This piece appeared earlier on our website.

Kofi A. Annan, who died on 18 August at the age of 80, was the 7th Secretary-General of the United Nations, serving two terms from 1997 to 2006. In the view of many he was also the most successful holder of that office to date, with the possible exception of Dag Hammarskjöld, who died in the service of peace in the Congo in 1961.

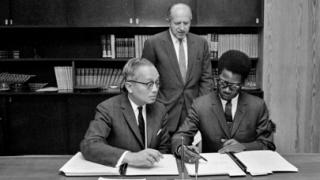

Annan was also exceptional in being the first, and so far only, Secretary-General to rise to that office through the ranks of the UN system, having started in 1962 at the lowest professional grade in the World Health Organization.

During that long career he impressed many colleagues and interlocutors with his quiet competence, and also his ability to work on friendly terms with a wide variety of people. Normally that would not be enough to secure appointment as Secretary-General – a decision in the hands of the Security Council, and usually favouring a prominent politician or diplomat with experience mainly serving his own country. But the circumstances in 1996 were unusual.

The Clinton administration in the United States had decided, largely for reasons of domestic politics, not to allow the incumbent Secretary-General, the Egyptian Boutros Boutros-Ghali, to serve a second term. Boutros-Ghali was the first African to hold the office, and the US knew he could only be replaced, politically, by someone from the same continent. Annan, from Ghana, was the senior African in the Secretariat at the time, and had impressed the Americans with his cooperative and pragmatic approach as Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, particularly in the former Yugoslavia.

Many expected, therefore, that he would be a low-key, inconspicuous leader – “more secretary than general”. This proved wrong. Annan saw, like his predecessor, that the post-cold-war-world offered great opportunities to the UN, but also saw that these could be exploited only if approached with tact, caution, and a degree of humility.

Annan saw, like his predecessor, that the post-cold-war-world offered great opportunities to the UN, but also saw that these could be exploited only if approached with tact, caution, and a degree of humility.

With hindsight, one can say that he was fortunate in the time that he came to office. The 1990s were a period of relative harmony among the great powers. With Russia still licking its wounds after the collapse of the Soviet Union and China devoted to a policy of “peaceful rise”, there was no serious challenge to American hegemony, and the five permanent members of the Security Council were able to reach consensus on a wider range of issues than either before or since. This gave an adroit Secretary-General greater freedom of manoeuvre, and enabled him to provide a stronger form of leadership.

At the same time, the twin phenomena that produced globalisation – greater economic openness and the arrival of new, ultra-rapid means of communication – meant that states were no longer the only important actors in the international system, and that a good communicator could reach a global audience far beyond the ranks of governments and diplomats.