There is a systemic shift afoot in the humanitarian world. This shift has been long in the making but we are only now beginning to recognise the changes in who is funding, organising, contributing to and delivering humanitarian aid.

The international humanitarian system has seen the rising involvement in humanitarian action of non-traditional donors, Southern organisations, regional organisations, diaspora networks, the military, the private sector and so on. As increasing numbers of new – or newly acknowledged – humanitarian actors take their place on the humanitarian stage, what does it mean for the traditional humanitarian system?

Looking historically, it is clear that this is not just a change in humanitarian action itself, but a change in our own perceptions or understanding of this work. The history of humanitarianism that we are most familiar with is that of the formal system – the beginnings of the Red Cross movement, the establishment of the UN agencies, as well as their forerunners in the League of Nations, and the creation of Western NGOs. But this is far from the whole picture of humanitarian action, both today and in the past.

“We’re not new actors. We’ve been around for decades,” said one non- OECD donor at a recent international humanitarian conference. Their agency had been funding humanitarian aid for more than 40 years, and yet it had only recently been recognised as a notable contributor.

However, the main issue at hand is not simply recognition, but rather a better understanding of how to engage with these rising and emerging actors in order to help bring about a more effective and inclusive humanitarian system, better equipped to deal with the challenges of today and tomorrow.

Traditional donors are keen to understand how to engage with these unfamiliar faces. Indeed, during another recent meeting of humanitarian donors and agencies, one delegate asked: “So how can we bring these new actors into the tent?” While this may seem like a fair question to many established players, it misses a more fundamental point.

Rising global actors do not aim simply to supplement the traditional humanitarian aid system. Many are looking instead to develop their own mechanisms and approaches when responding to humanitarian crises. There is a reluctance to join existing multilateral networks as the current system is seen as inadequate, bureaucratic, cumbersome and cost-ineffective – issues that this sector has grappled with for decades.

Working outside of the traditional system can allow organisations to respond in a flexible and dynamic manner, particularly in terms of funding processes. However, this departure is not without its problems as multiple, uncoordinated mechanisms can make it almost impossible to construct a coherent and accurate picture of effectiveness and accountability across all actors engaged with an issue.

Another key issue the humanitarian sector will have to address is partnerships. Partnerships between international and local organisations have often been criticised for their asymmetries of power and a lack of respect on the part of the global players for local knowledge, culture and capacities. Many partnerships are in essence sub-contracting agreements, with large international NGOs delegating work to smaller local organisations and then claiming the credit.

Sub-contracting aid work to local agencies is not intrinsically problematic. In today’s crises, such as Syria, many local organisations have better access to the communities in greatest need. But these relationships should be openly recognised, and partnerships made meaningful. If traditional humanitarian actors fail to embrace the contribution of emerging and rising actors, the former risk being excluded from the process of reshaping the future of humanitarian responses within this new landscape.

These are all issues, challenges, questions and dilemmas that the humanitarian sector must examine in coming years. In 2016, the first World Humanitarian Summit, will take place, under the auspices of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The Summit will seek to “make humanitarian action fit for the challenges of the future by broadening and deepening partnerships to assist those in need”.

In order for this meeting to achieve this aim, a wide range of humanitarian actors must input into the process. Together they can help bring about a more inclusive and effective architecture that reflects the true diversity of humanitarian action today.

It is difficult to predict what the future of humanitarian action will look like but, without a doubt, these new, non-traditional, emerging and rising humanitarian actors have a significant role to play. That is something to look forward to, to offer better support to those affected by crises today and in the future.

Sara Pantuliano is the Head of the Humanitarian Policy Group at the Overseas Development Institute, the UK’s leading independent think tank on international development and humanitarian issues.

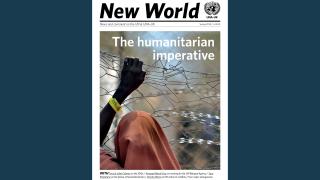

Photo: Volunteers for Kuwait Patients Helping Fund prepare a mixture for malnourished children, to be distributed by the World Food Programme at a camp for displaced persons in Darfur, Sudan. © UN Photo/Albert González Farran