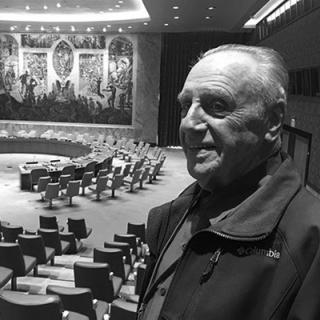

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the UN, we spoke to someone who has been with the organisation since its very first day.

Robert Kaminker joined the United Nations as an 18 year old proofreader, and spent the next 37 years in administrative roles for the Organisation across five continents. Two years ago he recorded a wonderful interview with UN Radio. So, for the UN’s 75th anniversary we decided to check back in with him and ask for some more of his reflections…

Describe the atmosphere in those early days:

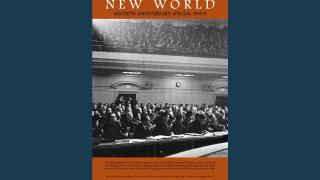

On 10 January 1946, I reported to the UNO personnel office in Church House in London to take up the position of reader in the French language typing pool of the UN Secretariat. I was 18 and 9 months old and I had been recruited in France out of school.

In those first 4 months in I met many people who had had the same set of feelings and hopes that I had. Most of them had just survived 6 or 7 years of war, some in occupied territory, others as soldiers, or prisoners of war, or in resistance commandoes, a few as survivors of concentration camps. All had suffered from lack of food, clothes, freedom to move or communicate. But all had now two characteristics in common: an intense desire to see the world achieve peace, and a strong hope that the aims expressed in the UN Charter would be fulfilled.

What does the charter mean to you? How can it be achieved?

The Charter defines how the peoples of the world should ideally live together. It takes into account the numerous problems and offers ways of solving them, or at least avenues leading to solutions. The first few years of the United Nations were occupied with the move to the United States and the setting up of the Headquarters, though the Security Council was already occupied with conflicts such as the border dispute between Greece and Albania. But the process of diplomacy did not hold us back from achieving substantive progress, such as the creation in 1946 of UNICEF to care for the children of Eastern Europe.

Little by little, as it slowly came to understand the diversity of the world, the UN began implementing the Charter by creating Specialized Agencies such as the WHO, FAO, and establishing organs such as UNDP dedicated to solving or at least alleviating specific problems.

This meant that successive General Assemblies had growing agendas and adopted an increasing number of resolutions. As staff members, we witnessed the growth both of the agenda and of the organisation with many staff recruited.

This atmosphere began to change with the advent of the success of the work of the Trusteeship Council in the decolonisation of dozens of countries. To ensure these newcomers were represented in the Secretariat, many were recruited. They had a different attitude: they had, with few exceptions, not been subject to World War 2, but were liberated from colonialism. Their motivation toward the UN was as strong as that of their predecessors, but was of a different kind: as most of their homelands were underdeveloped, they aspired to change for the better.

In what other ways have you seen the organisation change?

An important dynamic I have not yet mentioned is that created by the “cold war”. As many of my colleagues, I deplored the impasse the cold war created, which I felt was due to the “do as I say, but don’t do as I do” attitude of certain countries. We were however convinced that things would not be like this forever, and indeed as the Soviet Union evolved things changed for the better.

Secretaries-General came and went in the UN. The one most popular with the staff was Dag Hammerskjold, he really was the chief! We felt that he was one of us, as most of the other SG’s appeared too busy politically to keep abreast of staff problems.

With each newly appointed Secretary General, certain changes occurred. Just a few examples I observed:

- Boutros Boutros Ghali was very strong on publicizing his name, the UN Public Information Department had instructions to that effect.

- Kurt Waldheim seemed intent on solving the Cyprus situation and certain Greek and Turkish new staff were recruited.

- Perez de Cuellar led a campaign to stop nepotism in the Secretariat.

Others such as U Thant or Ban Ki Moon were at the head of the Organisation at times when little progress was possible. All Secretaries-General have had the headache of timidity or unwillingness to support the UN on the part of the leaders of influential states such as the USA, Russia, France, UK, Germany, and India.

Tell us about your own career, what are you most proud of?

During the 36 years of my career with the UN, I spent some 20 years at UN HQ in various administrative posts, while climbing the hierarchy of the Secretariat in Conference Services, Languages Division, and reaching the position of Administrative Executive Officer in the Department of Public Information. I was also posted in the former Belgian Congo in 1961 for 18 months. Then in Santiago Chile, Bangkok, Beirut, New York again, and Geneva at the end.

These assignments, which usually lasted for 2-4 years, as well as shorter missions such as the creation of the IAEA, the Conference on the Law of the Sea, or the Conference on Zimbawe and Namibia, were sometimes difficult, but because of their narrow purpose, were extremely fulfilling. One saw the result of one’s work immediately without it being diluted in the vastness of the HQ bureaucracy.

In New York, we read the New York Times which reported the activities of the UN quite fully and mostly in a fair way. And each time an article gave the organisation praise, we all felt proud. Each one of us staff members at all levels was happy whenever something they had done or written was reported as being a positive step moving towards something. Naturally, the various stages of the cold war were deplored by the staff, as was news of poverty, famine, armed conflicts and other events which demonstrated that we had yet to achieve the promise of the UN Charter.

Personally, as Administrative Officer in overall charge of the management of the UN Conference on the Law of the Sea held in Caracas Venezuela in 1974, I felt happy that it had been successful. It was a significant step in the development of maritime law and we were able to administer it within budget.

What do you think it means to be an international civil servant? Was the term differently understood by staff with different backgrounds?

As members of the Secretariat under oath, I would say that we were charged with the duty of doing our very best to implement the tasks given to us by our superiors who, in turn, were tasked through the resolutions adopted by the various governing bodies of member states.

At certain levels, this involved working in teams, and sometimes having to seek mediation between different ways of understanding the work. But I must say that the different backgrounds and nationalities of staff did not cause problems: we were able to negotiate a shared understanding of what was required, and staff members who came from antagonistic countries participated in these conversations without any restraint.

At times an Eastern European colleague would ask for postponement of a decision to give him time to “consult” the ambassador from his country! I have always considered such a practise to be contrary to our oath. We were international civil servants, and our own nationalities served to give the UN staff community its multinational intercultural character.

What message would you like to leave us with?

The United Nations is 75 years old! And yet I still feel the UN and its basis, the Charter, have the possibility of guiding the world in all its aspects.

But the leaders of our world must give up selfish nationalism. In democracies, electors must take the state of the world into account when voting for their leaders. All media, including social media must emphasize that the world is in danger but can be saved by the concerted action of all and at all levels.

Will the current danger of COVID 19, which has been universally felt and will continue at least until a vaccine is found, induce the necessary mentality changes? This is my hope, but alas, not my certainty.

Photo: The first session of the United Nations General Assembly opened on 10 January 1946 at Central Hall in London, United Kingdom. This was Robert's first day at work c. UN Photo/Marcel Bolomey.