This year, as the United Nations turns 75, the world is in crisis.

When the UN was conceived, it was met with true optimism about its potential to generate genuine, collective commitment to peace and stewardship of the world. Yet, in so many ways, it has failed to live up to its aspirational goals of peace, development and human rights for all.

The Organization was created to deal with global challenges – such as conflict, health, economic justice and the environment. These issues are all inter-connected, but they have been siloed within the UN, seriously curtailing efforts to deliver tangible progress for “We the Peoples”. In its worst moments, Member States have allowed corrupt and selfish interests to paralyse its ability to enact any change at all.

COVID-19 has cast a harsh spotlight on these issues. The pandemic has shaken us all and given us reason to pause. Stark divisions and inequities – and the structures that produce and uphold them – are now more visible than ever. And the crisis has underscored that issues as seemingly disparate as climate change, gender-based violence and the economy are all critically linked. For many years, we have unpacked all of these issues and put them in separate containers. This moment requires us to recognise that those issues are linked in ways one cannot overstate.

In my early days as an activist in Liberia, I saw that the impact of conflict on women’s lives is a reflection of their situation during peacetime. This is something I have carried with me throughout my life – and it is not merely true of conflict and crisis, when inequities are magnified, and our institutions’ weaknesses are laid bare. Rather, it is grounded in how our systems and institutions are designed to function.

Who would have thought that in the midst of a health pandemic, we would be talking about gender-based violence reaching an all-time high? For those of us that have seen first-hand how women’s safety, wellbeing and health are consistently underfunded and deprioritised, it has come as no surprise. It is a reflection of these systemic failures.

This is just one glaring example of the urgent need for new ways of thinking and approaching the age-old problems that continue to haunt us. To do so, we need to evaluate the principles underpinning the divisions among and within member states, and among and within communities, whatever the cause. And we need to look at what solutions are possible – to bring about change and transformation collectively, and to imagine what institutions that are truly responsive to this reality should look like.

Over the last few months, we have heard calls from around the world for new global organisations. This is typical. When faced with a crisis, we look first to replace our flawed institutions, instead of reflecting on why they are flawed and asking: “Where did we go wrong? How have we failed? How can we do it differently?”

My take is that even if we create a new UN – or a new NATO, a new AU, a new EU – we will still be faced with the same core problems.

We do not need to build new institutions; we need to build back those we have differently.

The big problems we are facing will persist if nation states and leaders around the world continue to rely on the same restrictive ideas about competition, greed and state sovereignty. This pandemic has made painfully clear that we can no longer just think of economies in the monetary sense. We must make care, solidarity and our common humanity central to them. One of the reasons multilateral cooperation is so vital at this juncture is that none of us are excused from these systems of militaristic thinking and greed.

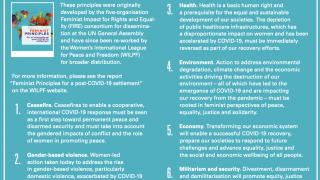

This autumn a group of international feminist organisations and movements came together to analyse the most pressing, interlocking issues facing the world right now, and to rethink our systems and societies. They developed six feminist principles for the future on: ceasefire, gender-based violence, health, environment, economy, and militarism and security. They demonstrate that we do ourselves a disservice when we fool ourselves into thinking that any single one of these issues can be separated from the others. Instead, we must put people and planet first. But what does that mean in practice?

Let’s take “ceasefire” as an example. From a feminist perspective, ceasefire means more than cessation of hostilities during armed conflict. It means the ability to imagine a future – and a pathway to that future – where all guns stop, where all violence ends, including police violence and state violence.

In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, these feminist principles build upon the common mantra among world leaders that we must “build back better” and lay out the foundations for building back differently.

The contrast, as I see it, is about having the courage to think outside the box and avoid repeating the same failed tactics that have destined us to arrive at this moment.

We must not continue falling into the same traps and abiding by the same so-called solutions, thinking they will lead to different outcomes.

Rethinking our institutions will also require us to rethink their leadership. Who is qualified to lead and why? Institutions need to work in partnership, with and respond to, the communities they serve, not merely what their leadership perceives as priorities or needs.

Now is the moment to take forward what civil society has been saying for the last 100 years: let us recognise that our fates are intertwined and humanity’s survival is based on solidarity, and put in place new ways of working and being together.

Amid the devastation, this year has also brought us hope that we can get there. On 24 October 2020 the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons received its 50th ratification. That means it will enter into force on 21 January 2021 – an historic victory. The push for the treaty – and for divestment, disarmament and demilitarisation – came from grassroots activists and civil society, many of whom have been immersed in this work for years, if not decades. This is an example of what can be achieved through the UN, when it is grounded in collective commitments, driven by the work of civil society and built to work for the people.

The feminist principles our group has outlined can support future further collective efforts of this kind. Women – especially grassroots women activists – are playing a role in pushing our limited and collective imagination in ways that cannot be understated. Such activism and radical visions have been essential in shaping the foundations of our institutions today, including the UN. In order to build back differently, women’s leadership, activism and expertise must be valued and acknowledged as central to our rebuilding.

In Liberia, we brought together women of different faiths and backgrounds to end the war. We had different mindsets and ideologies but we united around a singular vision. We came together.

This is the spirit that infuses everything I do. This is why I believe in our vision for building back differently – it is a journey that can inspire others around the world to join in new sorts of imagining. And in doing so, we can bring about the transformation that many of us crave – and demand.

Photo: Commemoration of International Women’s Day 2018 at United Nations Headquarters © UN Women/Ryan Brown.