On 24 June 2016, when the EU referendum results emerged, I asked a friend who had served in the UK’s mission to the UN how much he thought Britain’s position at the UN would be affected by the outcome. The answer came back promptly: “Our ambassador will claim no difference but the truth is otherwise. We have just lost a bloc of 27 other countries to lead.” In fact, Matthew Rycroft, the British ambassador to the UN at that time, told reporters that the UN was now “more important”, and that his job had become “even bigger”.

While it is understandable that a government implementing the referendum result has to put on a bold face, many Brexit triumphalists have gone much further. Henceforth, they say, we will be free to find our own way in the world, liberated from the protectionist and bureaucratic shackles of an inward-looking regional bloc. And some see us reclaiming our “rightful” place at the centre of the Commonwealth – whose members, they seem to think, have spent the last 40 years waiting for the UK to lead them once again.

In short, the past half-century of involvement in European integration is portrayed, implicitly if not explicitly, as a parenthesis that we can now put behind us, retrieving our historic destiny as a global seafaring power. This is fantasy, based on a highly selective view of British history and a willful disregard of changing global realities.

From the 18th to the 20th century, Britain’s global role was essentially an imperial one, at a time when we were able to translate technical advances into commercial and military (especially naval) superiority. We competed successfully with other European powers in the race to exploit, sometimes enslave, and subjugate non-European peoples. We told ourselves that we were “civilising” them in the process, brushing aside or disparaging their pre-existing cultures.

What we really did was destroy their social structure, partly by accident but often by design, molding new elites which absorbed aspects of our own culture – first to win power and prestige within a British-ordered universe, later to contest the premises of that order using its own values and language, and later still to live and work in Britain, contributing to our economy and making themselves an integral part of our society. In the words of the late Sri Lankan novelist and director of London’s Institute of Race Relations, Ambalavaner Sivanandan: “we are here because you were there.”

In the 20th century we retreated, for the most part not voluntarily but because the burden (economic and moral) of maintaining the empire came to outweigh the profits we derived from it. And one reason why that happened, or at least why it happened so quickly, was that we were embroiled in the two great European wars of self-destruction.

Thus the notion that European reconciliation and integration – the creation of a shared space of law and values – was an existential matter only for continental Europeans, but for us merely a trading arrangement that we could take or leave according to narrow calculations of profit and loss, was always absurd. And even more absurd is the idea that we can now resume a global role we had already lost even before embarking on the great European experiment – and to which no power in the 21st century, except possibly China, can or should aspire. Even my friend’s suggestion that the 27 other EU member states were there for us “to lead” – in the UN or anywhere else – sounds presumptuous.

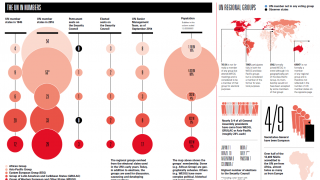

But Britain could have played a leading role in building an EU that was a new type of global power, one based on peaceful cooperation and shared values, one that plays a stabilising role in regional, and to some extent global, security without turning itself into a military superpower. Britain could have helped to make the EU a much stronger and more constructive leader at the UN, with contributions to peace operations, for instance, to match its contributions in development spending. At present, the African Union is the only regional organisation making a significant, and much-needed, troop contribution.

With populist leaders on the rise across the continent, this role now seems even more important. Alas, while politicians claim there will be no change in British influence at the UN, there is evidence of the opposite. Last year, the UK suffered a string of diplomatic setbacks at the UN, from failing to stop the General Assembly requesting an International Court of Justice opinion on the Chagos Islands situation to the defeat of British candidates in elections to the Court and to the World Health Organization.

There are many reasons for these setbacks. The plight of the Chagossians, expropriated by the UK, engenders solidarity among developing countries, most of which suffered colonial plunder at some point. Elections, meanwhile, are one area where the wider UN membership can push back against the disproportionate power of the Security Council’s permanent members. But it is telling that European allies backed or abstained from the Chagos decision, and that France does not appear to have suffered similarly in recent elections. At the very least, these issues have contributed to the perception that the UK’s influence has been waning for some time, and that the prospect of Brexit has hastened this process.

To deny this would be delusional, and would only leave British diplomats, at the UN and elsewhere, more exposed. To play anything that can reasonably be described as a global role, they will need to be much better resourced, and backed by strong policies and sustained interest from politicians in London.

The UK will need to accept that, at least for the time being, its much-vaunted role as a tempering influence and bridge between the United States and others at the UN is unlikely to work. The Trump administration is too unpredictable, and its actions are frequently at odds with British interests – for instance, when it seeks to weaken the very World Trade Organisation on whose rules Britain is banking as an alternative to EU membership.

There is already some evidence that the search for friends and partners outside Europe, and the need to avoid offending repressive powers from China through Turkey to Saudi Arabia, is making Britain more cautious about standing up for human rights around the world. This is unlikely to strengthen British influence or serve British interests in the long run.

On the contrary, if Britain really wants to be seen as a global power it needs to make itself a much more single-minded champion of universal values. It should use its permanent membership of the Security Council – currently seen by many as an anachronistic vestige of imperial power – to act as ally and spokesperson of those small and medium-sized states, inside and outside Europe, that have a stake not only in our system of multilateral institutions but in all the shared values and principles that underpin it.

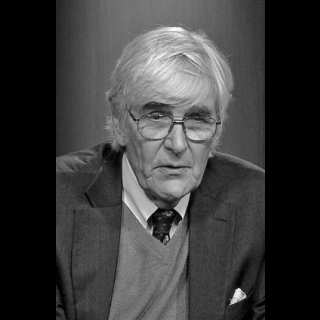

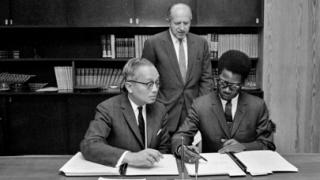

Edward Mortimer is a Distinguished Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford. He was Chief Speechwriter and Director of Communications under UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan (1998-2006) and was the Financial Times’ foreign affairs editor from 1987-98.

Photo: Left to right: Secretary-General Kofi Annan goes over a speech on Iraq with Edward Mortimer, Director of Communications and Head of Speechwriting Unit; Salim Lone, Director of the News and Media Division, Department of Public Information; and Fred Eckhard, Spokesman for the Secretary-General. March 2003. Credit: UN Photo/Stephenie Hollyman