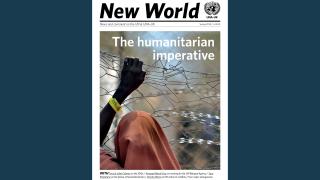

Since the last issue of New World went to press in October 2013, the humanitarian landscape has shifted significantly. In November, the strongest typhoon ever to make landfall devastated parts of the Philippines. By December, the Central African Republic (CAR), which experienced a coup last March, descended into violence which the UN has described as constituting crimes against humanity. The same month rivalries in South Sudan turned into full-scale clashes between government and rebel forces, with civilians in the crossfire. And in January, the UN announced that due to the increasing difficulties of verification, it would stop counting the dead in Syria.

Of course, these four crises did not spontaneously emerge onto the international agenda (see our feature for a snapshot of these situations). The CAR and South Sudan have both fared poorly on the UN Development Programme’s Human Development Index; the Philippines was already dealing with the effects of another natural disaster, an earthquake in October 2013 which affected millions; and Syria’s conflict is deeply embedded in historical grievances and much wider regional changes. As Deepayan Basu Ray asks in his opinion piece, what more can be done to effectively coordinate humanitarian relief and longer-term development work, where clearly both are vital to a country’s sustainable recovery?

Nor should we forget that these situations, though top of the UN’s list of humanitarian concerns, represent just four of the world’s current crises. The UN website www.reliefweb.net counts 58 countries as experiencing ongoing crises or disasters (see Alexandra Buskie’s web exclusive on how the UN defines such emergencies). How much we know about these other situations often depends on press coverage.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has for years endured a humanitarian crisis which drops in and out of the mainstream media’s interest. Whilst Yemen, where conflict, an economic crisis, and rising fuel and food prices have left nearly half the country food insecure, likewise merits very few mentions.

What our four “major emergencies” do usefully demonstrate, however, is the range of common challenges a humanitarian crisis can present – whether natural or man-made – and the exceptional efforts of the UN and its partners in addressing them. From how to deliver urgent supplies to those in need in a volatile and dangerous setting, to ensuring the protection and security of a scattered civilian population, or the deeper-rooted problem of assisting a refugee host community whose already scant resources and ailing infrastructure are stretched beyond their limits. Each would be worthy of its own issue of New World.

These emergencies will no doubt absorb much of the UN’s time and attention over the course of the coming year and beyond. In the main essay, Charles Petrie, former chair of the Panel of Experts, which assessed the UN’s actions in Sri Lanka, reflects on the lessons learned from that conflict and looks at what role there is for the UN in current and future violent crises.

As the events since last October have shown us, perhaps the most important issue for the humanitarian community is the need to adapt in this fast-changing landscape. Sara Pantuliano looks at how the system must evolve if it is to address these crises, meet their challenges and better serve those people caught in the middle.

Hayley Richardson is Policy & Advocacy Officer at UNA-UK and editor of New World. You can follow her on Twitter @hayliana.