In order to be appreciated as universal, human rights instruments need to be developed through global discussions and negotiations involving all states.

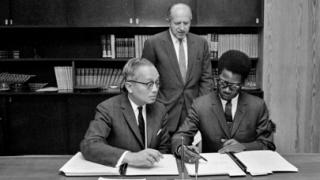

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on 10 December 1948, can be viewed as the first human rights document embodying consensus. The drafting of the UDHR involved a challenging process of forging this consensus, shaped by the moral experiences of the World Wars and the new Cold War context.

The UDHR has laid the ground for the discourse on human rights and universality, including those of critics which see the UDHR and human rights as the result of a process of western domination. Is this fair?

Inclusion or exclusion?

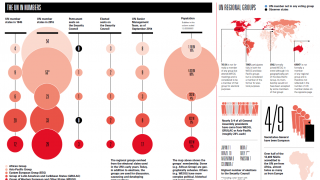

It has been argued that the drafting of the UDHR was carried out through a process that imposed strict boundaries of inclusion and exclusion in relation to political power. Even though 58 UN member states were involved in the drafting of the UDHR, the two primary actors were the 'UN Commission on Human Rights' and members of the 'UNESCO Committee on the theoretical bases of human rights'. They could be seen as creating almost a 'cosmopolitan’ space where human rights were being discussed in ways which might appear detached to the local contexts of people who would most benefit from such rights.

This group debated and negotiated the UDHR in more than a hundred sessions, and the outcome was the exclusion of particular values due to the need to find common agreement between the different particular cultural, religious and political agendas of the countries involved in the drafting. An example is the lack of reference to minorities and the rights of peoples in the UDHR.

A westernised language

The UDHR has been subject to criticisms due to its supposed ethnocentrism and rhetoric, reflecting strong western influences.

The first article of the Declaration states that ‘all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood’ Concepts such as ‘consciousness’, ‘dignity’, ‘reason’ have been often interpreted by European scholars as deriving from western philosophy. One could even consider the term ‘brotherhood’ as one which relates back to the concept of egalité of the French revolution.

However, it would be misleading to portray the UDHR only as western imposition, given the long negotiations involved the discussion of ideological and cultural differences. Further, any absences in the Declaration could be interpreted as a result of the strong desire to ensure a successful outcome to negotiations; the atrocities of World War II providing motivation and context for compromise to ensure agreement could be reached. In order to understand this critique further, it is essential to consider the compromises the countries reached and the nature of their disagreements.

Striking a balance: the dichotomy between universal and particular values

When discussing universality we need to consider ‘cultural heterogeneity’ or differences in cultural identity. This is linked to the idea of cultural relativism.

Some proponents of cultural relativism, argue that it is impossible to make a universal claim about cultures. Cultural relativists say different countries with different cultures should be able to determine their own measures of human rights implementation and one should not impose one unique model of rights.

A critique of the UDHR is the tension between different particular cultural, religious and political values and the idea that these can all be represented by a unique universal declaration. This can lead to moral paralysis though. For example, should you accept discrimination against women because it is part of a tradition within a particular culture? So how does one strike a sensible balance between cultural difference and absolute values, and how does the UDHR do so?

Contextualising universality: a way forward

Let us revisit the process of the drafting of the UDHR. Nine different representatives of diverse states and cultural background were involved in the drafting. When the draft was submitted through the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) to the General Assembly, it took a total of 81 meetings to consider the draft. 168 draft resolutions were considered, each one of them containing amendments to the various articles. This shows the amount of time and energy spent on negotiating and debating opposing and contradictory cultural, political, religious and ideological values.

Being the results of so much negotiation between various cultural values, the UDHR can represent a form of developing ‘the universal through the particular’. Indeed, Anthony Langlois called universal rights a ‘common discourse through which cultural narratives are negotiated’.

Localising rights

The logical continuation of this argument is that the universality of human rights does not require that they be implemented in the same manner in every context. Universal human rights values can be contextualised in the different regional, national and local practices in order to be effective.

The idea that human rights should be implemented in a context specific way resolves some of the tension between universal and particular values. Human rights in practice always involve striking a balance and belief in, and support for, universal human rights does not necessarily require or presuppose the universal implementation of these rights. Indeed, human rights instruments should always be contextualised, and the different cultural, social, political and economic context taken into account.

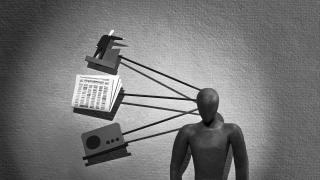

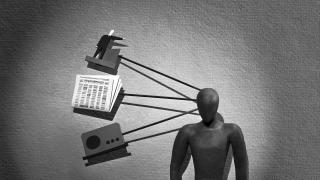

Photo: In 1948 UNESCO prepared a short avant-garde film strip to illustrate The Universal Declaration of Human Rights to all audiences. This still (frame 51) was intended to illustrate the freedom to seek and receive information and ideas. Credit: UN Photo