The Earth is the root and the source of our culture. She keeps our memories, she receives our ancestors and she therefore demands that we honour her… We have to take care of her so that our children and grandchildren may continue to benefit from her. If the world does not learn now to show respect to nature, what kind of future will the new generations have?*

The world’s 370 million indigenous peoples make up five per cent of the global population but 15 per cent of the world’s poor. They suffer markedly higher rates of landlessness, malnutrition and displacement, and have lower levels of literacy and access to health services. They are also among the first to face the direct consequences of climate change.

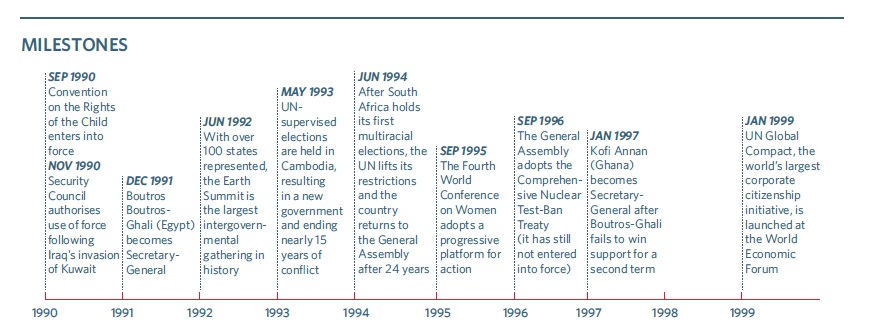

At the beginning of the 1990s, the UN looked set to make great strides towards addressing these issues. In 1990, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its first major scientific assessment. Two years later, an unprecedented number of world leaders and NGOs headed to Rio de Janeiro for the UN Earth Summit. The Summit led to the creation of three major conventions, on climate change, biodiversity and desertification, and eventually to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the first international agreement to set binding emission reduction targets for developed states.

Action on indigenous issues was also gathering steam. The General Assembly declared 1993 to be the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People, and the first International Decade began in 1995. After several years of work, the first draft of a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was completed, and discussions were held on establishing a Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, eventually created in 2000.

In the new millennium, progress slowed. It was only in 2007 that the General Assembly finally adopted the Declaration. It is not binding on states but four countries with substantial indigenous populations – Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the US – still voted against it. The Kyoto Protocol did not enter into force until 2005 and efforts to negotiate a successor agreement ended in disarray at the end of the decade. Today, prospects for the 2015 UN climate conference are more promising and the Declaration’s opponents have reversed their position. But the journey from agreement to implementation will be long.

Rigoberta Menchú Tum, a Quiché Mayan, has been at the forefront of indigenous rights and environmental activism for three decades. Her village in Guatemala was one of several hundred that was levelled to the ground in the 1970s. Her father, who was active in the Committee of the Peasant Union, was murdered; her mother and brother were tortured.

In response, Rigoberta became a campaigner. She was one of the first indigenous delegates to the UN and a member of the working group that drafted the Declaration. Later she served as a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. In 1992, she was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. Her fight continues.

*Rigoberta Menchú, Nobel Lecture, 10 December 1992

Photo: Young Kazakh shepherd riding a horse in Karkara pastures, Kazakhstan. Copyright UN Photo/F Charton