Every year, almost three quarters of a million people die from armed violence, while millions more suffer indirectly. The insecurity arising from violence affects lives and livelihoods, preventing people from working and going to school, and adversely affecting trade, transport and basic services. A significant part of this suffering is due to the unregulated and irresponsible trade in arms, which puts weapons in the hands of criminals, insurgents and repressive regimes.

After years of campaigning by NGOs including UNA-UK, the UN General Assembly voted in 2006 to start work on a treaty to regulate the arms trade. The purpose of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) is not disarmament but control through legally-binding standards.

Last-minute blockage

Last-minute blockage

In July 2012, the six-year treaty making process culminated in a month of negotiations that, according to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, aimed to “agree a robust, effective and legally-binding ATT”. Until the final morning of the conference, agreement looked plausible. Then, at the eleventh hour, the United States, followed by a handful of others, including Russia, derailed the process by asking for more time to consider the draft text. They were able to do so because agreement depends on consensus – a much-criticised element of the ATT process.

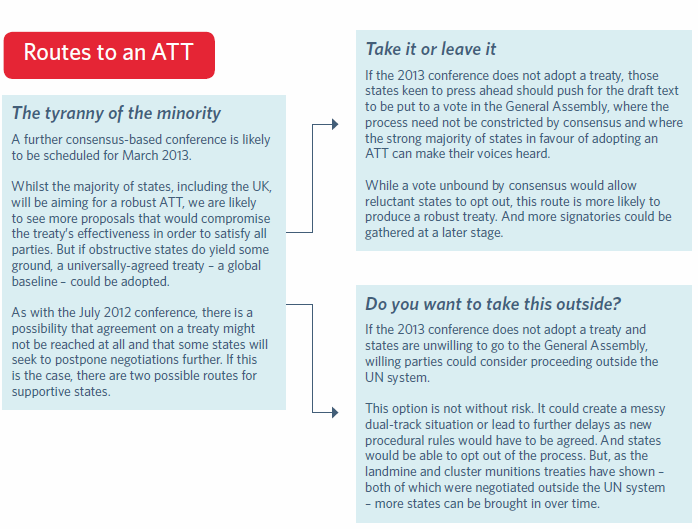

Although disappointing, UNA-UK remains confident that a robust treaty is within reach. Indeed, the head of the UK delegation, Jo Adamson, called the outcome “a pause, not a failure”. At the end of the negotiations, over 90 states issued a statement saying they are “determined to secure an Arms Trade Treaty as soon as possible”, and Ban Ki-moon noted that the conference had yielded “considerable common ground” for countries to build on. Negotiations now look set to resume at a further ATT conference, likely to be held in March 2013.

Why the delay?

On the surface, it is easy to surmise that the US – the world’s largest arms exporter – simply does not want a treaty. However, the country already has comparatively strong export controls and the draft text is based on best practice from regulations that exist in a number of states. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has noted that the ATT negotiations offer an “opportunity to promote the same high standards for the entire international community that the US and other responsible arms exporters already have in place”. Furthermore, the US delegation to the conference stated that it had no “core” objections to the draft text, which had been significantly weakened during negotiations to meet its red lines.

So why the delaying tactics? Many commentators believe that with the US presidential elections fast approaching, the Obama administration is loath to make any major international commitment, especially one arousing strong, albeit ill-founded, objections from the country’s pro-gun lobby which has erroneously linked the ATT to both domestic gun use and disarmament. It is likely that agreement on a text – whether or not the US actually signs up to it – will be used by the Republicans for political point-scoring. It appears that the US has diffused this tension by deferring any decision-making process to after the election.

It is, of course, worth noting that the US was not alone in delaying negotiations and that other states used its position as cover for their own objections to the ATT.

A blessing in disguise?

The inability of states to agree a treaty at the July conference was widely reported as a failure. Yet closer scrutiny of the draft text might lead campaigners to view it instead as a narrow escape. In the quest for consensus, many provisions had been weakened so significantly that the treaty under discussion is a far cry from the robust and effective mechanism that NGOs had hoped for.

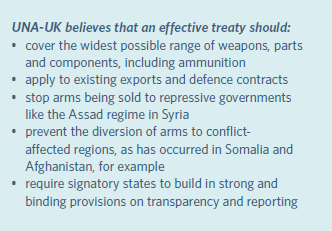

As it stands, the draft is not wide enough in scope, nor does it do enough to inhibit transfers where a substantial risk of misuse and diversion exists. There are three main areas of concern.

- It does not provide for adequate regulation of ammunition or the export of weapons in part or component form, and also exempts existing defence contracts.

- Given the impracticability of enforcement by a international body, an effective treaty must include strong, binding provisions on transparency and reporting, so that parliaments around the world can help scrutinise implementation.

- The provisions relating to preventing transfers from falling into the hands of human rights abusers are so weak that some believe it would take an imminent genocide (with evidence to prove it), before they are activated.

Had this watered-down ATT been adopted, we would now be dealing with the consequences of a lowest common denominator treaty unlikely to bring about the improvements we all desire. Every month that passes without a properly regulated arms trade is, of course, another month in which tyrants and criminals can acquire and abuse weapons with impunity. But given that it took decades to build the momentum and political will necessary for the ATT negotiations, there is no telling how long it would take to reopen discussions to improve an ineffective treaty.

Keeping up the pressure

The creation of a robust treaty without these weaknesses is not the quixotic ambition of NGOs and activists – it is the preferred outcome for the vast majority of UN member states. A weak treaty risks institutionalising an unacceptably low regulatory standard for the arms trade that could end up legitimising irresponsible transfers and giving legal protection to those selling weapons, thereby fuelling conflict and instability.

While a treaty with broad participation is, of course, desirable, UNA-UK strongly feels that a robust treaty – even if not all states are willing to sign it in the short term – will prove far more effective in the long run than a universal treaty to which all states can subscribe and subsequently ignore.