In the face of rising mobility, urbanisation, the increasing need for foreign workers, and the rapid evolution of instant, global communications, one often wonders whether we are making any progress at all in forging peace and friendship across our different identities.

Increasingly, I am surrounded by friends and colleagues whose multiple, multilayered, contextual, dynamic identities are a given. My Hungarian-Senegalese children in Dakar speak four languages with ease and can recite both Catholic and Muslim prayers. However, while intercultural marriages prove that differences can be overcome by love and respect, general public discourse is often rather discouraging.

Fear of the unknown is on the rise. The conflation of race, religion, nationality or status is a common tool in populist propaganda when politicians want to appear as saviours of a falsely claimed homogenous national identity and culture, which has never really existed anywhere in modern history. They know too well that as long as people are busy analysing their differences and are kept separate along ethnic, national, religious or linguistic lines, they will not be able to unite to demand civil, public, political or socio-economic rights and changes, such as equal access to quality education, proper health care or

ending corruption, to mention just a few.

But our challenge in safeguarding pluralism lies not only in countries where political will is lacking because of a manipulative agenda. There are many others that seemingly accept or even cherish diversity, yet fail to put in place even the minimum necessary guarantees to manage it.

Of course, managing diversity is a complex task. It requires political leadership that assesses challenges courageously and regularly, and designs specific legislation, policies and programmes with corresponding budgets to tackle and, eventually, overcome them.

Sadly, at the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, we often come across governments that do not understand our suggestions in this regard. Some even reject them outright.

During our last session this summer, we listened to a head of delegation who maintained that collecting disaggregated data would endanger racial harmony in his country. We heard arguments that communities suffering caste-based discrimination should not fall within our remit. We learned about the establishment of specialised bodies for minorities that had no representatives of those minorities. We were told that asylum-seekers from one particular country are obviously all economic migrants and therefore can be lawfully returned to their home country in the absence of an appropriate legal and formal procedure. It was a disturbing, but sadly not untypical, session.

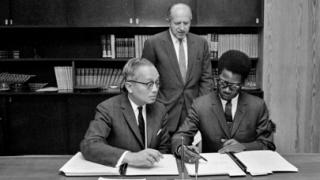

Perhaps what disturbs me most, though, is the obvious lack of open and systematic communication channels between decision-makers and vulnerable groups, such as minorities or indigenous peoples, even in the most progressive countries. I often wonder how we can improve our efforts to prevent human rights violations if governments do not build relationships and trust with those at risk of violence and atrocities – precisely the people who should be flagging early warning signs or reporting crimes. It is alarming that more than 50 years after the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination was adopted, we still have glaring gaps in some of the most fundamental prerequisites for securing racial, ethnic, religious and linguistic harmony.

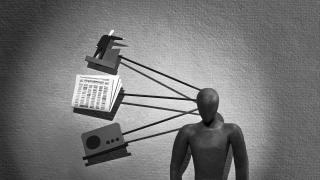

We must also be alert to the dangers that social media bring. Various studies show that algorithms are built to maximise user engagement and the posts that perform best tap into negative, primal emotions like anger or fear. I have noticed a very disturbing phenomenon on my own social media feeds. Hatemongers seem much more organised, strategic and active – and much louder – than peace lovers, which enables them to dominate the discourse and gives a false impression that they outnumber other voices.

Having met with hundreds (if not thousands) of people in the more than 50 countries I have visited in recent years, I firmly believe that we, the peace lovers, are indeed the critical mass. But we must change our ways of communication. We must learn to be more expressive and outspoken. We must become active antiracist advocates because, as Holocaust survivor and activist Elie Wiesel, said: “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference.”

This is especially the case at a time of growing scepticism towards multilateralism, and the doubts expressed in various parts of the world as to whether we can all be bound by the same set of universal values. My answer is rooted in our shared history.

There is a multitude of regional and international treaties and agreements that cover a vast range of issues. They were not created in a vacuum but result from the recognition, after terrible human tragedies, that we must better co-operate to secure peace, security, development and human rights. Let us honour this commitment by carefully studying and reinforcing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which will be 70 years old this December and starts by declaring that: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

Photo: The Catholic Cathedral in Dakar, Senegal. Roughly 7% of the population of Senegal is Christian and 92% Muslim. Credit: "Manu25" via creative comms