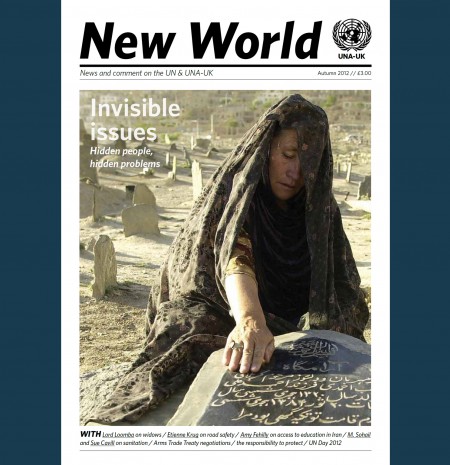

October marks an important anniversary for women’s rights activists. Twelve years ago, on 31 October 2000, the United Nations Security Council adopted a landmark resolution. UNSCR 1325 broke new ground in recognising the importance of women’s “equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security”. Since then, a further four resolutions – 1820, 1888, 1889 and 1960 – have called for action on sexual violence, provided frameworks for protection, and recommended global indicators to monitor progress for women in conflict.

These important commitments from the international community are a testament to sustained campaigning from women’s movements to keep women’s rights in conflict on the international agenda.

Yet as we mark another year since the first resolution, are women really at the heart of peace processes? The answer is a resounding no. In recent peace negotiations, women have represented fewer than 8% of participants and fewer than 3% of signatories. No woman has ever been appointed chief mediator in UN-sponsored peace talks.

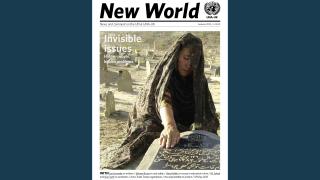

But a new report from ActionAid, Womankind Worldwide and the Institute of Development Studies, shows that women are doing vital work to rebuild communities after conflict. Researchers spoke to over 550 women and men in Afghanistan, Liberia, Nepal, Pakistan and Sierra Leone, and found that despite geographical, cultural and historical differences between the countries there are some important similarities.

First, women and men have different understandings of peace. Whilst men associate peace with the absence of formal conflict, and functioning governance structures, women tend to have a broader view which includes enough food for the household, access to healthcare and education, and an absence of violence in the home. As Saathi’s Bandana Rana, a member of the UN Women Global Civil Society Advisory Group, told researchers, “Women need security in their home, they need to sleep well in their beds. Violence can come from husbands, from neighbours, or from family members, domestic violence is a particular problem”.

Second, women are working collectively at the local level, taking practical action for peace. In Liberia, Maima* was supported by the local women’s forum to stand for election to the Parent Teacher Association, from where she was instrumental in rebuilding the school and increasing girls’ attendance. In Afghanistan, the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre has built a safe women-only space providing literacy classes, computer courses, and training in tailoring and agriculture. In Pakistan women described mediating within family disputes and convincing their children and relatives to not resort to violence.

Yet despite their clear contribution to peace in their communities women are still sidelined from national and international peace processes. Their unique understandings of conflict, and their particular needs and hopes for peace are missing from formal peace negotiations. Barriers including violence, inequalities in education, caring responsibilities, and women’s devalued roles as peacebuilders, means that men continue to negotiate and sign peace deals. But fair and lasting peace is impossible without the views of half the population.

From the ground up calls for a minimum of 30% representation to be guaranteed for women in all local, national and international peace negotiation processes. Furthermore, it recommends that at least 15% of all funds for peacebuilding be dedicated to advancing women’s rights and participation.

It’s time to honour the commitments set out in UNSCR1325 and put women at the heart of peace.

* Name changed to protect identity

Lee Webster is a women’s rights activist. She is Policy and Advocacy Manager for Womankind Worldwide, with a focus on women, peace and security. www.womankind.org.uk