There is no silver bullet for UN reform but a better way to select the Secretary-General comes close.

How can we make the UN work better? The short answer: political will. It is the UN’s member states that call the shots, setting the Organization’s priorities and budget. If they chose to, they could look beyond narrow national interests and give the UN the authority and resources it needs to serve the long-term interests of the world.

This is a big “if”, seemingly so insurmountable that typical answers to this question focus on the UN’s structures, not its members' policies, notably enlargement of the Security Council. While more representation would add to its legitimacy – an important consideration – a larger membership may not make the Council more effective or progressive, if the voting records of regional powers, the likely candidates for new seats, are a guide.

Readers may disagree. In any case, however desirable the reform, the debate remains academic. Member states cannot agree on what a new Council should look like. Even if they could, changing the Council’s composition requires amendment of the UN Charter, which in turn needs the backing of its five permanent members (P5). They are in no rush to do so.

Small but mighty

A smaller reform, which doesn’t require Charter amendment, could have more immediate impact: a better way to select the UN Secretary-General. The next appointment is due in 2016.

Changing a recruitment process may not sound transformative, particularly for a role described by the Charter as “administrative”. But improving this one would have great practical and symbolic value.

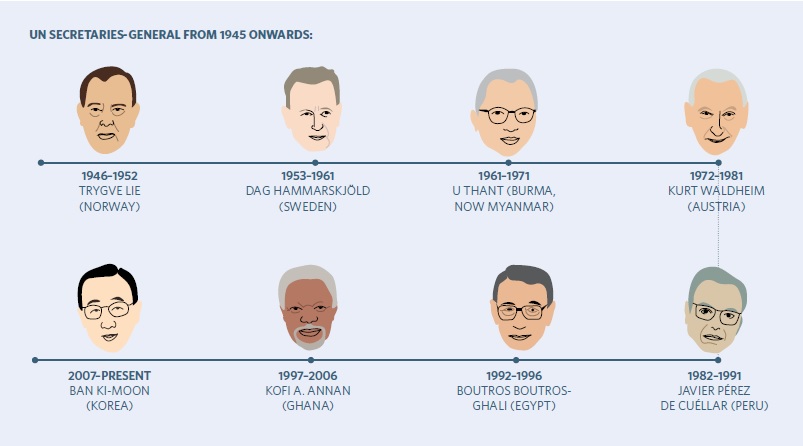

In 1952, Trygve Lie, the post’s first incumbent, resigned. The USSR had turned on him after he backed UN action against North Korea. The US, meanwhile, had begun to hunt for communist spies at UN headquarters. He thought his position untenable. In his valedictory, he spoke of states’ duty to leave no door unopened in seeking to use the UN’s resources for peace, noting that one such door, the office of the Secretary- General, had been closed and “not because of me”.

Lie’s words capture the perils and potential of the role. To be effective, Secretaries-General must maintain the support of member states, particularly the big powers. But if this balancing act is achieved, they can manoeuvre within the parameters of politics and the Charter to great effect.

One for seven billion

From the outset, states recognised that the Secretary-General would be more than an administrator. The 1945 UN Preparatory Commission noted: “The Secretary-General, more than anyone else, will stand for the United Nations as a whole. In the eyes of the world … he must embody the principles and ideals of the Charter.”

The Secretary-General is a voice for the poor and marginalised, a voice that can transcend national interest. By carving out positions distinct from member states, he or she can preserve the UN as a symbol of hope.

The Secretary-General can enhance the UN’s impact across the board: coordinating efforts to tackle cross-border challenges; encouraging action on situations that lack big-power interest; making smart appointments to key UN positions; pioneering norms; and building partnerships.

Peacekeeping, for example, was developed by Lie and his successor, Dag Hammarskjöld, who also expanded the Secretary-General’s “good offices” function. In 1955, he secured the release of 11 US airmen imprisoned in China. U Thant, appointed after Hammarskjöld’s death, played a significant role in de-escalating the Cuban Missile Crisis.

More recently, Kofi Annan, Secretary-General from 1997 to 2006, brokered a groundbreaking – and lifesaving – deal with pharmaceutical companies to widen access to HIV/AIDS treatment. He is also credited for his advocacy of the “responsibility to protect” norm. Ban Ki-moon, the current postholder, has used the Secretary-General’s moral authority and convening power to champion LGBT rights and action on climate change.

Crucially, Secretaries-General can also play a pivotal role in preventing conflict and atrocities. The Charter enables them to bring to the attention of the Security Council any matter that may threaten peace and security. Their ability to do so would be enormously strengthened by a selection process that gives them a real mandate to act.

P5 stranglehold

The Charter deals with the process in one sentence: “The Secretary-General shall be appointed by the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council.” That both bodies play a formal role in the appointment is sensible, reflecting the realities of the Secretary-General’s operating context. But informal practices have skewed this balance, relegating the Assembly’s role to one of rubberstamping and increasing the P5 stranglehold.

Initially, proposals were made for the Council to put forward candidates for the Assembly to vote on by secret ballot. In its first session, however, the Assembly curtailed its own role, stating it would be desirable for the Council to proffer only one candidate and for debate in the Assembly to be avoided.

Current practice takes this to the extreme. There are virtually no established rules or criteria for the appointment. The Council makes its decision behind closed doors, sometimes before the wider UN membership knows who’s in the running. Even states elected to the Council are not in control. Agreement is usually the result of secret bargaining among the P5, a process that includes extracting promises from candidates, on positions in the Secretariat, for example.

Since 1997, states’ insistence on geographic rotation has restricted the talent pool to candidates from particular regions. The Eastern European Group is now asserting its claim. And no woman has ever been seriously considered for the role. Just three of 31 formal candidates in past elections have been women.

As it stands, the process is seriously deficient, out of step with modern recruitment practices and contrary to the UN’s principles of good governance. Above all, it is geared to selecting someone unlikely to rock the P5’s boat. While incumbents have managed to prove them wrong, imagine what more could be achieved if the process actively encouraged bold and visionary candidates.

What could be

A process that engages all states – and civil society – would give future Secretaries-General a stronger mandate. This would boost their ability to mobilise support for, and drive forward, the UN’s agenda.

A single term of office would further strengthen their hand, providing them with the political space to develop a long-term agenda. Freed from the constraints of seeking re-election, the Secretary-General would be in a better position to insist states take action to prevent conflict and atrocities, and to resist states when they ask the UN to take on poorly-resourced tasks or poorly-qualified candidates for senior UN positions. He or she might feel more able to say "no".

Last year, UNA-UK co-founded 1 for 7 Billion, a global movement of over 170 million people calling for a better process. The campaign’s proposals have widespread and long-standing support from member states.

A chance for change

Over 150 states have called for change ahead of the next appointment. Most gratifying for UNA-UK, the UK has taken up this issue within the P5. It has called for a process open to all member states, as well as civil society. The Non-Aligned Movement and the ACT grouping of reformed-focussed states have put forward concrete proposals, such as hearings with candidates. There is also support for a single term for postholders.

This momentum has resulted in pushback. Of all the things the US and Russia should be working on, they seem to be coordinating their opposition in the Security Council. Their attitude is short-sighted. The reforms on the table do not take away the Council’s role in the decision, nor the P5’s ability to veto candidates. They would simply inject some transparency into the process, helping to restore a modicum of confidence in the power structure the two countries are seeking to preserve.

In any case, they may find it difficult to prevent change. There is much the General Assembly could do without Council blessing. It could set out a timetable for the appointment and organise hearings with candidates. It could also request a public shortlist.

Secrecy, already fraying at the time of the last appointment in 2006, when candidates created websites and gave interviews, is near impossible today. Other bodies, such as the World Trade Organization, post CVs and vision statements on their websites. The International Labour Organization uses a video link so hearings can be observed.

And the Assembly could ask to be given a real choice, with more than one candidate put forward by the Council. It has taken decisive action in the past, for example, proposing Thant to fill Hammarskjöld’s unexpired term, when the US and USSR were unable to agree on a candidate. Again, other parts of the UN system provide an example: the World Health Organization Board is asked to nominate three candidates for the Health Assembly to consider, unless there are “exceptional circumstances”.

There is no silver bullet for UN reform, but a better way to select the Secretary-General comes close. It would signal that the UN is capable of change and give the wider UN membership a more meaningful role.

In this 70th anniversary year, the need for the UN is greater than at any time since the Second World War. States must use this opportunity to enhance its effectiveness and credibility, and reaffirm its global authority and popular appeal.

Go to www.1for7billion.org for more information