This review first appeared on the website of ACUNS, the Academic Council of the UN System and is reprinted by request.

The fate of the United Nations concerns all those with a stake in the effectiveness and legitimacy of the international system that has been built since 1945. The concurrent emergence of new global challenges and the ongoing realignment in global wealth and power provide the context in which we must rethink our assumptions and engage our collective creativity. Do new actors and new threats mean that the utility of the UN, founded 73 years ago with the fundamental aim of preventing a repeat of the twentieth century’s two world wars, has run its course? The contributors to this volume are outstanding scholars, analysts and practitioners from around the world, who in the words of the editors, Thomas G. Weiss and Sam Daws, are also “critical multilateralists…who see the need for international cooperation to solve many challenges to human survival with dignity.”

The UN has a crucial role to play in promoting a peaceful and just international order – a role that is multifaceted. It is the UN, through the Security Council, that has the primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security, and in so doing, preventing the eruption of deadly conflict which undermines both order and justice. Sebastian Von Einsiedel and David M. Malone highlight the dynamics that have often resulted in the Council’s inconsistent decisions, selective interventions, and paralysis. If representativeness is a key characteristic of legitimacy in the twenty-first century, what can be said about the Security Council which represents the political realities of 1945, not of 2018? They warn, “while the hurdles for achieving reform are high, over time the failure to do so is likely to erode the engagement of key member states in the UN’s work.” (p.160)

In discussing the practices of the United Nations it is sensible to refer to the UN Charter. However, in the case of peacekeeping such a recourse will leave us confounded for there is, famously, no mention of peacekeeping at all in the Charter. The history of UN peace operations as Richard Gowan explains is “a cyclical story involving periods of intensive experimentation and growth punctuated by phases of retraction and caution.” (p.421) It is also the case that the UN typically takes on the hardest cases. It is the actor of last resort where neighboring countries or external powers find few tools at their disposal. And despite the failings of the UN’s peace operations the Organization “has a long track record of experimenting with mission models, learning from failure, and looking for different ways to handle ensuing crises.” (p.440)

During the past seven decades, the UN has provided normative leadership, advancing aims such as human rights, gender equality and sustainable development through the work of its agencies, funds and programs, the policies agreed by its members, and the public pronouncements of its leaders. One of the most interesting chapters in this volume is “Humanitarian Intervention and the Responsibility to Protect” by Ramesh Thakur who served on the Canadian-sponsored International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) which developed the innovative concept of R2P in 2001 to replace the popular term “humanitarian intervention.” At the 2005 World Summit, all UN member states unanimously accepted their Responsibility to Protect their own populations from four mass atrocity crimes: genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. They also expressed their readiness to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner, through the Security Council, when peaceful means are inadequate and national authorities fail to protect their own populations. Thakur argues that, “In the post-R2P era, the two paradigmatic cases to date that highlight its mobilizing power but also underline its problems might well comprise Libya in 2011 when NATO led a UN-authorized R2P intervention, and Syria since 2011 where despite large numbers of civilian deaths and the confirmed use of chemical weapons, the United Nations failed to take robust and effective action.” (pp.472-473) He provides a sobering forecast regarding action to prevent and halt conscience-shocking atrocities: “the response of states – whether individually, in groups, or collectively through the United Nations – is likely to continue being ad hoc and occurring on a case-by-case basis, rather than principled and consistent.” (p.476)

Richard J. Goldstone’s chapter “International Criminal Court and Ad Hoc Tribunals” takes stock of the achievements in international criminal justice over the past 25 years, as well as the challenges currently facing the ICC. In a short amount of time, the work of the ICC, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and ‘hybrid’ or ‘mixed’ courts has done much to make international criminal accountability a reality. And yet, it remains true that efforts to consolidate and further international criminal justice confront significant obstacles. Notably, state cooperation is critical to the success of the ICC, which lacks its own enforcement organ, and the work of the Court has been dogged by a lack of such cooperation.

Although the UN is an intergovernmental organization led by its member states, when we talk of leadership, we tend to think of the Secretary-General. And an effective Secretary-General can make the difference between change and stasis. Edward Newman notes that admirable steps were taken to make the appointment process of the current Secretary-General more rational and less opaque: “The manner in which Antonio Gutteres was appointed in 2016 reflected a genuine change in the appointment process, with an unprecedented level of transparency and a real focus on the qualifications of candidates and their vision.” (pp.232-233)

Rarely is an edited volume so coherent and authoritative as this one. Weiss and Daws have accomplished their purpose “to bring alive the historical, legal, political, and administrative details of the UN’s many roles.” (p.ix) This Handbook will contribute to a better understanding of the United Nations, and serve the collective mission of those committed to ensuring that the peoples of the world are able to live, as is their birthright, in the ‘larger freedom’ which the UN Charter promises to all.

UNA-UK's Executive Director wrote a chapter for the Oxford Handbook. See the back page of the magazine to purchase the handbook at a discount.

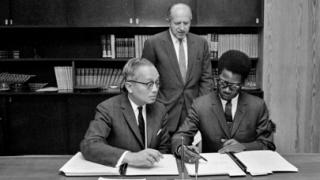

Photo: a detail from the frontcover of the Oxford Handbook.