In his first address to the General Assembly, US President Trump used the S word – sacrosanct “sovereignty” – 21 times, drawing loud applause from such human rights champions as Myanmar, Venezuela and Zimbabwe. Commentators rushed to lament the demise of Western liberalism and its 20th-century offshoot: the United Nations. So far, so familiar.

Except that the UN has never been merely a side project of its most powerful member state. Recent research by scholars such as Amitav Acharya, Eric Helleiner, Andy Knight, Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink shows the extent to which Southern agency has been a genuine but essentially underappreciated source of global norms, and that we need to set aside the traditional – and often convenient – narrative that the UN in particular, and the post-Second World War system more generally, were imposed by the West on “the rest”. The contributions of China and Imperial India in the 1940s, for example, to early efforts to pursue war criminals and to determine the post-war direction of assistance to refugees, and of trade and finance, complicate considerably this facile storyline.

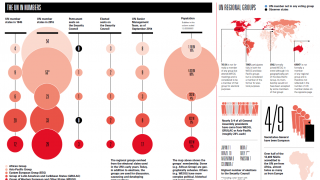

To be sure, deliberations about the future UN occurred before rapid decolonisation. Fifty states participated in the 1945 San Francisco conference whereas today’s UN membership is 193. Of these states, just four were African and nine Asian (see box in print version) although Latin America, independent since the early 19th century, was fully present and active in deliberations.

The shape and values of the UN were not simply dictated by the West – a misconception readily embraced by regimes in the global South that prefer not to be bound by universal human rights or security agreements. Indeed, rapid decolonisation is hard to imagine in the form and with the speed that it took place without the UN.

The more powerful countries, especially the US, had more to say in San Francisco, as during all international negotiations. But less powerful states influenced the agenda and advanced their own interests and ideals. The Latin American emphasis on regional arrangements in Chapter VIII of the UN Charter is one result. Chapters XI and XII on non-self-governing territories and trusteeship reflected the widespread views of recently decolonised states and other advocates of self-determination.

Even the structure of the Security Council – with its five permanent members and their veto powers – was the result of a more complex bargain than conventional wisdom holds. Every country had an interest in making sure that the major powers were committed to the new world organisation; their outsized role and veto were a Faustian pact to ensure that the UN would not go the way of the League of Nations.

SHAPING THE UN’S AGENDA

The Southern contribution to the UN’s agenda is often framed in terms of resistance to colonialism and superpower intervention. Despite their increasing heterogeneity, the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Group of 77 (G77) remain influential and continue to marshal arguments against neo-imperialism in UN debates on issues such as debt and trade.

Sustainable development

Their approach has been readily apparent in the development sphere. By the mid-1960s, decolonisation had nearly tripled the UN’s membership. Former colonies emphasised programmes to alleviate poverty and accelerate economic growth – a shift from the UN’s early focus on humanitarian relief and development as a means to underpin security. Development was a legitimate pursuit in and of itself. The UN World Food Programme, Conference on Trade and Development, and Industrial Development Organization were created in the 1960s. The 0.7% aid target was adopted by the General Assembly in 1970.

The East Asian Miracle challenged the standard Western formula of free trade, deregulation, privatisation and market liberalisation – as did the formula’s casualties in Latin America and Africa during the “lost decade” of the 1980s. But the notion of a more people-centred development – once radical and anything except music to certain Western ears – has, over time, become mainstream. At the UN Development Programme, Pakistan’s Mahbub ul Haq paved the way for a rights-based approach to development through the human development report and index, drawing on a partnership with Indian Amartya Sen’s work on capabilities.

Southern and indigenous actors were also early advocates of sustainable development. Activists such as Kenya’s Wangari Maathai, who founded the Green Belt Movement in 1977, joined the dots between environmental, societal and security concerns. Ten years later, the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights set out rights to development, a satisfactory environment and peace and security – a spread now reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Climate change, meanwhile, demonstrated the extent of division in what is often treated as a cohesive group. Smaller states, particularly islands, were vocal supporters of robust action to address what was, in their view, clearly an existential threat. Larger emitters vehemently resisted any form of binding targets, pointing to the overwhelming historical responsibilities of Western states for environmental degradation and emissions, and reigniting debates as to the level of assistance the international community should provide to emerging economies.

This standoff enabled reluctant Western states to drag their feet, individually and collectively, which stalled progress for several years. Yet, again, the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ is now widely accepted, and in fact is the basis for the Green Climate Fund. The 2015 Paris climate agreement, with its overarching targets, nationally determined commitments and peer review, is symptomatic of a trend in global governance towards more flexible, stakeholder-driven frameworks.

Human rights

Given the continual and contested debates on human rights at the UN – and the glee with which media outlets report that a “notorious human rights abuser” (almost always a developing country) has been elected to a rights-related body – it is a pity that the Southern contribution to international laws and norms is so often overlooked. At the San Francisco conference, South American women – notably Brazil’s Bertha Lutz, Uruguay’s Isabel P. de Vidal and the Dominican Republic’s Minerva Bernardino – successfully lobbied to include language on gender equality in the Charter. During the drafting and adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Lebanon’s Charles Malik and the Philippines’ Carlos P. Romulo were vocal proponents and defenders of the universality of rights.

Many developing states embraced civil and political rights as part of the struggle against colonialism and racism, and these rights continue to inspire the powerless and drive civil society movements in the South. They also supported economic, social and cultural rights more enthusiastically than some Western states, who were wary of the Soviet Union’s co-optation of these rights. And they took the lead in promoting group and collective rights.

Latin American states championed issues such as LGBTQ+ rights and action on enforced disappearance and torture. African states pioneered advances in child rights and natural resources. Human rights within the UN are what Sarah Zaidi and Roger Normand called the “unfinished revolution”; despite violations, they are a revolution nonetheless.

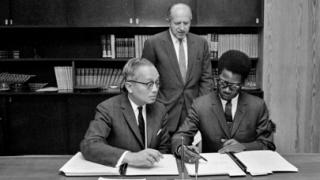

Fuelled by developing states, UN action to end apartheid in South Africa helped to reframe the principle of non-interference in states’ domestic affairs. While non-intervention was the basis for the Charter’s Article 2 and remains a popular shield for Southern (and Northern) governments, they have also been willing to act on the most contentious of issues – preventing mass atrocities. Sudanese diplomat Francis Deng recast the concept of sovereignty as responsibility, which subsequently was incorporated into the “responsibility to protect” (R2P) norm. Leaders such as Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo argued in favour of intervention, which was incorporated in the African Union’s (AU) Constitutive Act. The late Ghanian Secretary-General Kofi Annan pushed for the adoption of R2P at the 2005 World Summit. African support was critical to the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 1998.

While an alleged plan for AU withdrawal received much recent media attention, only Burundi has actually left the ICC, and many AU states have reaffirmed their support for it.

Peace and security

In peace and security too, the South’s role has traditionally been downplayed. While the Security Council continues to hog the limelight, with its glaring lack of African and Latin American permanent members, developing countries have in recent years provided an overwhelming number of UN peacekeeping troops (see box in print version). Indeed, “you lead, we bleed” is a common criticism of the divisions between the countries that mandate and fund peace operations, and those that send soldiers into harm’s way. Some have gone so far as to describe contemporary UN peace operations as a “Third World Ghetto”.

On page 9, Dan Plesch writes about the role of Southern countries in pushing forward arms control and disarmament initiatives. South Africa was the first state to voluntarily give up nuclear weapons, followed by Argentina, Brazil and Libya. Countries such as Lebanon and Mozambique took the lead on

banning landmines and cluster munitions (although big manufacturers from the North and South alike fiercely resisted these efforts). More recently, developing countries have increased efforts to boost the role of the General Assembly in tackling peace and security issues when the Security Council is, as so often, at loggerheads and missing-in-action.

CHANGING DYNAMICS AT THE UN

Developing countries have joined forces at different stages in the international arena to increase their voices, including through the NAM and G77. Over the past decade, a new twist has been added, the visibility of “emerging” or “rising” powers.

The term refers to countries whose policy elites are able to draw on economic and other sources of power to project influence within and outside their immediate neighbourhoods, and that play a substantial role in the call for global governance reforms. This label is problematic and should be contested, just like the terms “global South” and “Third World”. They reflect specific perspectives on development and historical experiences at specific moments in time. Despite their analytical flaws and misleading connotations, however, they matter in international politics and to the deliberations – some would say “theatre” – on various UN stages.

It is unnecessary to exaggerate either the shadow cast by the West, or what Amitav Acharya calls the “hype of the rest”, to see that the role of rising powers in global governance is changing the landscape. They are asserting their growing role as providers of development co-operation and as critics of the existing architecture for global economic governance. Both individually and through new alignments such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), emerging powers are engaging more directly in key normative debates about how major institutions could and should contribute to today’s world order.

Their composition is admittedly puzzling. The BRICS grouping, for instance, includes two permanent members of the Security Council – one a former superpower, the other the world’s second largest economy. They are authoritarian but their partners are democracies. They are hardly shut out of global decision-making but they are included amongst a slew of countries that have been described as rising or emerging (including Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand and Turkey) and that align themselves in seemingly endless configurations (BRIICS, BASIC, IBSA, MIST, etc.).

A NEW ERA OF GLOBAL GOVERNANCE?

The reality of a more multipolar order has renewed debates about the need to update our global governance system and thinking about how it should operate, as ever more countries grow unwilling to be “rule-takers” and aspire to be “rule-makers”. But too many states still accept the Anglo-American mythology, or peddle it as a justification for distancing themselves from uncomfortable aspects of the “old order” and its 1945 institutions.

A clearer appreciation of the actual history of the United Nations as a genuinely multilateral, if not always equitable, endeavour, could provide the basis for a new internationalist – perhaps even post-national – approach in which the definition of vital interests would expand to include perspectives and calculations about national interests that go beyond borders. This approach is urgently needed – and more suited to solving global problems than the ‘us-versus-them’ template and predictable performances that characterise what customarily passes for international negotiations in various UN theatres.

The second edition of The Oxford Handbook on the United Nations, co-edited by Weiss and Sam Daws, and including a chapter by Samarasinghe on human rights, is featured on the back cover.

Photo: Kenyan peacekeeper with Croatian family in 1992 © UN Photo/John Isaac