Anniversaries are moments for both celebration and reflection. In 2020, we have been observing the anniversaries for the UN’s 75th year, as well as the 20th anniversary of the Women, Peace, and Security agenda, and 25 years since the Beijing Gender Equality Plan for Action. Both landmark developments for women’s rights at the UN have had a longevity and sustained commitment, but both are more unmoored and under threat now than could have been imagined 25 years ago.

A key element of the UN’s effectiveness is its leadership, and many of its leaders have been justly celebrated. In recent years there has been growing support for a more diverse and gender-inclusive cohort of senior leaders at the UN, including a strong push to elect a woman Secretary-General in 2016, and the launch of a new Gender Parity Strategy in 2017. Additionally, we are in the shadow of a global crisis of epic proportions, in which leadership matters more than ever. Effective leadership that represents and deeply understands the challenges that societies are facing is critical in managing the multidimensional risks that COVID-19 has generated—risks that affect everyone, but have disproportionately impacted women and girls.

In order to tackle issues of representation it is vital to understand the scale of the challenge. Until now it has been difficult to collect relevant data—high-level appointments are sensitive, and highly political—diminishing efforts to understand whether or not progress is being made.

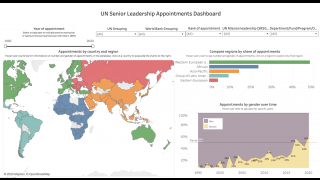

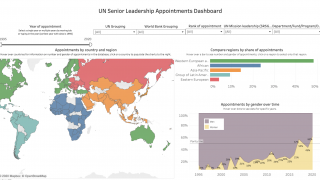

This is why the NYU Center on International Cooperation, in collaboration with the NYU Center for Global Affairs, recently launched a UN Senior Leadership Appointments Dashboard. The dashboard analyses the 1,300 senior appointments for which there are UN press releases from October 1995 until present. Our analysis provides data on trends regarding the pace at which the UN is working towards its commitments to more balanced representation—not just in terms of gender, but also across other dimensions such as nationality, UN regional groups, and other characteristics of senior leaders.

What are some of the emerging findings? First, without a doubt, having an active and engaged Secretary-General, alongside an experienced team managing the implementation of the Gender Parity Strategy, has resulted in a sea change of women’s representation at the highest levels of the UN. The trend from 2017 to present on women’s representation in leadership vastly outpaces the period going back to 1995 (and we can assume, before that). Before 2017, there wasn’t a single year in which women’s share of appointments exceeded 37% (much less parity at 50%), and in some years there is no press release announcing the appointment of even a single woman to a senior role. Yet from 2017 to present, the average has exceeded 50%, and in some year by quite a bit (57% in 2017 and 62% up to October of this year).

Even in the most difficult professional contexts to attract and maintain female leadership—UN peace operations, which operate in some of the most fragile countries in the world—there has been a marked improvement, including all-female leadership teams for the first time in places like Iraq, Cyprus, and Afghanistan this year alone. From 2017 to October 2020 women represented nearly 50% of all such appointments—a near-instant doubling of the previous trend of 22% from 1996.

The story on gender—although important on its own—also intersects with the one on nationality and region. And here we see that too many of the recent gains, particularly in the UN peace operations contexts, have gone to European and North American women, rather than women from the Global South. This gives a good guidepost for both enhancing the ongoing reform processes regarding senior appointments, and also in galvanizing Member State support for a more representative leadership cohort overall. In general, what is known as the “Western European and Others Group” at the UN, comprised of mostly Western nations, has claimed nearly 50% of all top appointments since 1996—in spite of the fact that they have only 20% of the world’s population.

Of course, much still needs to be done to understand the effects of this more inclusive representation at senior levels is translating to practice and effectiveness of institutions. But if we compare the leadership cohort of 2020 even to that in 1996—much less 1945, if we had the data—the changes are dramatic in terms of better reflecting the variety of faces making up our global population. But we should not be complacent; fostering more diverse and inclusive institutions in hard, long-term work. It requires our ongoing engagement and support, especially on practical ideas for reforms that will continue to move the needle.

Photo: A screenshot showing the UN Senior Appointments Dashboard.