The United Nations recently approved its budget for peacekeeping for 2018-19 as well as a slew of longer-term reform proposals.

Fred Carver, Head of Policy, wrote an article about this originally published by the International Peace Institute Global Observatory blog on 14 September 2018. You can read that here.

The article presented more information on the UN Peacekeeping budget, and we reproduce that, with some additional detail, below:

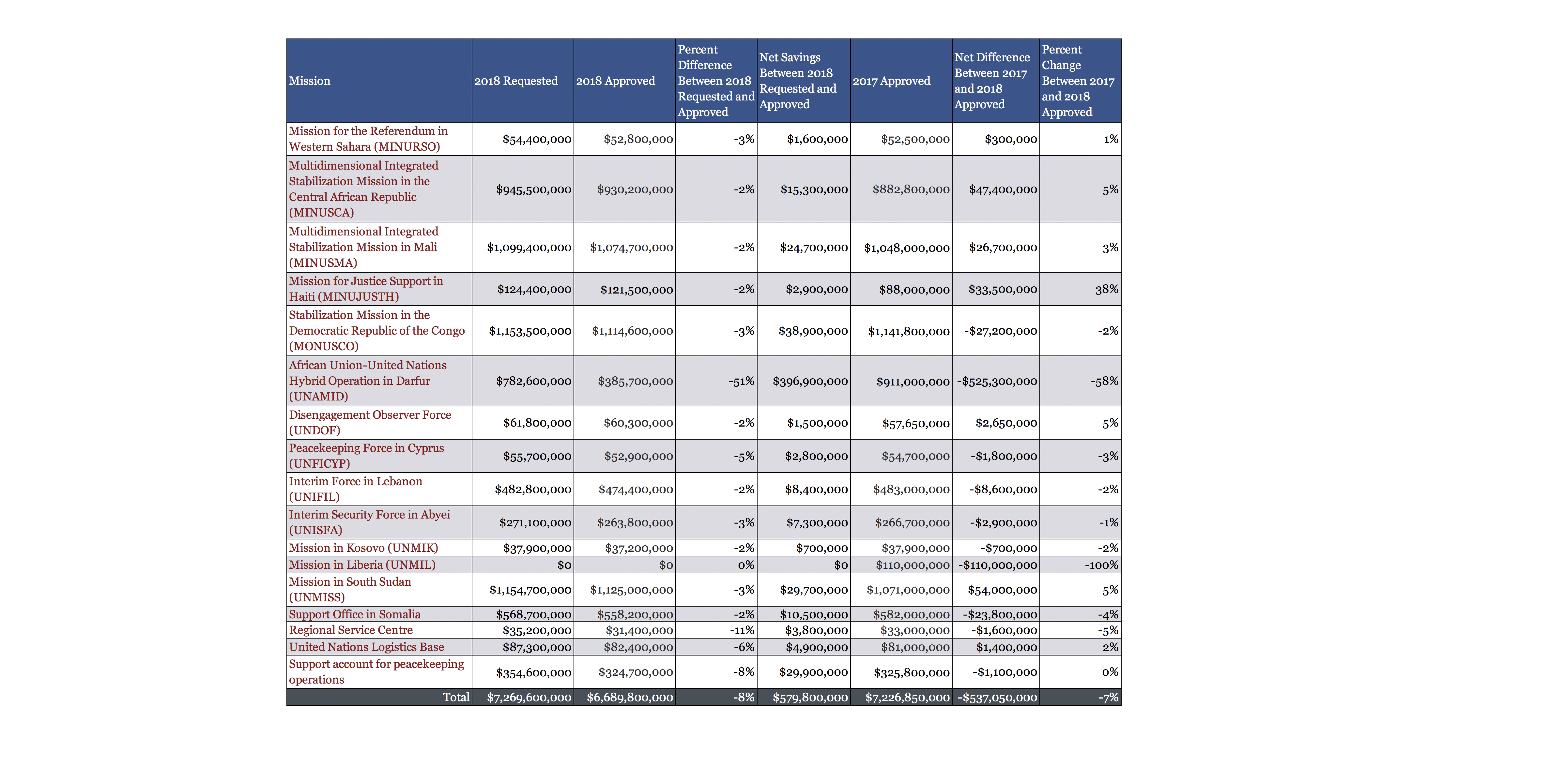

2017 and 2018 Peacekeeping Budget Comparison

Note: the budget for UNAMID only covers the first six months. Further funds will be approved in December and will alter these figures.

The Trump administration came into office pledging to cut peacekeeping by over $1 billion—an arbitrary figure with an absence of clarity as to whether it refers to the total budget or only the US’ share. The US claimed a $600 million cut last year to the total budget contribution to peacekeeping—about which the US ambassador to the UN said “we’re only getting started.” This latest round of cuts nudges the cumulative total closer to that $1 billion target, but still not over it. The US looks set to negotiate strenuously to reduce the percentage of the total it pays during the triannual review of scales of assessment which will start in October (and in the meantime is going into arrears in dispute over its contribution, as the US will owe the UN $500 million by January 2019, causing a hole in the peacekeeping budget of at least that size) and it may well be that if the US is paying a smaller proportion of the budget their enthusiasm for cutting it will be sated. But the fear is with a fresh US electoral cycle starting shortly there will be a renewed demand for nine and ten figure cuts.

Few would argue that UN peacekeeping operates with maximal efficiency or that reform isn’t needed—although delopying UN peacekeepers continues to be eight times cheaper than a hypothetical deployment of US troops to the same location—but there is very little that can be safely cut. The end of the UN mission in Liberia saved $110 million, which is likely to account for over half of the UN’s savings this year.

Smaller missions have been consistently cut year on year by around 5 percent and are probably at the limit of what can be cut without compromising performance. In any case, further cuts would not save that much money: the UN’s four smallest missions, their Regional Service Centre, and their Logistics Base, only cost $317 million all together.

The US has been pushing for the closure of one of these missions—the UN Mission in Western Sahara (MINURSO)—which would save around $53 million. However, the consequences for the unsteady ceasefire in the Western Sahara are unclear, so the mission will continue for another year with a very slight budget increase. Converting the UN mission in Haiti to a purely policing presence did save a significant sum of money last year, but costs are already rising again with this year’s budget request containing a near 40 percent increase to $121 million. The only other mission which looks likely to be wound down soon is UNAMID, and that is a process fraught with danger.

The Big Four

That leaves us with the “big four” missions, the UN’s near-billion or billion dollar missions with troop numbers in the tens of thousands: MINUSCA (Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic), MINUSMA (Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali), MONUSCO (Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and UNMISS (Mission in South Sudan). As UN veteran Ian Martin said (during his keynote address to the conference UNA-UK jointly convened with the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in May) all four are facing grave difficulties as the peace the missions were sent to keep disintegrates further.

Compared to 2017 (see table above), MINUSCA was given an extra $47 million in this year’s budget although they had requested $63 million, MINUSMA an extra $27 million despite requesting $51 million, and UNMISS an extra $54 million of a requested $84 million. Given all three missions are tasked with maintaining order in contexts where peace processes are under strain or unravelling, the money will doubtless be necessary to support expanded operations. It may not be enough or as much as requested, but funding increases of this size are likely to prove the exception rather than the rule under the current US administration.

As for MONUSCO, the UN requested a $12 million budget increase but instead received a $27 million budget cut. This might not be a significant sum in the context of the overall peacekeeping budget, or even MONUSCO’s being as it is only around 2 percent of the total, but so precarious are the finances of the mission that it could yet prove costly in the long term. This mission's budget was explored in a separate article for IPI, available here.

To find out more, you can read the full IPI article here.