The Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme welcomes the progress made on climate change in Durban but warns that much is left to do

If there were low expectations in the run-up to the UN Climate Convention negotiations in Durban last December, the outcomes proved far more significant than many had anticipated, including an agreement to negotiate a new, more inclusive treaty, and the establishment of a Green Climate Fund.

Indeed these outcomes, the result of marathon negotiations, reflect the growing and in some quarters unexpected determination of countries – both developed and developing – to act collectively and, in doing so, provide a clear signal and predictability to economic planners, businesses and investors about the future of low-carbon economies.

But the outcomes forged in the South African coastal city have also left the world with some serious and urgent challenges if global temperature rise is to be kept under 2° Celsius in the 21st century.

The "Bridging the Emissions Gap" report, coordinated by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) with climate modeling centres across the globe and published ahead of the Durban conference, underlined that the best available science indicates that greenhouse gas emissions need to peak before 2020.

By that time, annual global emissions need to be around 44 gigatonnes of CO2 in order to have a running chance of achieving a trajectory that halves those emissions by 2050, to below 2005 levels. The report also concluded that bridging the divide is economically and technologically doable if nations raise their emission reduction ambitions and adopt more stringent lowcarbon policies across countries and sectors. The key question arising from Durban is whether what has been decided will match the science and keep the world on track for a temperature increase of below 2° Celsius.

Crucial to what was achieved at the conference was a decision by the European Union and several other countries to continue their Kyoto Protocol commitments beyond 2012, whilst all UN member states work towards a new legally binding treaty with deeper emission reductions by 2015, to come into force sometime afterwards.

The operationalisation of the Green Climate Fund, meanwhile, is a key step forward. First proposed at the 2009 UN climate conference in Copenhagen, the fund is intended to support poor countries in adapting to, and mitigating, the effects of climate change. And reaffirmation of the commitment to mobilise $100bn for the fund by 2020 was encouraging.

In Durban, governments also agreed to establish an Adaptation Committee and a process that will lead to the establishment of a Climate Technology Centre and Network, with likely funding from the Global Environment Facility, an independent financial organisation that provides grants to developing and transitional economies for projects relating to climate change and sustainability.

But the core issue – whether over 190 nations can work together to bring emissions to the necessary level by 2020 – remains open. It is a high risk strategy for the planet and its people.

Nationally, and locally, there are some positive signs. Many governments, companies, cities and individual citizens have already begun to act. In 2010, for example, over $210bn was invested in renewable energy. But these myriad bottom-up approaches need a top to which they can aim, and the timeline for building that top is narrowing every year.

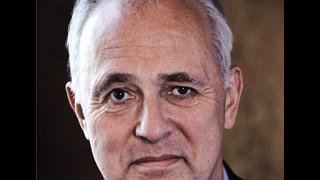

Achim Steiner is a UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme.