Security, peace and the control of military force is the area where thinking and approaches have changed most since the founding of the UN nearly 70 years ago. The UN Charter focused on a legal approach, requiring member states to settle international disputes by peaceful means and to refrain from the threat or use of force. In the case of threats of aggression, the Charter envisaged a succession of steps under the authority of the Security Council including blockades and severance of diplomatic relations, but, if these fail, calling on other states to provide armed forces for the “purpose of maintaining international peace and security”. It even envisaged a Military Staff Committee and the employment of forces under the strategic direction of the Security Council.

Within 10 years, Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary-General had shifted the emphasis from law to preventive diplomacy, under which the Secretary-General himself could use his good offices, even without Security Council approval, to negotiate between parties in conflict. Initially this was thought to require almost total secrecy but later this was somewhat relaxed. Preventive diplomacy had an important and dramatic if little known part in defusing the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 when U Thant, then acting Secretary-General engaged in behind the scenes diplomacy which helped avoid direct confrontations between the Soviet Union and the US, an effort which later elicited formal thanks from the two powers (this incident is described in Bertrand G. Ramcharan’s Preventive Diplomacy at the UN).

Though the UN’s work in the area of peace and security was hindered and restricted by the Cold War, this didn’t prevent further initiatives. Measures to link disarmament and development were proposed at the UN on a succession of occasions by France in 1955, by the Soviet Union in 1956 and by Brazil in 1964. The French proposal envisaged that all participating states would reduce their military expenditures by a certain percentage which would increase each year. A quarter of the resources saved by disarmament would be paid into an international fund for development in developing countries. These and other ideas were made a focus of the three UN special sessions on disarmament and development held in 1978, 1982 and 1988.

The most fundamental change came in 1994, after the end of the Cold War. The UN Development Programme’s Human Development Report proposed a fundamental shift to human security. Instead of countries concentrating on the protection of their geographic borders from other countries by military means, they should shift to a set of priorities focused on people– the protection of a country’s population from the various insecurities which affect them, internal even more than external. Such insecurities included food insecurity, health insecurities, along with environmental, personal, community and political. Gender violence was identified as a particular form of insecurity. Later the Human Development Report added financial insecurities and global crime, foreshadowing major problems of the 21st century. Human insecurities affect many more people in the world today than the traditional threats from war, even though war and civil strife continue to wreak havoc on millions of the populations in certain countries, including the record number of refugees who have fled for their lives.

Although criticisms of human security have been made, especially because of the difficulty of prioritising among the wide variety of threats which it potentially encompasses, the concept has gained increasing attention within the UN. Several sessions of the General Assembly have been held to debate the issues and at least 20 countries have prepared National Human Development Reports focused on human insecurities and the actions required to tackle them. Latvia is the country which has most systematically explored human security as it affects its own population. An in-depth questionnaire was used to assess the insecurities felt and experienced by men and women throughout the country, with those sampled asked to rank some 30 threats in order of importance. Health risks and the inability to pay for medical care emerged at the top of the lists of human insecurities, with loss of income and unemployment next. Threats from nuclear attack were rated among the lowest. (Even in Afghanistan, a report on human security found that lack of access to safe water was ranked higher than risks of terrorist attacks.)

Austerity programmes in recent years have greatly increased the risks and human insecurities experienced by many people in many countries. Although military expenditures have sometimes been reduced as part of economic adjustments, few countries have systematically considered the consequences in terms of human insecurity, let alone planned a human response. Human security thus remains a high priority for analysis and planning in all countries, developed as well as developing and an opportunity to bring a fresh perspective to issues traditionally considered in terms of weapons and armies.

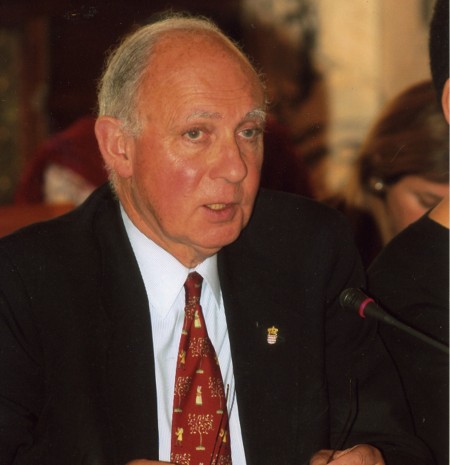

Richard Jolly is an Honorary Professor and Research Associate at the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, and was formerly a UN Assistant Secretary-General.

Photo: © UNA-UK. Sir Richard Jolly received UNA-UK's Sir Brian Urquhart Award for Distinguished Service to the United Nations in 2013.