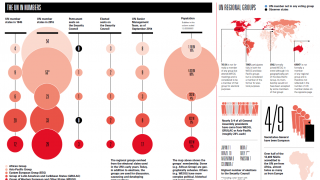

The ICC was designed as a court of last resort to have jurisdiction over persons accused of some of the most abhorrent international crimes - genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. The court is currently investigating 11 situations: 10 of which are in Africa. These numbers have sparked backlash against the court, with accusations that it only investigates and prosecutes Africans. So, is the court biased or are we asking the wrong questions?

The ICC is also overseeing 9 preliminary examinations –precursors to potential investigations. And the majority underway are not in Africa. Indeed in its two decades of operation the court has mounted investigations in 25 countries, 12 have been African.

The idea that the court turns a blind eye to perpetrators in other regions has gained traction across the African continent. Some political leaders have threatened to withdraw from the court: Burundi - the first and so far only to officially start the process of withdrawing - accused the court of being “a political instrument and weapon used by the west to enslave other states”. Others including South Africa and Gambia have expressed intent to quit as members of the court: Gambia declared its move to withdraw and then rejoined, while South Africa’s position is unclear and is currently in the hands of a court case in SA.

The court can receive referrals from the UN Security Council (as seen in Libya and Sudan) but it mainly operates on the principle of consent. Indeed, the majority of African countries under current investigation (DRC, Uganda, Mali, CAR I, and CAR II) have arisen from self-referrals. In the case of Cote d’Ivoire, it accepted the Court’s ad hoc jurisdiction. Only in two of the African cases now open - Kenya and Burundi - has the ICC actually exercised its right to start investigations. The “African bias” of the ICC is therefore in many cases a symptom of African enthusiasm for the ICC. Indeed, African support was central to the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

There are valid criticisms of ICC action: It relies on the cooperation of member states, including those the court may one day have to prosecute. It is also closely tied to the United Nations Security Council: Russia, China and the United States, three of the Permanent Five veto-wielding members of the UN SC have still refused to join the ICC and yet they can decide if the court can investigate atrocities committed by non-court signatories. This poses a legitimacy problem for an ostensibly global court and raises questions over its credibility.

If the ICC’s ever going to rid the criticism it receives, it will require that the international community grapple with these political realities, rather than simply demanding that the prosecutor look elsewhere. So, rather than demanding that the ICC not pursue justice, primarily requested by Africans, in Africa, critics should be demanding that investigations elsewhere not be blocked.

The useful question to ask here would be: Why hasn’t the ICC been able to exercise jurisdiction over atrocity situations outside of Africa? Two reasons come to light: many of these states have not joined the ICC and therefore do not recognise the court’s jurisdiction (34 of 54 African UN member states are parties to the court. 89 of the 139 other UN member states are. While these proportions are similar, the 50 non-African states that have not joined the court include almost all the world’s non-African fragile and conflict affected states). And states that have not joined are protected by veto-wielding powers at the UN Security Council.

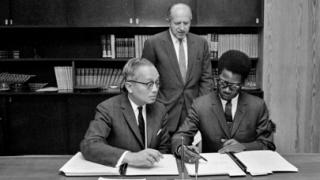

It is also important to remember that the ICC is a court of last resort and that justice can and has been achieved through other pre-existing mechanisms. While political expediency remains l’ordre du jour, we have seen forward strides in international justice. And ad hoc predecessors in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia (which were established under the UN Security Council’s authority) have helped pave the way. The ICTY alone has seen ninety individuals sentenced for genocide, crimes against humanity or other crimes.

Therefore, focusing on whether the ICC is biased against Africa reflects the court’s jurisdictional limits but distracts from more fundamental questions around the ICC and international justice more broadly ,and doesn’t resolve the deeper political questions concerning sovereignty and power.

The ICC was constructed with the idealistic goal to end the presumption of impunity for the powerful. Yet many stronger states that use violence against civilians have protected themselves from the court’s jurisdiction. Weaker states, vulnerable to violence, have opened themselves up to the court’s jurisdiction. So rather than a weapon of the weak against the powerful, the court has mostly been used as a weapon of the weak (fragile states) against the weaker (non-state actors). Thus, of the 6 persons in custody (as of September 2018) 2 are state actors and 4 are non-state actors. Laurent Gbagbo is the first-ever head of state to be handed over to the ICC.

Meanwhile, impunity still reigns despite equally shocking violations of international law occurring in countries like Myanmar and Cameroon, Yemen and Syria. Attacking the ICC takes the attention away from where it should be focused: on states themselves.

Let’s not forget the ICC has come a long way. It has gained increasing acceptance that has strengthened its guardianship of criminal justice. With international support and backing, the ICC can continue to set a precedent; that atrocity crimes are unacceptable and justice will be dealt.

Photo: Laurel Hart/Ntarama Genocide Memorial, Rwanda.