Nisreen Elsaim shares her hopes for COP26

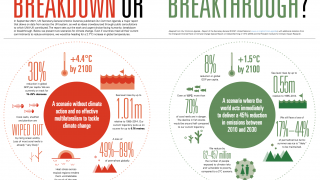

We often say there is consensus on the science of the climate crisis. But I’ve seen governments try to negotiate the science. When we were negotiating the Paris Agreement, many least-developed countries called for it to set a target of limiting global heating to 1.5oC. Even now, at just over one degree, we can see devastating impacts across the world – especially for the poorest and most vulnerable. However, some governments would not accept that and the Agreement ended up endorsing a two-degree target.

The IPCC report published in 2018 made clear what a huge difference that half a degree will make, and it was questioned so much that there was actually a negotiation session on the report at COP24 in Katowice. This is the biggest issue we face in climate diplomacy: that scientific evidence is treated as something political, something you can negotiate. But you can’t. You can negotiate agreements, finance, projects. But you cannot negotiate science.

Now here we are, three years on and the UN Environment Programme has published an emissions gap report that shows we are still not even close to meeting the 2-degree target. And the IPCC’s latest report made clear that things are getting worse.

So the to-do for COP26 in Glasgow is quite long. There are many topics where we need a turning point, which affect our livelihoods and communities, and the growth and health of our countries. For instance, we need to make headway on the processes for averting, minimizing and addressing loss and damage associated with climate change impacts. We urgently need to convert warm words on financing. We need an agreed definition for what climate finance is in the first place.

We need a breakthrough on the three mechanisms set out under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement on ‘voluntary cooperation’. The first would involve a country selling overachievement of its pledges (e.g. emissions cuts, reforestation or renewables) to countries that have fallen short. The second would create a new international carbon market, overseen by the UN. The third involves ‘non-market approaches’, for example, climate cooperation through development aid. Some believe that these mechanisms will help to raise ambition and spread finance, expertise and technology. Critics believe they would undermine the Paris Agreement.

G20 countries need to pledge – and deliver -- more. We cannot wait for 2050 to reach zero. We need to make USD 100 billion a year available. We realise the many challenges of the geopolitical situation. But we know the UK has the ability to influence countries and we are relying on this.

And we hope COP26 can be a turning point for the inclusion of young people. Right now, it’s hard to see that – with visa and accommodation challenges as well as COVID restrictions. Vaccine inequity, testing and quarantine will create logistical and financial issues for young people and participants from developing countries.

For people like me, climate change is not a choice. It is a reality. It is not a way to gain prestige or have a powerful position. It is an obligation arising from the impacts I have seen and from the dire predictions on the future.

So there is a lot riding on Glasgow. I really hope this will be the year we make it, because if we break now, I don’t know how long it would take us to recoup. We would lose valuable time. Young people will lose faith and could start taking different measures. We must succeed.

Photo: Nisreen Elsaim moderates the first meeting with the UN Secretary-General and Deputy Secretary-General, as the Chair of the Youth Advisory group. Credit: Masab Bashir.