In October 2019, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres informed Member States that the organization was facing its most challenging liquidity crisis in decades. The UN Secretariat’s core (regular) budget was in overdraft to the tune of half a billion dollars.

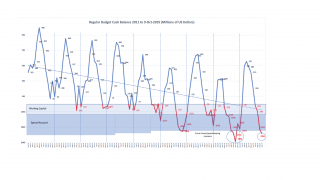

The UN relies on assessed contributions from its 193 Member States to fund its activities. Variations in the way Member States pay means that the Secretariat annually goes from a healthy bank balance in the spring to just about managing in the autumn.

Over the last few years the financial situation has progressively gone from bad to worse with the Secretariat coming perilously close to exhausting all reserves.

The Secretary-General has only limited reserves to manage cash deficits and ensure staff are paid and the organization keeps afloat. Recent trends suggest the reserves are looking increasingly insufficient to get it through this annual financial crunch.

This year he has taken all emergency measures within his powers to manage the liquidity crisis and get through to the end of 2019. He has limited official travel for Secretariat staff to the most essential. He has postponed purchases of goods and services, delayed spending on facilities management and implemented measures to reduce utility usage. Most controversially from mid-October he put a stop to all events outside of official working hours.

While these extraordinary measures should help keep the UN afloat this year, they could have the impact of worsening the crisis in the medium term. Delaying necessary spending such as repairs to facilities will only increase the pressure on the UN budget in the coming years.

The cause of the crisis is late payment of contributions by Member States. Each of the 193 Members of the UN is required to contribute to the UN’s budget in line with their capacity to pay. This ranges from 22% of the UN budget for the United States to 0.01% for Least Developed Countries. Each January the Secretary-General sends assessment letters to Member States who in turn are required to pay their bill within 30 days. Many Member States pay on time - and should be commended for doing so - but late payments are becoming an increasing problem. By October 2019, 65 Member States had not yet paid their assessment to the regular budget in full, 13 more than the year before.

Over 90 percent of the outstanding contributions are owed by just three Member States: the U.S., Brazil and Argentina. At the beginning of October, the U.S. owed more than $1 billion to the UN Regular Budget. Since the 1980s, U.S. congressional budgeting cycles have meant the U.S. has paid its annual Regular Budget assessment late. In addition, for the last three years the U.S. has also withheld a share (approximately 5%) of its annual contribution. Further, bureaucratic challenges within the US administration have meant that the contributions it has made have been paid later than usual. Fortunately, a large chunk of the US Regular Budget contribution for 2019 finally started coming in at the end of November.

The deterioration in the pace of US payments has been compounded by delays in contributions from other countries, in particular Brazil and Argentina. In recent years’ domestic economic woes, growing budget deficits and currency depreciation, have meant that both countries’ contributions to the UN Regular Budget have become more erratic.

Outstanding Contributions to the UN Regular Budget as of 4 October 2019 and 4 December 2019:

- USA: Oct: $1,055m Dec: $491m

- Brazil: Oct: $143m Dec: $143m

- Argentina: Oct: $52m Dec: $47m

- Other countries: Oct: $137m Dec: $102m

Domestic dynamics within these three countries are unlikely to change dramatically in the coming years and the liquidity challenges faced by the UN will be even greater in 2020.

This growing crisis should not come as news to the UN Membership. Guterres has diligently brought the financial pressures he faces to the attention of Member States over the last year, urging them to adopt measures that would help him better manage the liquidity. Unfortunately, his pleas have gone unheeded to date, with Member States unwilling to agree reforms such as increasing the level of reserves available to the Secretary-General.

Without Member State action, the liquidity crisis facing the UN are on course to be more severe in 2020 with a real danger that UN ability to function will be compromised. Member States, including the UK, need to use the next six months to work out how they can help the Secretary-General manage this crisis. This may require thinking outside the box by for example allowing him to borrow commercially or from other parts of the UN.

Photo: A staff member of the UN Facilities and Management Service adjusts the clock at the Security Council chamber © UN Photo/Loey Felipe