with it the risk of inadequate or damaging rules. More broadly, the so-called Paris Rulebook, which contains the detailed rules needed to make the Agreement operational, needs to be finalised.

Many leaders will probably pay lip service to the importance of fair and inclusive climate action, and a just transition to net zero. But Glasgow is unlikely to deliver much progress on a human rights-based approach to climate change, as key issues related to justice, job security, migration and conflict are not on the table. There is an opportunity to pick them up at the Stockholm+50 conference next year – the 50th anniversary of the first UN conference on the human environment, as well as through follow-up to the Secretary-General’s Our Common Agenda report (see our briefing on the report).

Perhaps wisely, COP26 has not been billed as a make-or-break moment but as a crucial milestone in our quest to avert climate catastrophe. However, with COVID-19 joining a confluence of crises and a steady drumbeat of extreme weather and dire warnings, the sense of urgency is all too real.

Photo: A wildfire at Florida Panther NWR. Photo by Josh O'Connor/USFWS.