Let me begin with an appeal to our venerable friend, the United Nations: get down on the ground with the grandchildren! For as long as I have known it, the UN has often seemed prematurely old. Today, as it marks its 75th anniversary, a youth challenge is being mounted to the ways in which we live, organise and govern ourselves. This challenge is much larger than the UN. A digital revolution on the one hand, and rising social and economic inequality on the other, will unseat a ruling establishment that has failed to navigate these ideas. The UN must be part of that future or it will be pushed aside.

While the Organization has proved it can be flexible and innovative – think peace operations, private sector partnerships and blockchain in the field – it has struggled from the outset with its Anglo-Saxon DNA, as the world began its march to more globally distributed power.

The UN Charter’s vision of a world order managed by the Allied victors of the Second World War was out of date before the ink was dry. The Organization’s vision and mission had universal appeal, but were framed in Western language and approaches, even as its membership swelled from 51 states in 1945 to 193 today. One of the UN’s proudest achievements is undoubtedly its role in supporting this transition – from a world where almost a third of the global population lived in non-self governing territories, to today’s multipolar international community.

There was early opposition to Western dominance in the General Assembly, where new Member States sought to correct the historical and structural imbalances in the global political economy. The Non-Aligned Movement and Group of 77 championed a ‘new international economic order’. At the time, it seemed likely to remain a permanent backbench cause.

Now, however, it is not a simple division of East and West or North and South. Many of us have added collective social and economic rights to our own agendas. Issues such as climate justice, structural inequalities and the injustices of the global economic system are just as likely to come from a British human rights NGO as they are from a Rwandan farming cooperative.

At the same time, a more authoritarian model of government is gaining traction across the world. It embraces leaders who come to power by the ballot box as well as those who did not, but all share a preference for a nationalist foreign policy, weakening of domestic institutions and the rule of law including the political rights of its citizens, and a casual disregard for minority and, in some cases, majority rights.

Between them, Brazil, China, Hungary, India, Russia, Turkey and the United States (under Donald Trump until 21 January) represent a demographic majority. And many others are borrowing from their playbook. Freedom House notes that last year was the 14th consecutive year of decline in global freedom, with 64 countries experiencing an erosion of political rights.

The appeal of their arguments is unlikely to dissolve any time soon. The uneven impact of economic change, now accelerated by COVID-19, has produced political divisions across the world: urban versus rural; young versus old; university-educated versus high school or less; those employed in new services sectors versus those in failing industrial sectors. Economic security, cultural identity and a strong anti-immigration stance are the flagship issues of a new populist politics that reaches those who feel they are being left behind by unsettling change.

As a consequence this is, perhaps inevitably, an age of UN caution. In a way, it was ever thus.

I remember in my first UN year, 1976, an older generation – including the self-named ‘last of the Mohicans’ founded by those who has joined the UN Secretariat before 15 August 1946 (see Robert Kaminker’s piece on page 20 and online) – complaining in not dissimilar terms. The place already seemed stiff, cautiously bureaucratic and a bit rundown.

Then, as now, the UN sought to make up for the Cold War’s political black hole by swarming the humanitarian and development space with compensating activity. From the 1960s to the 1980s, its direct operational capacities – to address refugee flows and hunger, to boost literacy and vaccinations – grew rapidly. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) went from a small staff of lawyers to a large staff of logisticians. This year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner, the World Food Programme, was spun out of the Food & Agriculture Organization. The technical assistance of specialised agencies provided critical support to newly independent governments.

In 1980, UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim visited a UNHCR-supported refugee camp on the Thai–Cambodian border where I was the field officer in charge. He turned to me in bewilderment, as we toured the encampment with its heavy UN and NGO presence and asked how this huge operation could have been set up without him knowing almost anything about it.

I tell this story to illustrate a simple truth. The political and security UN in New York may have been gridlocked but there was ample space for activism and innovation as long as you stayed well away from that graveyard, the Security Council. Operations like mine were run in the field and from Geneva, based on a mandate derived from international law, not the Council’s permission.

As I crisscrossed the world for UNHCR from refugee hotspots in South East Asia, Pakistan and Afghanistan, Central America and the Horn of Africa, I saw their impact first-hand: countless lives saved and re-started. The politics were never easy, the compromises often disappointing, and the motives of major inter ested powers and donors only rarely altruistic, but the space was carved out and generally held.

Today, the UN has also found space – notably around the Sustainable Development Goals (the SDGs) which play to the UN’s convening and standard-setting roles; climate change which three Secretaries-General have made a priority; and a tragically expanded humanitarian function as grim conflicts in Yemen, Syria and elsewhere stubbornly run on.

A UN seeking to focus on issues where it won’t be bullied by its stronger members, or ignored by others, is not new. In fact, it has been condemned to this condition for most of its 75 years. Its glorious conception period ended after a few months, around the time of Churchill’s ‘iron curtain’ speech in March 1946.

Kofi Annan’s Secretary-Generalship was a second honeymoon: coming six years after the fall of the Berlin Wall it was a moment of hope and alignment between the major powers of which he took ample advantage to advance political, security and human rights matters. Yet in the aftermath of a Security Council broken on the anvil of the US–UK invasion of Iraq a gale turned on him, too. So it is only for 10% – at most – of the UN’s 75 years that the wind has blown strongly in the right direction.

Bending the sale

Annan was fond of quoting the African proverb, “you cannot bend the wind so bend the sail.”

I want to suggest a manifesto for a re-purposed UN that is both true to its Charter; but recognises the direction the winds are blowing; that does not cling to the mast of a failing Western liberalism alone, but understands and responds to the dynamics that have left that liberalism, and it seems multilateralism, on the rocks.

This is a comeback strategy for the world as it is; in order to allow us to make the world as we want it to be. And the vehicle for this cannot be our grandparents’ UN.

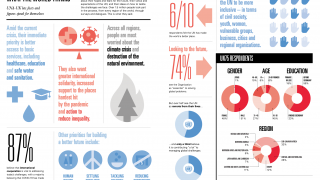

The world needs to believe the UN matters. While the Organization still enjoys high levels of support, as the UN75 global consultation (see page 6 of the magazine) shows, this seems to be grounded in what people think it should do, rather than what it actually does. Support falls when pollsters ask about the UN’s performance in specific areas.

Without a more passionate public embrace it will be hard to overcome the inter-state fault lines.

Annan was possibly unique among Secretaries-General in being able to appeal directly to people, citing the opening words of the Charter in justification: “We, the Peoples of the United Nations.” Those before and since have been largely captives of governments and their disagreements.

I often wish the UN’s supporters would accept a more pragmatic UN rather than the aspirational “save the world” version that lights up the top line poll findings. It will always disappoint such hopes. The UN is of the world, not above it.

The UN75 global consultation found that across very different national economies and circumstances there is a demand for better delivery of basic services; for action to address climate change and protect the environment; and for honest accountable government that delivers and protects its citizens. This is already the UN’s agenda.

The UN is not going to replace governments as an agent of service delivery. It does not command the resources or the authority. But the UN must deploy its convening, campaigning and normative roles to double down on its SDG agenda. COVID-19 has attacked that agenda, as Bill and Melinda Gates have said, setting back 25 years of progress in 25 weeks; driving 115 million people back into extreme poverty this year and raising fears for economic security in almost every family. The UN has a unique platform to measure a country’s progress, league table it, and name and shame those whose social and economic indicators fall behind.

The current Secretary-General António Guterres dedicated most of his early period in office to conflict resolution – including in Syria, Libya, Yemen, Somalia and Cyprus. His efforts were not blessed with any major breakthroughs. He then embraced the SDGs and climate action, a pivot illustrated by a Time magazine cover featuring him wearing a suit, standing in rising sea water. This July, he delivered the Mandela lecture and called for “a new social contract for a new era”, eloquently setting out the longstanding risks laid bare by the pandemic, such as inequality. It was probably his most noticed speech to date.

Secretaries-General were elected to be the world’s chief diplomat; today, successful ones quickly learn they have to be the world’s chief campaigner. And like any campaigning organisation, the UN must begin by understanding its base constituency: “We, the Peoples”.

The Bennett Institute at Cambridge University has recently released a study of the state of global democracy that draws on more than 3,500 country surveys. It finds support for democracy is at a low ebb: a clear majority are dissatisfied with democracy, with 18–34 year olds the most disenchanted in almost all regions of the world.

But the report stressed that, much like it is for the UN, this is not a rejection of the theory of democracy but disappointment with its results. Indeed, where governments do deliver results, notably in some Asian countries, dissatisfaction is much lower.

This is a protest against poorly performing incumbents. People don’t feel protected. In rich countries, they don’t see a better future; they see wave after wave of threatening change driven not only by pandemics but by technology, trade, environmental degradation and deepening inequality. In developing countries there is more optimism about the future, but also growing frustration at structural insecurity – and the knowledge that aspiring to return to “normal” will not improve their lives.

The protests of a generation cannot be brushed under the COVID carpet much longer. The world was not a happy place before the pandemic, with soaring youth unemployment, exclusion and skewed inter-generational distribution of wealth and government benefits. And we know there is worse to come.

Here is the UN’s great cause. It should throw caution to the winds and lay out Guterres’ new social contract for the world to see. It should mobilise younger citizens and convene governments to build a new global bargain. It should put governments on the spot by indexing and spotlighting performance to expose which are delivering and which aren’t.

And on the coattails of this campaign, it should remake the argument for multilateralism. Once the UN is reconnected to grassroots concerns, it is not a hard argument to make – that problems such as climate change require global cooperation and action.

To have legs, such a campaign must find allies where it can – including, and especially, outside the UN system – and it must not be constrained by the foot-dragging back end of the General Assembly.

When the UN has touched the stars, the lift has come from civil society not government, from San Francisco to human rights advances, environmental action and the SDGs.

Today around each SDG clusters a network of champions. In many, corporates show greater ambition than governments; in all, the most innovative thinking comes from the many corners of the civil society mosaic: local and international NGOs, mayors and their cities, activists and academics.

Building a variegated coalition of states and non-state actors willing to be first movers on different parts of this agenda is a not a new path to action in the UN. Now it needs to be turbo-charged. The world won’t wait for the most plodding and resistant nations to sign up to action.

This same approach needs to be applied across the board: the High Commissioner for Human Rights should be able to marshal states and NGOs that champion rights and raise their voices when she cannot. UN country teams must be critical protectors and promoters of local civil society voices.

Too many governments see the current political climate as a license to step on their home critics. The UN needs to step in and protect its partners on the ground. A global social contract would be stillborn without them.

And the final step to restored effectiveness must be recovering authority in the political and security space. If there is a silver lining here, it is that the character of conflict continues to change opening grim new opportunity. Not only is peacekeeping less than ever the ‘thin blue line’ between states, it is not even, in many cases policing full-blown internal conflicts in countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo or Syria, as it has done in the past.

The more likely future of conflict, at least where the UN will have a role, is low level but persistent political violence around exclusion, suppression of minority rights and inter-generational conflict in a context of deteriorating state institutions such as policing, justice and social service delivery. The World Bank has estimated that by 2030 two thirds of the world’s extreme poor could be living in areas of conflict and violence. The way into these situations will be via humanitarian, development and human rights work. The UN will not have to wait for the permission of the Security Council: it is there already.

This not a manifesto to change the world overnight. Rather it is a call for the UN to seize the moment and take advantage of the opportunities it has at this moment of global crisis to recover relevance and to drive a new global consensus on tackling our collective weaknesses that COVID-19 has so cruelly exposed.

There is a majority out there for a better governed and prepared, more caring and inclusive world but that same majority has grown terminally impatient with existing institutions. The UN can be part of that failed past or attach itself to an emerging future.

Let the campaign begin.

This article is adapted from the UN University WIDER Annual Lecture – find the full recording at www.wider.unu.edu.

Photo: A UN World Food Programme helicopter discharges supplies in South Sudan. WFP won the Nobel Prize this year in recognition of their work as the backbone of UN logistics © UNICEF/Peter Martell