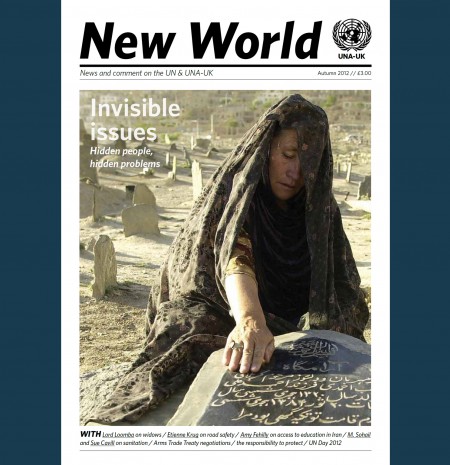

In 2010 and 2012 respectively, I undertook research in northern Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo on rape and sexual violence. Pregnancies resulting from rape, the stigmatisation suffered by the children subsequently born, sexual violence against males – these issues often get overlooked by policy-makers and the press.

The 76 young women I interviewed in Goma, eastern Congo, demonstrated the prevalence of sexual violence and that the rape of girls under eighteen by community members is widespread. The experience of rape results in extreme social rejection by families and communities, even more so if a child is conceived. Girls gave tragic accounts of being harassed, thrown out of their homes and schools and being forced to flee to insecure accommodation, where they are vulnerable to further abuse. The psychological effects are also debilitating, including depression and suicide attempts. The impact also extends to the children conceived from rape, who are mistreated and considered ‘dangerous’ within communities, increasing the likelihood of further violence.

Survivors experience serious reproductive health problems including sexually transmitted diseases, HIV infection, AIDS and fistula (where rape causes a tear between the vagina and anus resulting in leaking of urine and faeces). If they become pregnant, they have few options (abortion is illegal) and often experience complications during birth as a result of their injuries. The poorly-resourced state health system struggles to respond to survivors’ needs and free treatment is available only for those who can prove rape. Security threats make the work of organisations providing such services dangerous. Survivors see little to be gained from reporting rape in a culture of sexual exploitation and impunity, where rape has become ‘normal’. The police and judiciary suffer from a gross lack of funding and struggle with overwhelming logistical problems. This absence of adequate services reinforces the prevalent view that survivors have little value in society.

Although rarely reported, sexual violence against men carries high levels of stigma, particularly in countries where homosexuality is illegal. Despite the serious physical and mental health effects, local cultures inhibit disclosure and service access. Male rape is viewed as an ‘abomination’ with survivors being ‘cast out’. Men who are raped are considered ‘women or lower than women’. Wives of raped men are not respected within communities and their children are also stigmatised.

Such sexual violence can transform a whole community, with lasting impacts even after conflict subsides. The socio-economic, physical and mental health effects, coupled with social exclusion, have profound effects on people’s identities, relationships and capacities. Men who are raped experience particularly high levels of stigma, causing them to leave their villages – unable to find work, they become destitute.

Urgent action needs to be taken to improve gaps in the humanitarian response:

- Donor funding is required to increase access to physical and mental health services for both men and women. A holistic approach is required, encompassing access to medication preventing HIV infection, emergency contraception and safe abortions within the required timeframe, as well as parenting skills programmes

- Economic empowerment schemes, education and support groups would help tackle stigma and psychological trauma. Community programmes should encourage acceptance of survivors and their children

- Training and support for professionals and service providers would help share best practices and prevent the ‘burn out’ of these individuals

- Boys and men should be fully involved in community programmes that promote gender sensitivity, attitude change and role models of non-violent men. They can serve as active agents in protecting others from abuse and breaking down the culture of sexual violence

- More women are needed in the police and justice systems to advocate for the rights of survivors and their families

- Rape is experienced simultaneously as a violation of the survivor’s body and rights. There is real value in promoting greater communication between health and justice services

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to all in Goma and Bweremana, eastern Congo and Kitgum, northern Uganda who generously gave their time and for the knowledge they shared. Appreciation also for the assistance of The Institute of Mental Health, Goma, and Kitgum Women’s Peace Initiative, KIWEPI, Kitgum, and Isis-WICCE, Uganda for translation and facilitation.

Dr Helen Liebling, a Lecturer-Practitioner in Clinical Psychology at Coventry University and Coventry & Warwickshire Partnership Trust, has been carrying out research with survivors of conflict violence and torture in Africa since 1998. She was recently invited by UN Women, WHO and Sexual Violence Research Initiative, MRC, to plan a 5-year international research agenda on sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict settings.