The United Nations was for us a refuge… We could come here and people would listen to us and we would be understood. And that friendship, that comprehension, that support has been of the utmost importance to us*

The term “human rights” appears seven times in the UN Charter, making the promotion and protection of human rights a priority for the Organization. In 1948, it adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a “common standard” for all peoples and nations. The Declaration became the cornerstone of the international human rights regime, which today includes legally-binding treaties and monitoring mechanisms, an intergovernmental human rights forum, independent experts and a dedicated UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

In its first decades, governments were keen to portray human rights as domestic matters. As a result, the UN’s work was largely confined to standard-setting. The only situations that received widespread condemnation were South Africa and Israel-Palestine. It was not until the 1973 coup in Chile and its bloody aftermath that the UN began to pursue human rights violations more aggressively, through naming and shaming and on-site investigations, for example.

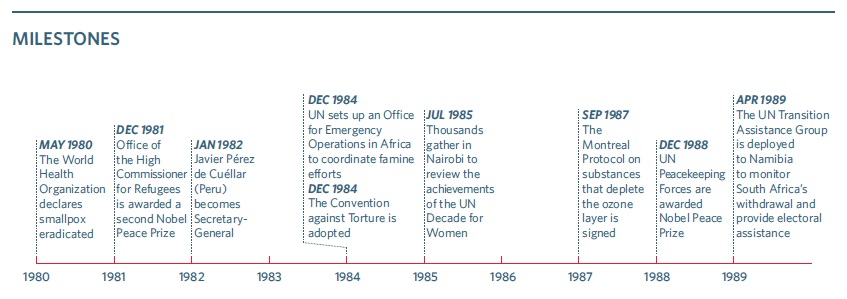

In the 1980s, this work expanded massively, with an increasing number of countries subjected to increasingly intrusive procedures. In February 1980, the UN established the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, the first such body to have a universal mandate. In December 1984, the Convention against Torture was adopted, the first human rights treaty to apply the principle of universal jurisdiction. And in November 1989, the Convention on the Rights of the Child was agreed, the first legally-binding instrument to encompass the whole spectrum of human rights – civil, political, economic, social and cultural.

The UN also began to involve NGOs and victims more systematically in its human rights work. Estela de Carlotto, head of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, is one such campaigner.

Her grandson was born in 1978 during her daughter’s detention by Argentina’s military dictatorship. She was informed that her daughter had been killed but the fate of her grandson was not revealed. An estimated 500 children disappeared during the “dirty war” – part of a systematic plan to pass the children to allies of the regime to prevent the raising of another generation of “subversives”.

The Grandmothers group was founded in 1977. They continue to search tirelessly for their missing grandchildren and have now found over 100. Estela’s own grandson was finally located in 2014. Speaking at the UN later that year, she thanked the Organization for standing with the Grandmothers for over 30 years, and for walking with them as they moved from a group of inexperienced laywomen to a sophisticated NGO that provides legal and psychological assistance to victims of enforced disappearances.

*Estela de Carlotto, head of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, speaking at the UN in 2014

Photo: Abuelas (Grandmothers) de Plaza de Mayo. Copyright CC/AHLN