In 2015 the Association, like the UN, turns 70. This article traces UNA-UK's story, from the League of Nations Union to its current campaigns on UK and UN policy.

UNA-UK shares its birth year with the United Nations, and like the UN, it is a second take. The Association’s roots lie in the League of Nations Union (LNU), formed in 1918 to promote international justice and collective security through the establishment of the League of Nations. It became the largest and most influential peace organisation in the UK, with nearly half a million members.

The LNU played an important role in British interwar politics, and prominent Liberal and Conservative politicians – including foreign secretary Edward Grey and Lord Cecil, one of the League’s architects – were heavily involved. In 1935, it conducted the ‘Peace Ballot’, which surveyed 11 million people – 38 per cent of the adult population – on their attitudes to the League’s aims and objectives. The LNU felt that Britain’s growing isolationism had to be countered by a massive demonstration of support for a UK foreign policy in which the League played a central role.

The results of the ballot, which showed overwhelming approval for collective peace and security, were widely publicised. Some commentators have suggested it led to the Axis powers believing Britain to be unwilling to go to war, even though those voting in favour of military action to counter aggression outnumbered those against by three to one. Winston Churchill said it showed that Britons were resolved to go to war for a righteous cause.

The failure of the League to respond to conflicts such as the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, and the absence of key states – the US refused to join; Germany, Japan and Italy left; and the USSR was expelled – made clear the limits of international organisation without full participation. LNU membership plummeted.

Planning for a successor – to the League and the LNU – began while the Second World War was still raging. On 7 June 1945, three weeks before the United Nations Charter was opened for signature, UNA-UK held its first meeting. On 10 October, a fortnight before the Charter entered into force, the Association was inaugurated in a packed Royal Albert Hall. Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Anthony Eden MP and Megan Lloyd- George MP addressed the crowds. Lord Cecil remarked: “the first great experiment is over – we must work for the second.”

The Association absorbed much of the LNU’s work, resources and staff. In the late 1940s, it focused on enshrining the values of the UN Charter in the hearts and minds of Britons and on calling for strong UK support for its work. This included a generous approach to resettling refugees.

In the 1950s, it started collections to support the UN’s work, effectively doubling the UK’s contribution to UNICEF in 1953. It also sent volunteers to rebuild houses in Austria and Germany. UNA-UK’s support for decisive UN action in Korea led to an exodus of pacifist members, some of whom returned in later years. By the 1960s, the volunteer programme had grown, with 30 overseas camps and an official placement scheme. Disarmament and human rights became major concerns for the Association, which also began to discuss environmental matters.

In the 1970s, UNA-UK campaigned tirelessly for overseas development aid – our call for the UK to meet the 0.7 per cent target was only met in 2013. It also organised a series of events ahead of the first UN World Conference on Women.

The 1980s saw UNA-UK lead the “Let’s Freeze this Winter” campaign, which lobbied hard against the deployment of missiles by NATO and the USSR. After the UK withdrew from the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Association set up an informal all-party group of MPs to work for its re-entry, eventually achieved in 1997. The national commission for UNESCO was also housed within UNA-UK.

In the 1990s, UNA-UK was heavily involved in education work, with model UN events and teaching resources linked to the UN’s 50th anniversary. It also celebrated the end of apartheid – a longstanding priority for the Association. The first half of the next decade was devoted to campaigning against the Iraq war, and the second to arms control, with UNA-UK playing a key role in reversing the UK’s position on cluster munitions, paving the way for a global treaty.

UNA-UK’s mission in 2015 remains the same as it was in 1945: enshrining the values of the UN in the hearts and minds of the public, ensuring strong UK support for the Organization, and advocating ways to make the UN more effective.

Three recent campaigns exemplify this approach: first, our successful push to keep teaching about the United Nations and global citizenship in the national curriculum for England. Second, our UK general election campaign, which called for serious discussion of Britain's role and set out a foreign policy manifesto, outlining 10 ways in which the UK could act as a force for good, such as greater engagement with UN peacekeeping and a strong commitment to human rights. And third, the 1 for 7 Billion Campaign, a global initiative spearheaded by UNA-UK, calling for a fair, open and inclusive process to select the UN Secretary-General.

70 years ago, UNA-UK was founded to serve as a bridge between the UN and people in this country. Today, this mission is more important than ever. From climate change to pandemics, terrorism to displacement, the challenges facing the world require an effective UN, supported by an engaged UK Government and public that understands how much global solutions will deliver for them.

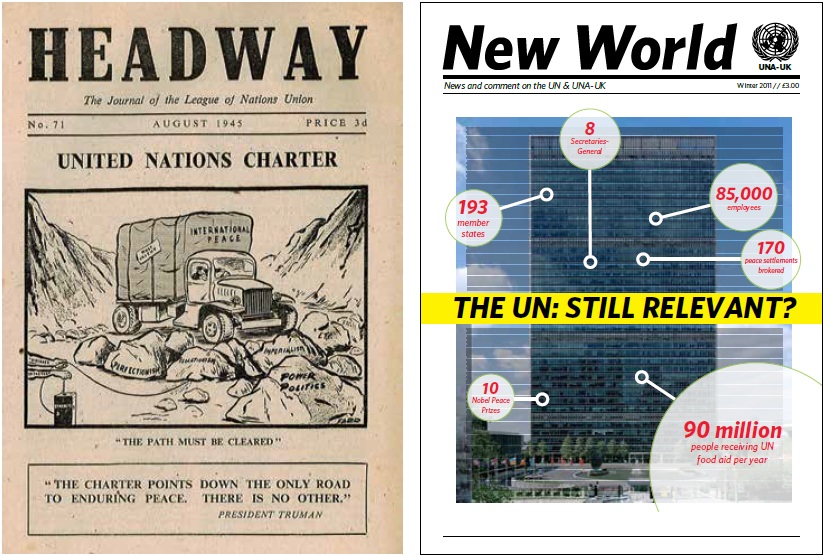

Photo: Headway cover (August 1945) and New World cover (Winter 2011). UNAUK's magazine has provided news and comment on the UN and UK's relationship with it since the Organization's inception