Current UK policy on developing countries highlights UK trade, believing that this delivers mutual prosperity and encourages economic development while promoting UK commercial interests. The question is: does it?

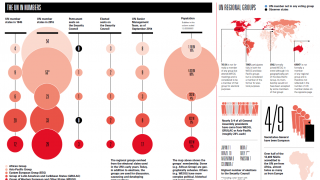

The UK Government recognises that developing countries are a key partner in trade. In 2016, the UK’s total trade with developing countries was £51.7 billion – more than twice our total trade with Japan and more that our total trade with Italy or Spain. The UK’s trading relationships with developing countries positively impact UK consumers by providing a wider choice of everyday goods at lower cost, making household incomes go further. For UK businesses, imports from developing countries support UK exports. For example, according to UN comtrade data, in 2016, 48% of UK imports of un-processed tea came from Kenya, 10% of imports of prepared fish came from Ghana, and 21% of T-shirts came from Bangladesh.

The benefits for the UK are clear and the UK is investing to ensure that they continue. In her recent visit to Africa, Prime Minister Theresa May announced that the UK will be carrying over the European Union’s Economic Partnership Agreement with the Southern African Customs Union and Mozambique after the UK leaves the EU, rolled out a £4 billion programme of UK investment for African economies and declared UK’s ambition to be G7’s number one investor in Africa via an African Investment Summit in London next year to help UK investors and African governments forge closer ties with one another.

UK government departmental strategies are also becoming more ambitious in relation to trading with developing countries. The Department for International Development’s Economic Development Strategy puts a strong emphasis on opening and growing markets, focusing on trade as an engine for poverty reduction. Last year, the Department for International Trade published its Trade White Paper “Preparing for our future UK trade policy” outlining their commitment to maintain market access for developing countries and support to developing countries to break down the barriers to trade, with the hoped-for effects of increasing incomes and reducing poverty. DIT’s new Export Strategy aims to ensure that government has the right financial, practical and promotional support in place to allow British businesses benefit from growth opportunities in developing countries. In addition, the strategy explores how exporting contributes to the government’s agenda for prosperity, stability and security.

But is this as beneficial to developing countries as it is to the UK? Certainly, economic globalisation has benefits, but is also powerfully marginalising. For example, Nigeria’s economy is thriving, yet 87 million Nigerians still live on less than $1.90 a day. Increased prosperity is only synonymous with development if the resultant wealth is shared equitably and invested sustainably.

Demographic challenges increase the urgency of this agenda. Rapid population growth is a fundamental problem in Africa, home to most of the world’s people living under $2 a day and where 60 per cent aged under 25. Between now and 2035, African nations will need to create 18 million new jobs every year just to keep pace with the rapidly growing population; amounting to nearly 50,000 new jobs every day. Several African leaders including Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo and Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari have identified jobs as the number one demand of their people and their greatest political priority.

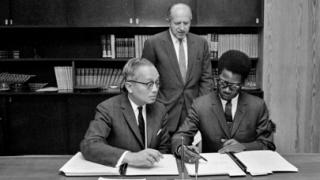

Extreme poverty also cannot be eradicated without considerable additional investment, far in excess of the amount currently provided by aid ($140 billion a year). Estimates from the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA), suggest the need is for $3.5trillion a year to meet all of the SDGs. In Mexico in 2002, over fifty heads of state and two hundred finance, foreign, and international development ministers formally agreed the Monterrey Consensus - endorsing a mixed approach to development involving both state and private sector and a combination of external government-issued aid, as well as foreign investment and trade had an essential role to play in international development.

The UK government believes that commercial and development objectives are conducive, and that a commercial-development strategy is a win-win for developing countries and will lead to sustainable, inclusive growth. The argument is that developing countries can overcome their dependence on aid by creating wealth and generating revenue for national governments. The private sector can drive this growth: creating jobs and opportunities through increased trade activity.

By helping developing countries trade more with the UK and the rest of the world, the UK can support their economic development which helps drive growth and jobs in a way that aid-spending alone cannot. This will not only accelerate poverty reduction by helping developing countries harness the power of trade and investment, but also build more prosperous economies to the mutual benefit of UK citizens and businesses. In this sense, I would argue that trade with developing countries is one of the most cost-effective poverty–reducing policies available.

Then, is the UK capable of delivering this strategy? To drive this agenda forward, the UK Government is collaborating across Whitehall on trade and development issues, both in London and overseas. Further, the UK is a global trading nation and has a comparative advantage in higher-value goods and services in pro-poor sectors such as infrastructure, financial services, agri-tech and healthcare. These sectors support developing countries in becoming moderate to high-income countries. Concurrently, the UK is also a leading development power, and one of the few countries that has consistently contributed 0.7% of its Gross Domestic Product to Official Development Assistance since 2015. The UK is seen as a champion of both trade and development. This has allowed us to develop strong and trusting relationships with the governments of developing countries.

There will undeniably be challenges – such as ensuring high quality jobs, and managing expectations by being realistic about the pace of change and that job creation will take different forms. Nevertheless, increasing trade with developing countries should be mutually beneficial for both the developing countries and the UK: delivering global prosperity and poverty alleviation. The Prime Minister has mentioned that the UK will use influence and our global standing to encourage other developed powers and global institutions to have the same approach to delivering the Sustainable Development Goals. With the global economy becoming increasingly integrated, it is time for nations to work together on global prosperity as partners instead of competitors, and realise that developing countries’ problems are also our problems.

Photo: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia where the AAAA was agreed. Credit: creative comms (Flikr user ibolyka1)